Ex Libris: An Atlas of Es Devlin

0 min read

Jonah Freud dives into the universe of artist Es Devlin via her new book

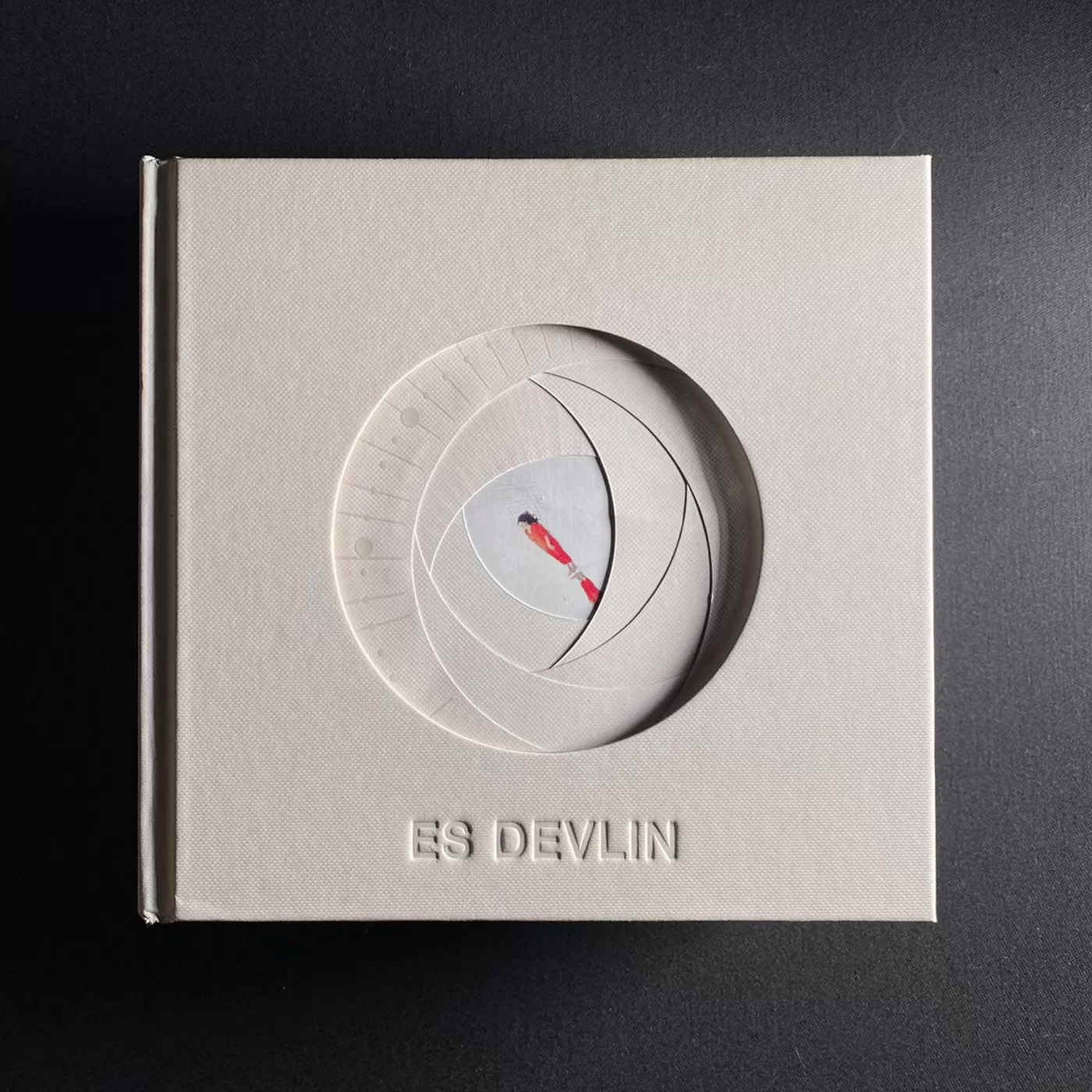

Detail from An Atlas of Es Devlin, Thames & Hudson

I read very little contemporary fiction, and collect very little contemporary art. My shelves at home have a bad showing of 21st-century writers and artists, and the shelves at Reference Point, though better, are dominated by the world of post-war creators. It’s not because old things are superior, or that there aren’t great things being made in the contemporary age, but rather the simple fact that time is one of the great curators. Decades are good at trimming the fat, and though nothing is meritocratic, most things of worth will stand the test of time fairly well. All of which is to say, when something comes across my desk that was printed this year, there is a small dose of scepticism. And when I see something made this year that feels like it will rank in the pantheon of great works, I have to stop myself and re-evaluate. Yet re-evaluate I have, making sure my critical eye is not altered by the bias of my personality, and here I am writing this column telling you that An Atlas of Es Devlin, launched mere weeks ago, might just be one of the great artist books of the century.

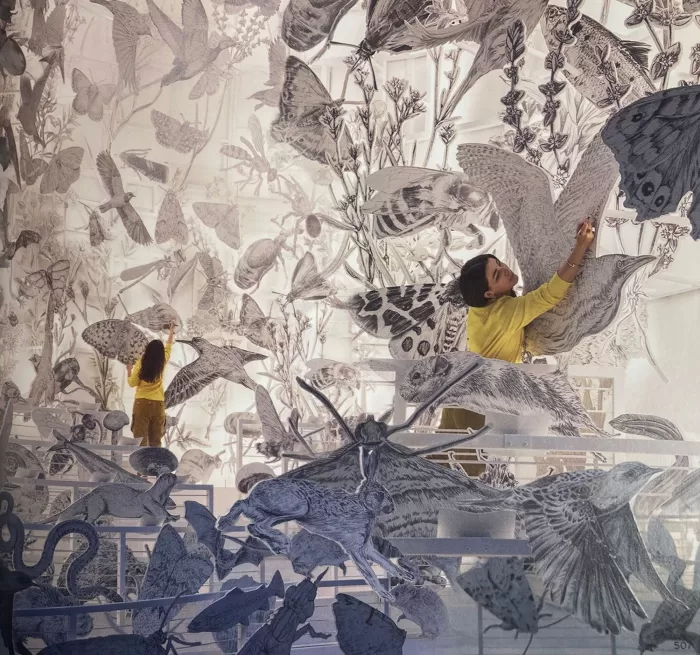

This should come as no surprise to those familiar with Devlin’s work. An undisputed, perhaps the undisputed, genius of her craft, Devlin is a set, stage and theatre designer and, above all else, an artist in the truest sense. If you didn’t know that already, one look through An Atlas will affirm it for you. A die-cut cover leads you down the rabbit hole and deep into her mind, beginning with teenage sketches and covering the wealth of projects between then and now, which include public art installations for major museums, stage designs for the likes of Beyoncé, Jay Z and U2, and sets for the most prestigious theatres on the planet. But the book hides secrets that belie its appearance. You quickly realise this is not a celebration of finished work but a declaration of process, of the unfinished and unrealised, the messy and hastily sketched. Accordion foldouts and staple-bound zines emerge from the pages like mushrooms growing out of a forest floor, translucencies reveal and remove and the work seems to transform across the pages.

From a design perspective, this 700-page tome is an extraordinary feat. From an artistic point of view, it is little short of a masterpiece. Perhaps the great pleasure, as is often the case in retrospective works such as this, is finding the threads in her work that start at 16 and carry through to adulthood. The mediums, contents and requirements change but obsessions, fascinations and personality remain. Clearest above all of these, is a unique type of world-building. Devlin doesn’t fall into cliche because she understands worlds in an intense and personal way, in fact she understands the world as a personal, living entity. It’s clear, in An Atlas, that it all begins and ends with this. Devlin is able to understand the micro and the macro as singular and communicates this in the medium of high pop – Gaia Theory brought to life at a Beyoncé concert. Bodies in space and space as bodies, An Atlas plays with scale just the same as her largest works, it zooms in and out with a generous hand guiding you through like Charles and Ray Eames in their documentary The Powers of Ten. And yet you never feel totally firm on the ground, just as the book starts to fall into a rhythm, a new design touch or conceptual idea emerges and your perspective has to shift, ever so slightly.

We have had the immense privilege of hosting Devlin at Reference Point for a talk, a privilege happening again later this year. Before she began speaking, she assessed the room, the way an artist looks at work in a gallery so different from a critic or punter. Her first order of business was to get herself and her fellow speakers to stand up and stay standing for the entire hour that they spoke. No consideration was given to whether that would be an enjoyable way to conduct a talk for herself, but rather she was surefire it would be a finer experience for the audience, their sight lines vastly improved. There were endlessly interesting ideas explored that night, but this small moment, instinctual, selfless and, to her, totally obvious, is something present in all of her work, and with the book. She considers her audience first. Unlike many painters, sculptors or photographers who often see their works’ purpose as sovereign, Devlin sees her work as serving an audience. She considers the individual experience in a unique and strange way. Go to any show designed by her and that is obvious, but to see it applied to a book is a truly exciting experience.

Artists’ books are often artworks just for the sake of it. These are beautiful things. The book becomes a canvas, a medium, to express something and the flourishes and playfulness within them are often just that, flourishes and plays. In An Atlas, the flourishes and the games serve a greater purpose. The reader is considered to an almost obsessive extent and she uses damn near every weapon in the bookmaking arsenal to make sure that experience is the one she planned. Nothing is superfluous. There are no gimmicks or cheap tricks. Nothing is for the sake of itself. It is a deeply generous work, but of course, it is – Es Devlin is a deeply generous person to all she encounters, even if only through the printed page.

Discover An Atlas of Es Devlin and many more books at Reference Point. reference-point.uk