Orlando Whitfield sets the story straight on Inigo Philbrick

12 min read

The art dealer turned author talks to Jacob Wilson about his new book, All That Glitters, which lays out the dramatic rise and fall of his former friend and business partner Inigo Philbrick

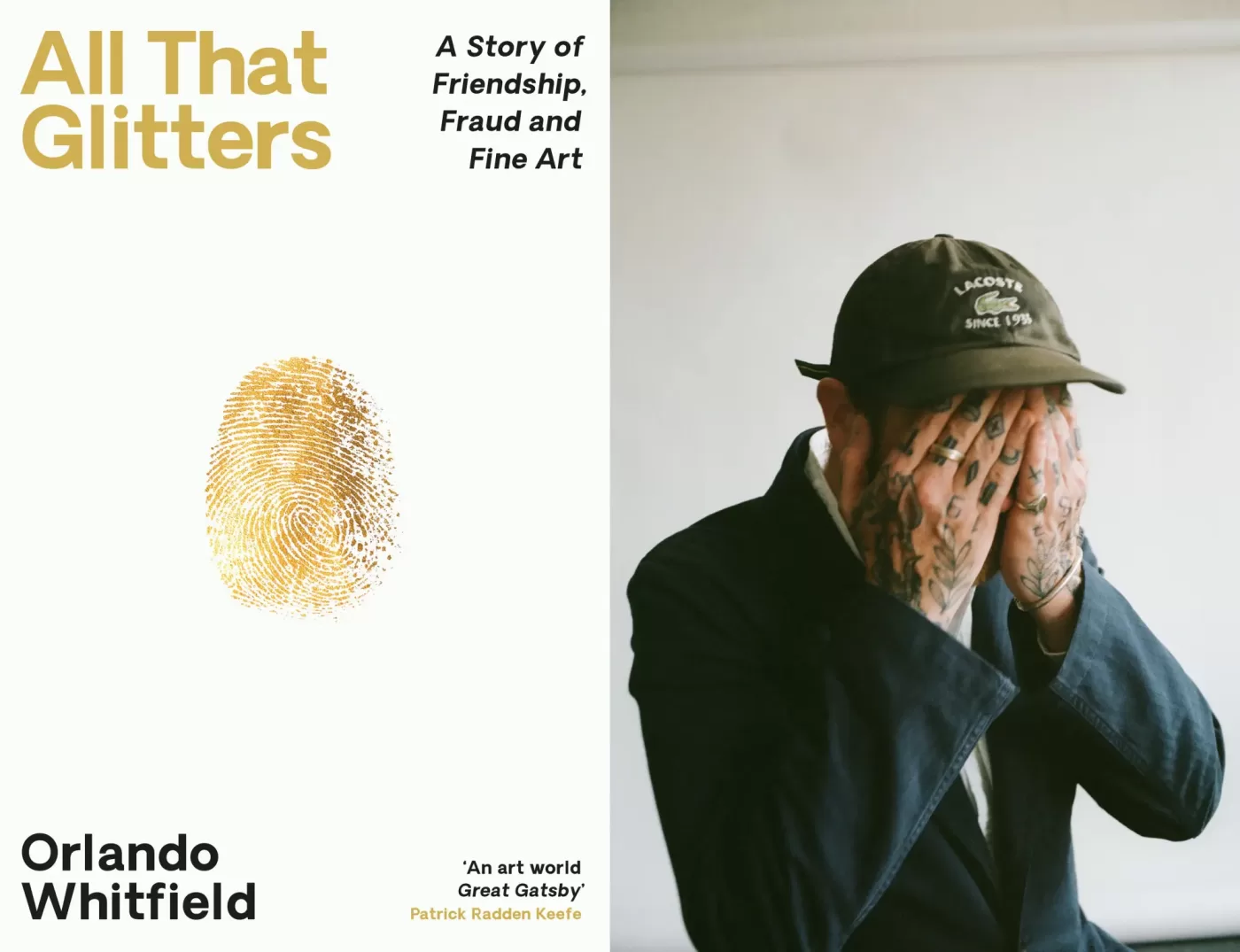

Orlando Whitfield. Photo: Gabby Laurent. Courtesy Profile Books.

You think you know the story of Inigo Philbrick; the awkward, intelligent art history student, turned prodigy dealer, turned convicted criminal of an $86M wire fraud, who sold shares in paintings he didn’t own, took out loans on artworks he didn’t own outright and forged sales records, earning him the nickname “Mini Madoff.” When Philbrick pled guilty at his US trial in 2021, he was asked by the judge why he committed the crimes, and he offered an apparently honest and shockingly simple motive: “Money, your honour. I was trying to find business and I needed money for that.” Now that Philbrick is out of prison, having served four years of a seven-year sentence, people are asking if the story really is that simple.

Orlando Whitfield sets the record straight in his new book, All That Glitters. Whitfield was a friend to Philbrick from their student days at Goldsmiths in the late 2000s; he was Philbrick’s first business partner and worked with him on some of the earliest dodgy deals (the pair tried to sell a Banksy on a building they didn’t own); they remained friends as Whitfield started his own gallery and Philbrick rose and fell through the ranks of the London art world; they even stayed in touch while Philbrick was hiding out in Vanuatu, on the run from the US courts. If anyone’s going to be able to tie up the loose ends in this case, it’s Whitfield. But, as Whitfield tells me when we met earlier this year to talk about his book, the problems are bigger than one man. All That Glitters describes an industry in which the pressure to keep up drives people to either burn up or give up – Philbrick chose the former, Whitfield chose the latter.

To most in the art world, Inigo Philbrick is simply a name in the papers, to some he’s a former peer turned scammer. I ask Whitfield what he saw in Philbrick, and his answer is simple. “A friend. I saw him as a friend.” He describes his art education as “going to galleries with people who knew more than me and asking questions,” and recalls with a degree of fondness that most of that time was with Philbrick. “God, did he know his stuff – and I was proud to work for him, for that reason. He knew his stuff better than any auction house specialist I’ve ever encountered. He loved art, and it’s just deeply sad that his association with art and the art world will forever be this calamity.” And how does he see Philbrick now? “I don’t really know. I feel rather sorry for him because he screwed up his entire life. He had an enormous amount of promise and it’s very sad that he’s ended up where he’s ended up. He’s hurt a lot of people and he’s ruined what would almost certainly have been a glittering career. It’s a shame.” I ask Whitfield if he thinks Inigo has changed in the time since he last saw him, but he shuts me down. “These are questions to be addressed to Inigo, I can’t speak to his mind.”

Yeah sure, the guy ripped off a lot of people, hurt a lot of people, fucked over a lot of lives. But he was also funny, he could be generous, and sometimes that generosity was probably quite genuine.

Yeah sure, the guy ripped off a lot of people, hurt a lot of people, fucked over a lot of lives. But he was also funny, he could be generous, and sometimes that generosity was probably quite genuine.

Okay. So, why write this book? Whitfield outlines two basic reasons. First, there are the matters that are close to his experience. His dissatisfaction with the media coverage of Philbrick’s case. “I was quite shocked by the media coverage.” He says. “It makes me worried quite how readily newspapers of record were happy to print things which clearly had not been fact checked; because they were not factual.” He’s particularly annoyed by the one-dimensional character of Philbrick created by the media. “I wanted to put across a side of Inigo that was not just this cold, dead, Tom Ripley demon which had been painted. I mean, yeah sure, the guy ripped off a lot of people, hurt a lot of people, fucked over a lot of lives. But he was also funny, he could be generous, and sometimes that generosity was probably quite genuine.”

Second, there are larger, impersonal issues that Whitfield wants to address. “His case was interesting in many ways,” he says, “but actually it was more what the case shows about how the art world works. The way in which Inigo was able to exploit the gentleman’s agreement; the idea that pictures are bought and sold on a handshake over a thousand pounds worth of champagne. That was the thing I was interested in exposing by writing about Inigo’s story; his is exemplary of the utter lack of regulation in the art market.” All That Glitters describes an art market that is so opaque that even the insiders, let alone outsiders, aren’t fully aware of what’s going on and how others’ businesses work. “What I really wanted to do was to show the art world in the same way that Michael Lewis did for the bond market in Liar’s Poker.” He says, referring to the unflattering, semi-autobiographical 1982 book that exposed the brutish ‘big swinging dick’ culture on Wall Street.

To do so, Whitfield drew on his own experiences. But he was helped by a significant and surprising gift from Philbrick, a folder of evidence; thousands of emails and documents that together described his entire business. I ask Whitfield how he felt when he opened that cache. “It felt extraordinarily voyeuristic. Especially because some of it allowed me to fill in gaps and to answer questions I had had while working for Inigo.” Another source was Philbrick himself, who sent sporadic text messages from his Vanuatu hideout. “I had a huge number of questions about the documents that Inigo had sent me which I was never able to get answers to. There are stories he’d never quite finish because he was late to dinner and, ‘oh sorry, we’ll finish this story tomorrow,’ and then tomorrow never happened. He was incredibly good at being amazingly unavailable.” He tells me that the book went through several drafts, and that under the guidance of his editor Cecily Gayford he learned to be honest about his ignorance. Thanks to this approach, there were only a handful of anecdotes that were left on the floor of the lawyer’s chambers.

It’s commerce dressed up as culture. It has a veneer of civility, but actually it's just money.

It’s commerce dressed up as culture. It has a veneer of civility, but actually it's just money.

Whitfield’s account does a good job of breaking down the popular understanding of the art market as a genteel, intellectual space. In Whitfield’s view, it’s simply “lies, one upmanship and trophy touting.” This public boasting and conspicuous consumption is matched by the discretion, bordering on secrecy that underlies every deal: paintings are bought with handshakes over dinner, there are few written records, and to save face, nobody admits to a broken deal. In a bitter putdown, he dismisses it as “commerce dressed up as culture. It has a veneer of civility, but actually it’s just money.”

It’s a fact of the art market that you are always dealing with people richer than yourself. The friction of these interactions still burns Whitfield. “I come from a relatively privileged background and I worked in the art world and was able to sustain a career in it for a few years.” He says. “But I was pushed face-up against the glass to the most extraordinary wealth and feckless privilege – and I mean really feckless – people for whom their money and their status are things to which they are entirely oblivious. The attitude of these people is one of complete almost wilful ignorance sometimes.”

You have to remember that you’re hoping to do business with these people. You find yourself going along with things. Whitfield describes the part of the art market that he worked in as “a service industry” in which you have to be everything to everyone. “You are the friend to the person who wants to go clubbing with them, you’re the museum guide to the person who wants you to take them round the Tate, and I think that can become pretty grinding.” He notes that given most deals fall through, most of this work will be for nothing. Some might write this off as a cost of doing business, just a red cell on a spreadsheet, but Whitfield emphasises the emotional impact. “It can become pretty disheartening when you’re putting in all that work and going home at two in the morning to sleep in your noisy, main-road flat in Peckham, knowing that the person you’ve failed to sell something to – something that would have made your year – they just don’t notice.”

In the middle of the book, Whitfield recalls his spiral into addiction and breakdown, induced in-part by his worsening relationship with his dying father, in part by the pressures of the art market. As he shares his deeply personal experiences with me, I begin to truly understand why some people desperate for fame, or money, or simply a comfortable life, facing failing deals, rising bills, and the growing fear of losing it all, are willing to take very big risks.

I think he thought he would land the trick. I think he thought that it would all be fine, and five years down the line everyone would have forgotten about the horrendous nightmare that was.

I think he thought he would land the trick. I think he thought that it would all be fine, and five years down the line everyone would have forgotten about the horrendous nightmare that was.

I have a few lingering questions about Philbrick that I hope Whitfield can answer. For instance, how did the fraud start? Was he simply out of his depth, or was it planned from the beginning? “Obviously there was a point at which he decided to break the law. He willingly and with full cognizance did what he did. But, he was on track to be the secondary market dealer of his generation, I don’t know why he would have thrown it all away.” He says, incredulously. “I think he thought he would land the trick. I think he thought that it would all be fine, and five years down the line everyone would have forgotten about the horrendous nightmare that was – and that would be that. I’m sure there are other dealers who have been in similarly difficult waters and have landed the trick.”

Is the art market the way it is because of people like Philbrick, or does the market force people to act unethically and even illegally? I put the question to Whitfield; was Philbrick a problem for the market or a product of his environment? “I think capitalism’s the problem, surely.” He says. “People are always going to take as much of anything as they can get, and in the art market it’s easier than in, say, the financial markets, because no one’s watching. No one really cares. There’s no oversight or regulation.” So, if it’s a lack of regulation in the market that causes this, how about we change how it works? What would Whitfield do? He replies by quoting Larry Gagosian, that trying to change the art market “is like asking Dante what he would change about the structure of hell.” He laughs. “If Larry doesn’t have an idea for it, I certainly fucking don’t.”

I get another laugh when I ask how it feels to finally be out of the art world. “I still love going to galleries, which was something I got sick of towards the end of working there. I’m pleased to have that back.” He admits that he’s still “completely addicted” to the gossip. He does have some good words to say about the industry; he also names several of his friends and peers with whom he’s still in touch – his former business partner Ben Hunter, Grace Schofield of Union Pacific, Dave Hoyland of Seventeen, and Will Jarvis, founder of Gertrude – as “nice, honest, good people.”

To me, it feels like despite his exit from the art world, his relationship with Inigo is unfinished. I ask whether he’s going to try and get in contact with Inigo. His response is emphatic. “Inigo severed contact with me. So, if he wants to get back in contact, I’m sure he will. But I suspect he will have far more important things, like getting back to his life: he has a daughter who he’s never met and a fiancée. If I were him, I would just want to get out and do all those cliched things that Morgan Freeman does at the end of Shawshank Redemption – have a beer, sit on a beach, god knows what you’d miss… real food, I suspect.” However, Whitfield does hope that Philbrick at least recognises his work. “I hope, at least, I’ve put across a better picture than anyone else probably would have been able to write, simply because I was there. I’m sure that other people could have written it better, line by line, but they wouldn’t have been able to do what I was able to do for Inigo’s story. I hope that whatever he thinks of the book, he’ll realise that that’s something which it does achieve.”

Orlando Whitfield. Photo: Robin Christian. Courtesy Profile Books.

All That Glitters: A Story of Friendship, Fraud and Fine Art is published by Profile Books