How Málaga made Joel Meyerowitz

12 min read

In an interview with Plaster, the American photographer recalls his year-long European road trip in 1966, and how capturing the streets of Málaga made him the man he is today

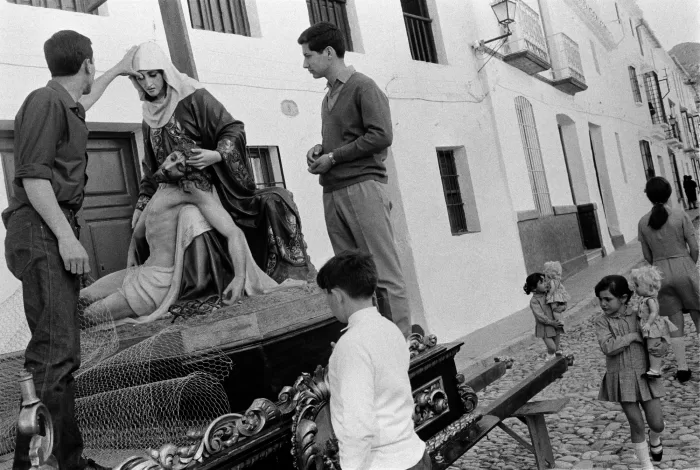

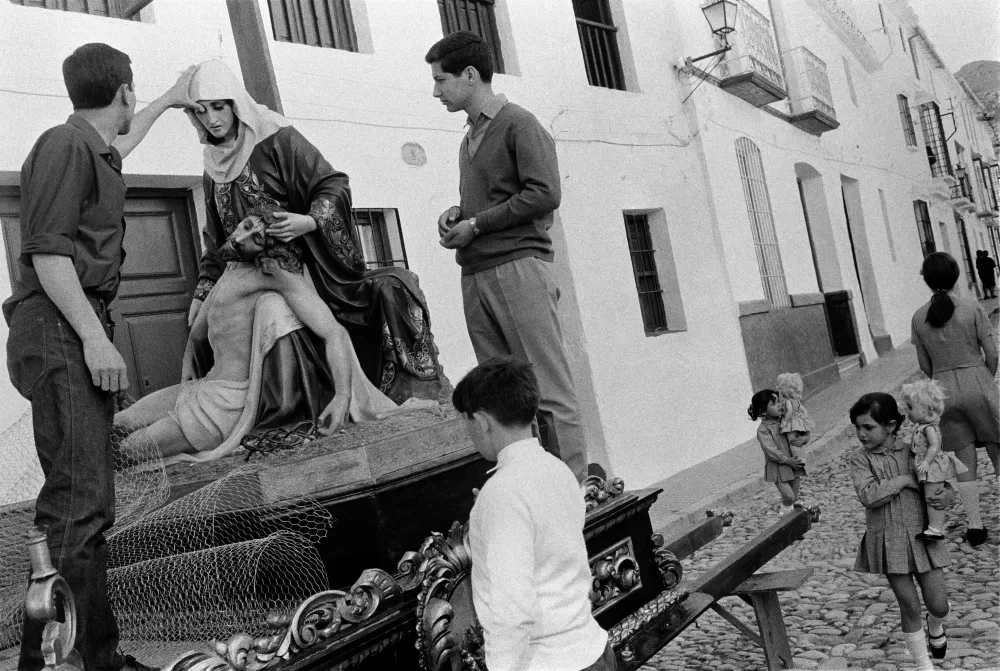

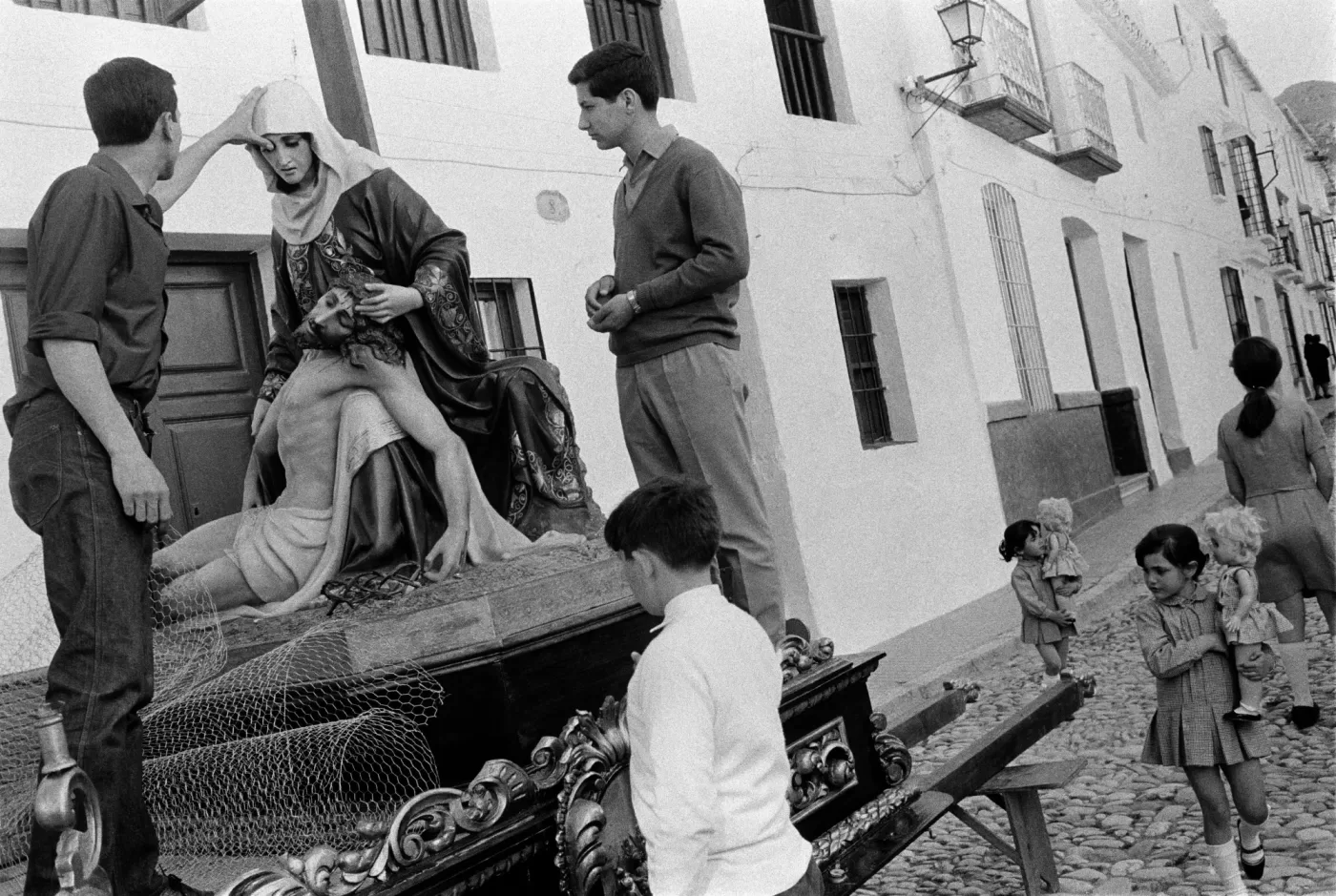

Joel Meyerowitz, Escalona family and friends, Málaga, Spain, 1967. Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

Before photographer Joel Meyerowitz shot Ground Zero, before he shot the beaches of Provincetown, he shot Europe. In 1966 he was 28 and had just made a decent wedge on an advertising job. “Everybody was saying ‘stay, make your career’,” he tells me, “and I thought fuck that. I’ve got money in my hand now, I just wanna live as an artist!” He and his wife Vivian set out on a European road trip: one year, ten countries, 30,000 km. For six months of that year, the two lived in Málaga, Spain, with the Escalonas, a gypsy family he’d been introduced to and from whom he learned to appreciate flamenco. This trip was the turning point of his life: it made him the man he is today, and the photographs he made won him his first solo exhibition, at MoMA. Now, he’s back in Magala, showing those early photographs at the city’s Picasso Museum.

I’m sitting with Meyerowitz in the museum’s garden. We’d actually met the previous day when he’d led a tour of the exhibition before a dinner and flamenco performance at a local restaurant. It’s been an “intense few days” for the 84-year-old photographer, but he’s feeling fresh. He’s seen a lot in life, and I get the sense he’s a little philosophical. I want to use this time to hear about the kind of man he was, how he changed, and if he can share a little life advice. What was driving him when he stepped onto the shores of Europe?

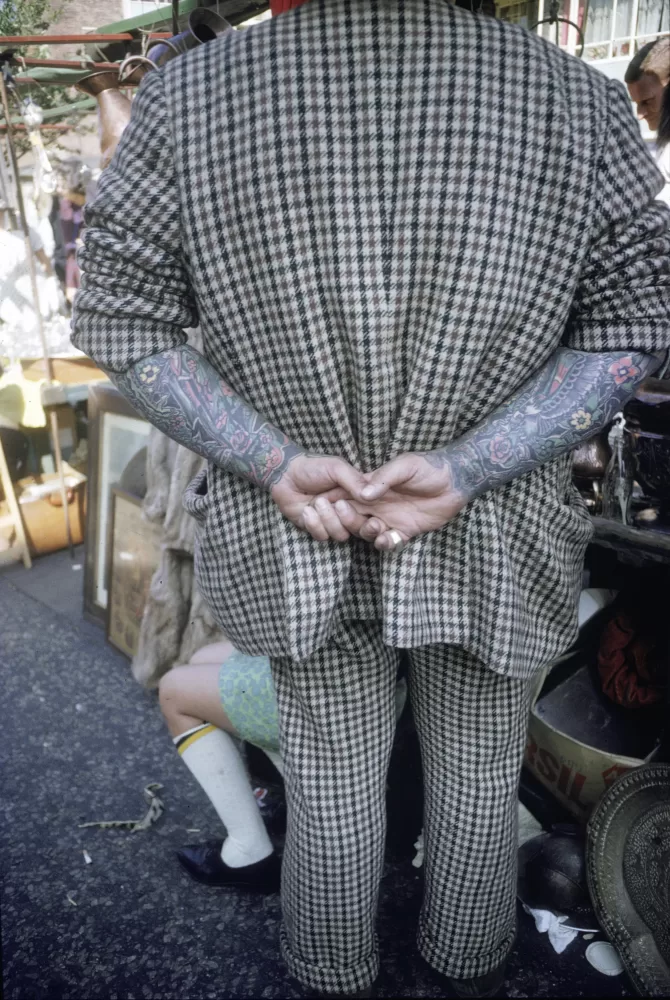

Joel Meyerowitz, 'London, England, 1966' Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz, 'London, England, 1966' Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

“I was wide awake and hungry, and I’d only been four years into photography, so my lust for the medium, my curiosity, my passion for it was just coming into focus. For the first two, three or four years one searches for one’s path. You try this, you try that, you don’t know or feel sure about anything, you just know that the momentum to go forward is like the wind at your back. And I think youth is all about that. And the more experiences you have, the more your focus on who you are, as you enter these experiences, is clarified. Coming to Europe, for me, was the first step in the clarification.”

“The trip, as an idea, was always about the mythology of art,” he says. Europe was where artists throughout history, from the Renaissance to the post-war years, have trained and discovered themselves. There was also a personal element to the trip: he was a “a kid from the Bronx” whose neighbourhood was almost entirely European immigrants. His own parents were Jewish immigrants from Hungary and Russia. Europe was life, in his words. He started in England. However, he found the people cold, unwelcoming and suspicious. He continued on to Ireland, much more friendly, then Scotland then France.

As the year passed and the weather grew colder, he made his way south, ending up in Málaga, Spain. It was different here, the country was deep in the Franco dictatorship, but even under this pressure, he found a certain freedom as an outsider. In the morning, he walked between cafes, drinking a little coffee and a little aguardiente. At night, he listened to flamenco and recorded the music and the people on tape and 35mm film. “I’m a total romantic,” he says, “in the best sense of the Romantic tradition, which is to go out into the world, to see the meaning of the world, and to see the old world, which is a world in which history and time have caused decay. I think that part of the Romantic tradition – to set yourself loose – is the dream of every young artist, maybe every young person.”

Joel Meyerowitz, Paris, France, 1967. Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

He made many of his photographs on the road, shooting from one of the front seats of the car, depending on whether he or Vivian were driving. He talks, with serious enthusiasm, about working on the move. “Being in the car was like being inside a camera. If you’re sitting at the wheel with the window in front of you, everything you’re seeing is in frame.” He makes a square with his hands. “When you’re in a car and you’re driving along and someone says lookatthat! and you turn your head, it’s gone already. But you saw something of moment; a gesture, somebody in a field scything or pulling something, or a man and an animal struggling, some little action or gesture would be enough to call your attention. But you’re going at 60 miles per hour, it doesn’t wait for you. I think that the risk factor, that it’s flying by you, the sense of seeing it from within the moving camera itself, is a concept that is thrilling, exciting, challenging. You want to test the system, you want to push against the system.” He punches his fist into his hand. “You mould it to your needs. That’s what youth is.”

It wasn’t always so easy. He admits that when he started, he was totally clueless. “I didn’t know what my subject matter was, I didn’t know who I was, I didn’t even know how to make the pictures but I started to figure it out, because that’s what you do, you figure things out.” He tells me about using his skills as an athlete and a dancer to move between people, and he recalls watching Henri Cartier-Bresson talk people into taking their pictures, “he was a charming, good-looking son-of-a-bitch. He could move through anything!”

He talks about learning to read the ‘text’ of the street, “You see something interesting happening over there, 30 feet away,” he points, “and you’re moving this way,” he slices his hand at a right angle, “and something is coming here,” he waves behind his head, “you try to anticipate where these things might play out.” It’s all about being aware of your place in the world, and how the world is affecting you. It’s all about building trust in yourself. “You begin to trust that you have that authority over your own recognition and behaviour, so you try to shape that, and then that leads you to a different state of understanding and anticipation.”

Being in the car was like being inside a camera. If you're sitting at the wheel with the window in front of you, everything you're seeing is in frame.

Being in the car was like being inside a camera. If you're sitting at the wheel with the window in front of you, everything you're seeing is in frame.

Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz, 'Málaga, Spain, 1967'. Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz, 'Málaga, Spain, 1967'. Courtesy of the artist © Joel Meyerowitz

As his skills developed, so did his understanding of what he was doing. “I think it’s rare to have your own original thoughts until you’re in your mid-late twenties.” He declares. “Before that, it’s all book learning or observations, things like that, but when you put it into practice and it pays off, you can do it again and again and again. Really, coming to Europe, I began to have my own original thoughts. I was no longer hanging out with Tony Ray-Jones or Garry Winogrand or Tod Papageorge, I was a singular entity living in a foreign country, where the language, behaviours and the dictatorship all had a kind of pressure. One has to go deep inside to understand who you are in this environment, and how you make work. That’s the great game of life.”

I ask him, was there ever a single pivotal moment, like a snap of the shutter, which changed him? He stabs his finger down on the table. “Right here in Málaga.” Meyerowitz recalls bumping into a fellow flamenco aficionado, Pepe, one day. Pepe decided on the spot to ditch work for the day and join him on a wander. “Don’t you have to go back to the office?” he asked. “Yeah, but I’d rather be with you!” Pepe said. Then Pepe delivered the line that has stuck with him ever since: “You have to learn as a young man to spend yourself freely.” He snaps back in his chair. “That was like shooting an arrow into my head. Spend… yourself… freely.” He emphasises each word. “Just do whatever the fuck you want! I thought, ‘of course, that’s what I’m doing! I ran away from New York!’ and he had somehow compressed it into a philosophy in just a few words. And I have lived my life that way ever since… because that’s all you have in your life; what you make of it. Otherwise, you’re gonna grow old and say ‘if only I’d done this or that,’ I don’t have any regrets!”

At that moment, we spot the museum’s press officers standing anxiously in the corner of the garden. He’s due at a press conference and we’re running a little over time. “Don’t look, don’t rush” he whispers. They try to drag him away, but he waves them off. “We’re really in something good, so I want to give him everything.” He turns to me, “we’ll just do what we wanna do!”

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

Everything we’ve been talking about was 60 years ago, essentially a lifetime. Does he even recognise the photographer who took those images? “Those were made by the flowering of my youthful appetite, and now here at 86 I’ve been through a lot of changes in my life.” He takes a moment. “I do feel a genuine connection to the person who made those pictures. I can see in myself the humour, the poignancy and tenderness, the bittersweet quality of seeing life with its tragedies and its joys. All of that emotional humanity. I think of myself as a humanist. My pictures are not about contrived visual scenography, they’re about these moments that are happening and disappearing in the very same second. And my tuning of my instrument, which is me and my camera, to try to be in the right place at the right time, I see it in those pictures.”

He talks of every photograph he takes as a physical manifestation of a moment in which he was moved. That’s the real connection. “I think of it like being stabbed with an instantaneous recognition of emotion and meaning, because life is flowing by all the time, and only occasionally do we recognise a moment of meaning – something that calls us, you pay attention to it and you look at it hard and you think ‘wow, that’s something.’” That ‘something’ is difficult to define, but he still feels it and still sees it in several of his photographs in the show. “The way a man at a cafe table reaches across to the woman he’s with and holds her face with his hands; or the struggle, like getting that horse up on that cart, the human dynamic and the engineering of that; or seeing that man walking down the street with his hands in his belt and he’s hunched over and there’s a guy behind him and two boys on the ground, playing. What the fuck is that all about?! But I love that! To me, the ambiguity of that is where the meaning lies, because life is rich in ambiguity. To describe ambiguity in a photograph is a risk, because it’s either nothing or it’s something.”

Joel Meyerowitz, Greece, 1967 (MoMA title: Greece. Rt. E87, near Trokala). Joel Meyerowitz Archive, New York © Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz: Europe 1966-1967 is on view at Málaga’s Picasso Museum until 15th December 2024. museopicassomalaga.org