Is Marina Abramović’s new skincare range for real?

6 min read

Durex aesthetics, white bread and longevity influencers: Marina Abramović’s new skincare range leaves Elise Bell questioning whether it’s all a stunt

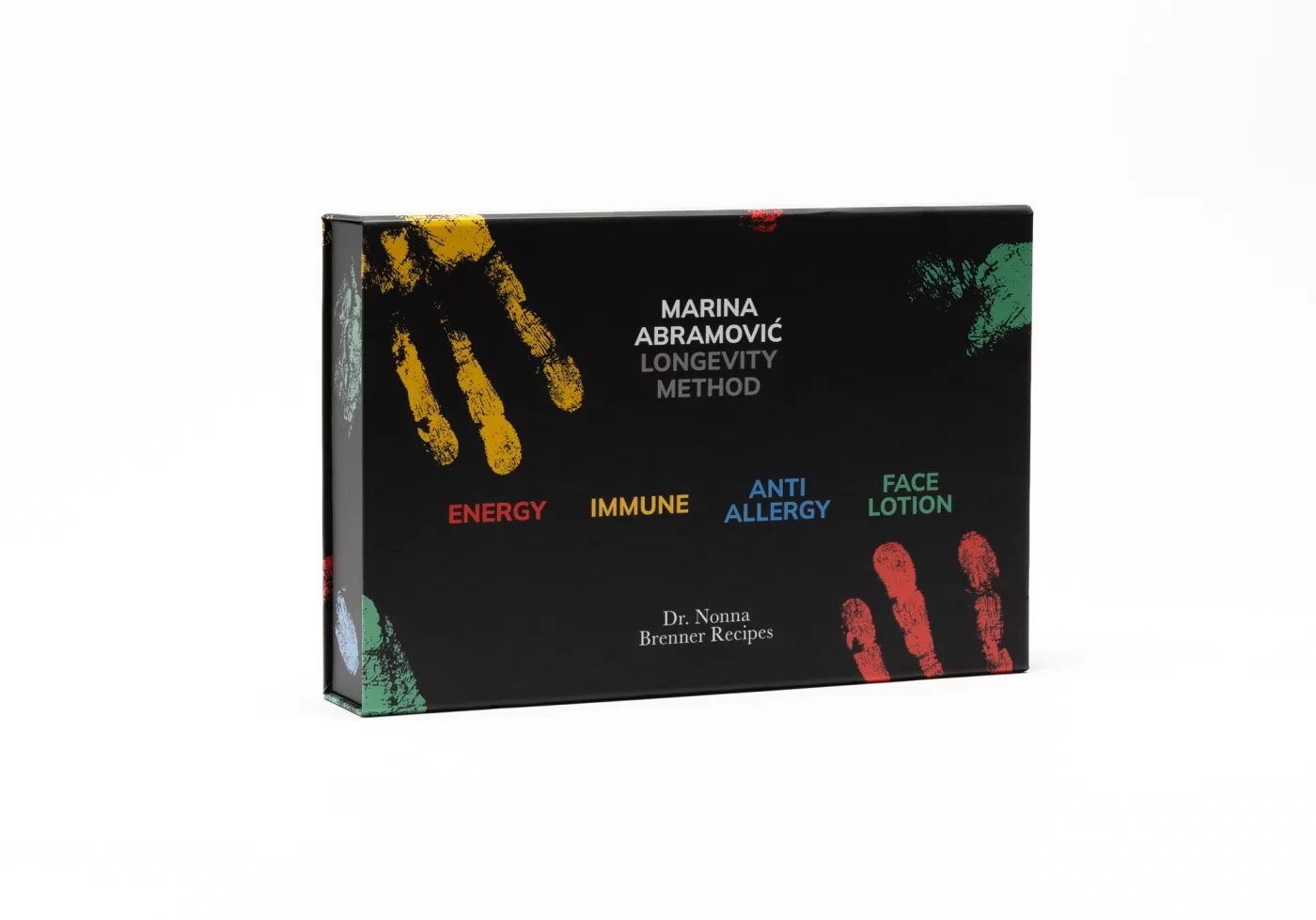

Marina Abramović Longevity Method collection (first edition) £459.00. Copyright Marina Abramović Longevity Method

I’ve never met Marina Abramović in real life. Instead, I’ve met her through a screen, a 30-minute interview overrunning into an hour as we spoke on issues including but not limited to: abusive mothers, artificial visions of reality, and the Serbian Orthodox Church. By the end of our allotted time, I had realised two things. One: that I could never be a performance artist. Two: that I could understand how people join cults.

The impact of Abramović on 20th-century art cannot be overestimated. Moving beyond the borders of Yugoslavia, by the 1980s Abramović’s brand of body-as-site-of-trauma performance was turning the avant-garde on its head, attracting the attention of the public and institutions towards a previously reclusive and clandestine art mode. Like other zeitgeist-defining icons before her, it wasn’t just the strength of the work being created, but the magnetism of the artist herself which brought in the crowds. It’s why 561,471 visitors came to see The Artist is Present. It’s why HBO commissioned a documentary on her life and work, and it’s why, some seven years after we first spoke, Marina Abramović is still on my mind.

Marina & Dr Nonna Brenner in New York. © Marina Abramović Longevity Method

It’s wise then to remember that even personal heroes are fallible human beings. Following a not-quite-recent trend of turning performance into product, Abramović has collaborated with mentor and holistic medical therapist Dr Nonna Brenner on a wellness line that combines the aesthetics of Durex with the insidious menace of longevity influencers. It’s not too far removed from the rhetoric of billionaire-turned-immortality-vampire Bryan Johnson, who uses the language of health and wellness to advocate for a lifestyle catered towards achieving “biological youth” at any cost. “Reveal Your Natural Glow With Face Lotion” reads the text next to the £199 Abramović Institute moisturiser, with ingredients such as Vitamin C, White Bread and White Wine, listed in bold. Other products include the £99 Energy Drop which claims to help customers “unlock their natural energy” by taking 50-60 drops, twice a day between breakfast and dinner. This, Abramović confesses, is all part of a drive to alleviate society from the shackles of consumerism, writing that, “Our need for consumption allowed us to be consumed, and always keeps us hungry for new gadgets to buy. The result of all this is that we have lost our spiritual center.”

Marina Abramović Longevity Method collection (first edition) £459.00. © Marina Abramović Longevity Method

That Abramvoić claims these products possess the power to bypass the label of “new gadget to buy” and even the slippery clutches of capital is a performance art piece in and of itself.

But if Ambramovć is selling out, who is buying?

In recent weeks, the purchasing power of teenagers has caused a moral panic. Charm bracelets and handheld consoles have been swapped for retinol and niacinamide as tweens swarm the aisles of Boots and Sephora; ritual acts of dress-up evolving from awkwardly applied blue eyeshadow and a mother’s oversized heels, and into £40 vials of Vitamin A1. Skincare is a lucrative market, with an estimated GDP of £3.1 billion in the UK alone, but what do these consumption habits say about the life of a 12-year-old? That desire can be located in the pixelated graphic of a Glossier logo? That the fantasy of womanhood is encapsulated by a Drunk Elephant serum? As I look at my own skin, lightly lined by late nights and a lackadaisical approach to applying SPF, I wonder if they might be onto something. Perhaps if I had spent more time investing in alpha-hydroxy-acids, my face would look closer to the ultimate feminine ideal: wet dolphin. Maybe The Abramović Institute ‘Immune Drops’ will help.

Marina Abramović, Balkan Baroque, June 1997. Performance at XLVIII Venice Biennale; 4 days. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives. © Marina Abramović

The painful quest to achieve ideal forms of feminine beauty is easy fodder in the contemporary art world. In Orlan’s decade-spanning The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan, the French artist faced the lick of a surgeon’s knife in a series of operations that saw the artist undergo brow lifts, chin implants and eyelid modification to better resemble Botticelli’s Venus, Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Moreau’s Europa and Fontainbleu’s Diana. Image stills depict the artist bandaged and bruised, yellow fluids seeping through gauze as society’s annihilative idolisation of beauty is illuminated under the glare of a surgeon’s head torch. Similarly, in Juno Calypso’s A Dream in Green (2015), part of the Honeymoon Series, we see the photographer use the figure of ‘Joyce’ as an avatar through which to explore femininity. In the image, Joyce’s nude body, dipped in mint green, poses resplendently; an alien Aphrodite in a heart-shaped bath. Surrounded by mirrors, her self is reflected in panorama towards the viewer, her red hair cascading down her back in an uncanny-valley vision of Eve. At once moving and farcical, the work captures the familial relationship between beauty and the grotesque.

It’s tempting to place Abramović’s stunt in a canon of work that has long critiqued and questioned western ideals of beauty, yet the reality is much more disappointing. How does one reconcile the evolution of an artist that created the likes of Rhythm 0 (1974), Rhythm 5 (1974) and Balkan Baroque (2000), recently experienced at the artist’s major Royal Academy show, with a multi-millionaire business mogul that claims a luxury skincare line will help me “re-discover forgotten rituals and knowledge of the past.” The reality is, you can’t. Skincare will never really help me find my spiritual centre. Energy drops won’t put me on a path towards my truest, most enlightened self, and white wine belongs in my body, not on my face. The artist is present, but can she read the room?