Reginald Sylvester II is striving for pictorial heaven

16 min read

“I want to bring new sensibility, taste, and information to the culture and communities that I represent.”

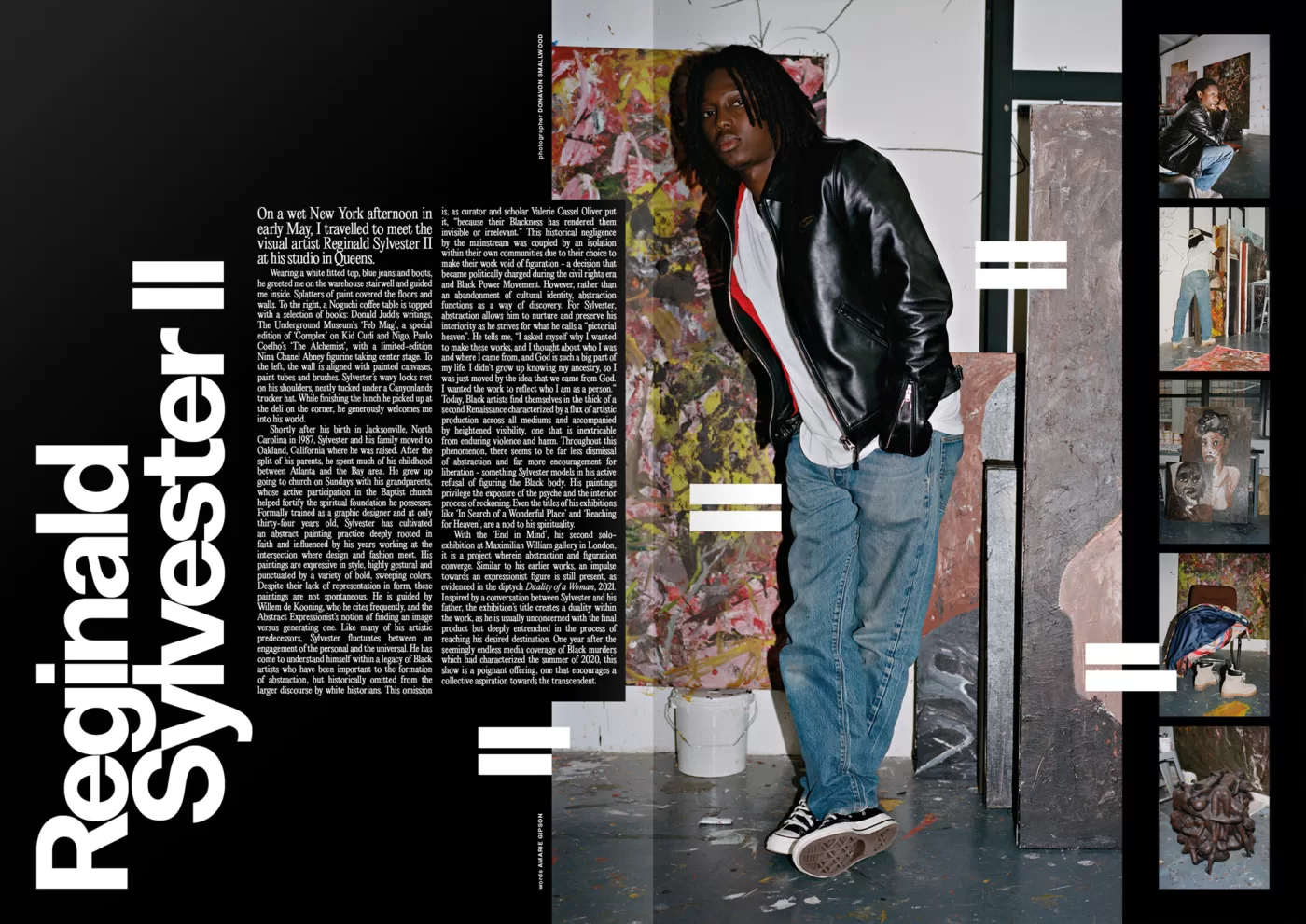

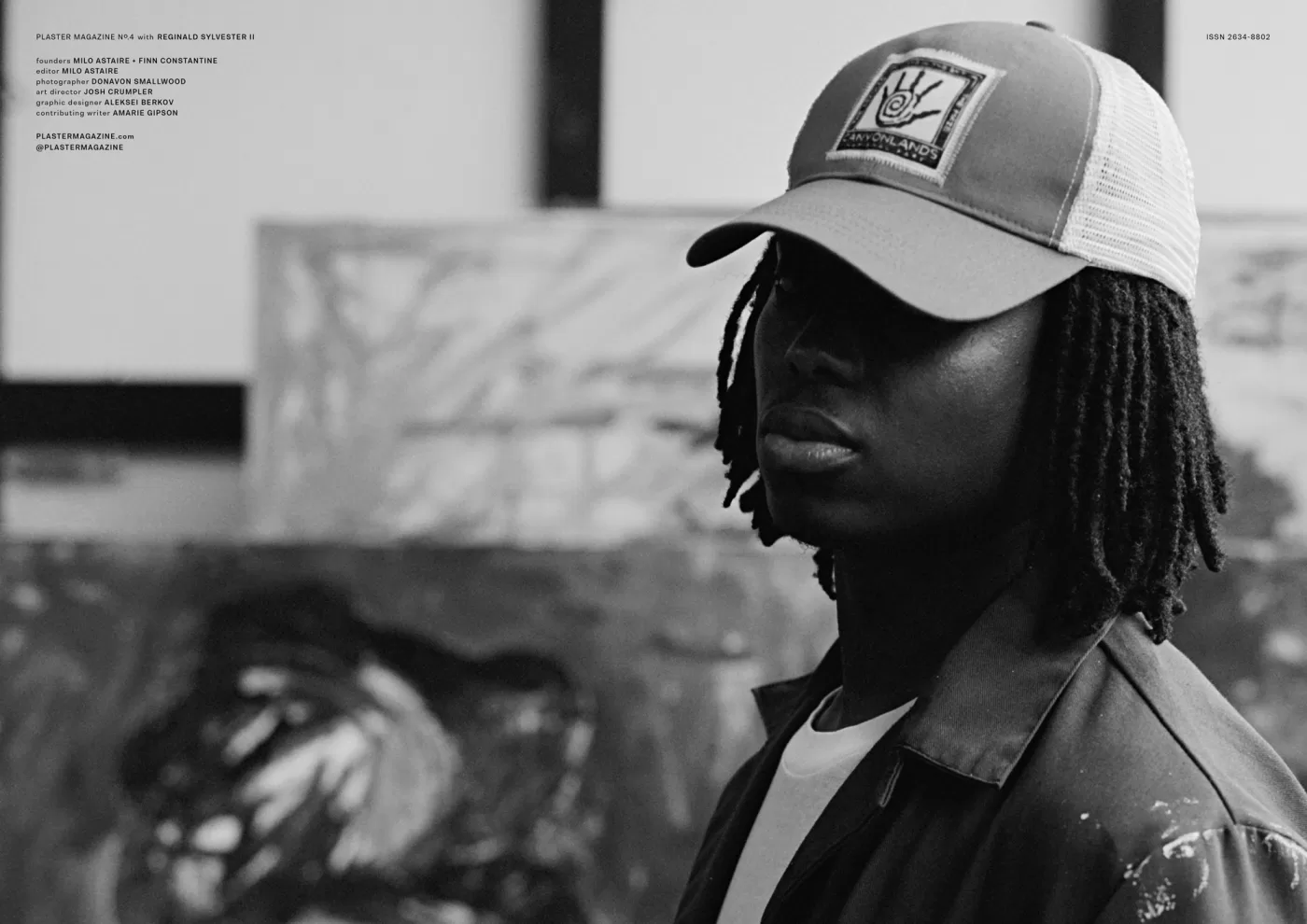

On a wet New York afternoon in early May, I travelled to meet the visual artist Reginald Sylvester II at his studio in Queens. Wearing a white fitted top, blue jeans and boots, he greeted me on the warehouse stairwell and guided me inside. Splatters of paint covered the floors and walls. To the right, a Noguchi coffee table is topped with a selection of books: Donald Judd’s writings, The Underground Museum’s Feb Mag, a special edition of Complex on Kid Cudi and Nigo, Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, with a limited edition Nina Chanel Abney figurine taking centre stage. To the left, the wall is aligned with painted canvases, paint tubes and brushes. Sylvester’s wavy locks rest on his shoulders, neatly tucked under a Canyonlands trucker hat. While finishing the lunch he picked up at the deli on the corner, he generously welcomes me into his world.

Shortly after his birth in Jacksonville, North Carolina in 1987, Sylvester and his family moved to Oakland, California where he was raised. After the split of his parents, he spent much of his childhood between Atlanta and the Bay area. He grew up going to church on Sundays with his grandparents, whose active participation in the Baptist church helped fortify the spiritual foundation he possesses. Formally trained as a graphic designer and at only thirty-four years old, Sylvester has cultivated an abstract painting practice deeply rooted in faith and influenced by his years working at the intersection where design and fashion meet. His paintings are expressive in style, highly gestural and punctuated by a variety of bold, sweeping colours. Despite their lack of representation in form, these paintings are not spontaneous. He is guided by Willem de Kooning, who he cites frequently, and the Abstract Expressionist’s notion of finding an image versus generating one. Like many of his artistic predecessors, Sylvester fluctuates between an engagement of the personal and the universal. He has come to understand himself within a legacy of Black artists who have been important to the formation of abstraction but historically omitted from the larger discourse by white historians. This omission is, as curator and scholar Valerie Cassel Oliver put it, “because their Blackness has rendered them invisible or irrelevant.” This historical negligence by the mainstream was coupled with isolation within their own communities due to their choice to make their work void of figuration – a decision that became politically charged during the civil rights era and Black Power Movement. However, rather than an abandonment of cultural identity, abstraction functions as a way of discovery. For Sylvester, abstraction allows him to nurture and preserve his interiority as he strives for what he calls a “pictorial heaven”. He tells me, “I asked myself why I wanted to make these works, and I thought about who I was and where I came from, and God is such a big part of my life. I didn’t grow up knowing my ancestry, so I was just moved by the idea that we came from God. I wanted the work to reflect who I am as a person.” Today, Black artists find themselves in the thick of a second Renaissance characterised by a flux of artistic production across all mediums and accompanied by heightened visibility, one that is inextricable from enduring violence and harm. Throughout this phenomenon, there seems to be far less dismissal of abstraction and far more encouragement for liberation – something Sylvester models in his active refusal of figuring the Black body. His paintings privilege the exposure of the psyche and the interior process of reckoning. Even the titles of his exhibitions like ‘In Search of a Wonderful Place’ and ‘Reaching for Heaven’, are a nod to his spirituality.

With the ‘End in Mind’, his second solo exhibition at Maximilian William Gallery in London, it is a project wherein abstraction and figuration converge. Similar to his earlier works, an impulse towards an expressionist figure is still present, as evidenced in the diptych Duality of a Woman, 2021. Inspired by a conversation between Sylvester and his father, the exhibition’s title creates a duality within the work, as he is usually unconcerned with the final product but deeply entrenched in the process of reaching his desired destination. One year after the seemingly endless media coverage of Black murder(s) / the murder of a Black man (which had characterized the summer of 2020), this show is a poignant offering, one that encourages a collective aspiration towards the transcendent.

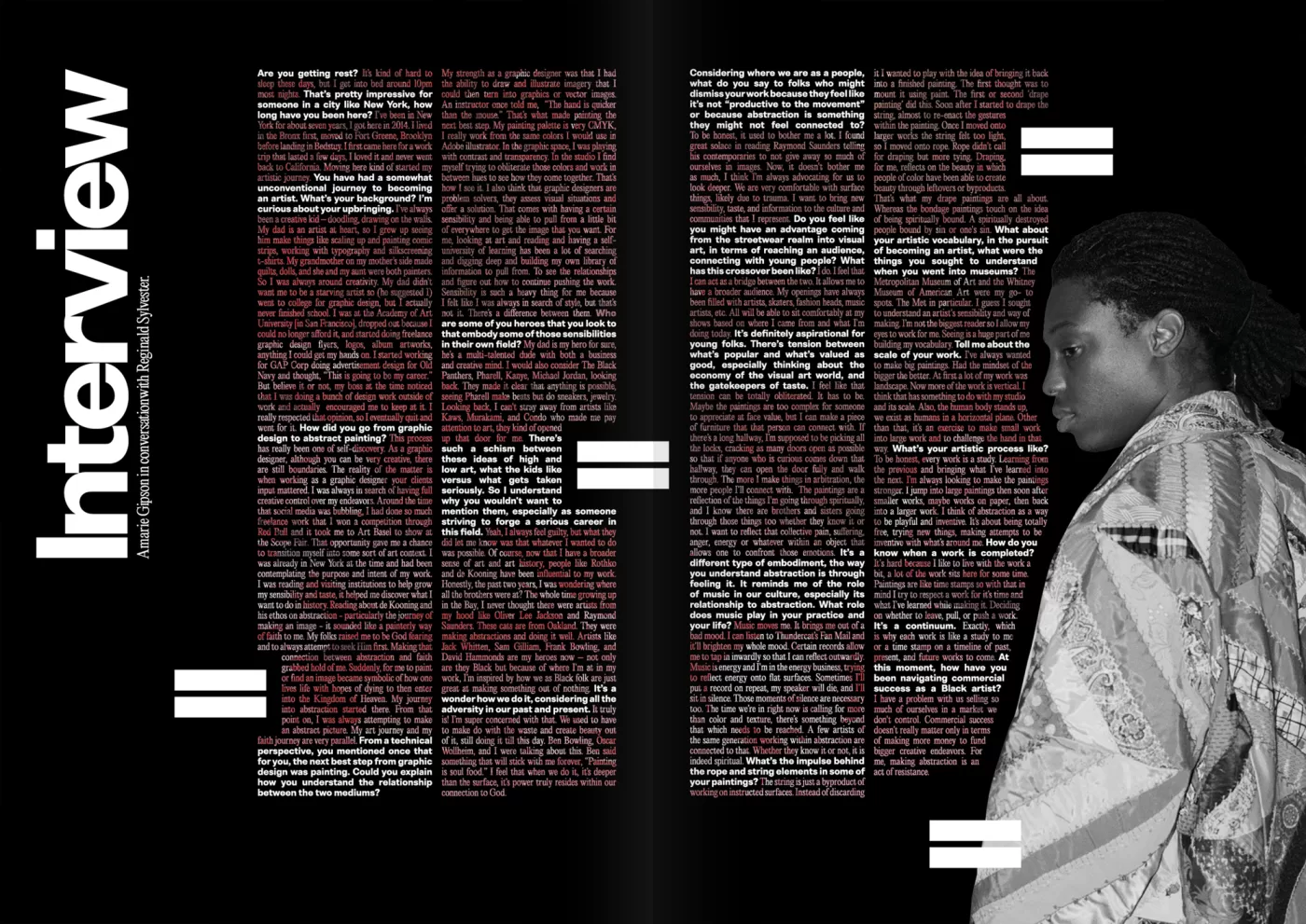

Are you getting rest?

It’s kind of hard to sleep these days, but I get into bed around 10pm most nights.

That’s pretty impressive for someone in a city like New York, how long have you been here?

I’ve been in New York for about seven years, I got here in 2014. I lived in the Bronx first, moved to Fort Greene, Brooklyn before landing in Bedstuy. I first came here for a work trip that lasted a few days, I loved it and never went back to California. Moving here kind of started my artistic journey.

You have had a somewhat unconventional journey to becoming an artist. What’s your background? I’m curious about your upbringing.

I’ve always been a creative kid – doodling, drawing on the walls. My dad is an artist at heart, so I grew up seeing him make things like scaling up and painting comic strips, working with typography and silkscreening t-shirts. My grandmother on my mother’s side made quilts, dolls, and she and my aunt were both painters. So I was always around creativity. My dad didn’t want me to be a starving artist so he suggested I went to college for graphic design, but I actually never finished school. I was at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, dropped out because I could no longer afford it, and started doing freelance graphic design flyers, logos, album artworks, anything I could get my hands on. I started working for GAP Corp. doing advertisement design for Old Navy and thought, “This is going to be my career.” But believe it or not, my boss at the time noticed that I was doing a bunch of design work outside of work and actually encouraged me to keep at. I really respected that opinion, so I eventually quit and went for it.

How did you go from graphic design to abstract painting?

This process has really been one of self-discovery. As a graphic designer, although you can be very creative, there are still boundaries. The reality of the matter is when working as a graphic designer your clients input mattered. I was always in search of having full creative control over my endeavors. Around the time that social media was bubbling, I had done so much freelance work that I won a competition through Red Bull and it took me to Art Basel to show at the Scope Fair. That opportunity gave me a chance to transition myself into some sort of art context. I was already in New York at the time and had been contemplating the purpose and intent of my work. I was reading and visiting institutions to help grow my sensibility and taste, it helped me discover what I want to do in history. Reading about de Kooning and his ethos on abstraction – particularly the journey of making/finding an image – it sounded like a painterly way of faith to me. My folks raised me to be God fearing and to always attempt to seek Him first. Making that connection between abstraction and faith grabbed hold of me. Suddenly, for me to paint or find an image became symbolic of how one lives life with hopes of dying to then enter into the Kingdom of Heaven. My journey into abstraction started there. From that point on, I was always attempting to make an abstract picture. My art journey and my faith journey are very parallel.

From a technical perspective, you mentioned once that for you, the next best step from graphic design was painting. Could you explain how you understand the relationship between the two mediums?

My strength as a graphic designer was that I had the ability to draw and illustrate imagery that I could then turn into graphics or vector images. An instructor once told me, “The hand is quicker than the mouse.” That’s what made painting the next best step. My painting palette is very CMYK, I really work from the same colors I would use in Adobe illustrator. In the graphic space, I was playing with contrast and transparency. In the studio I find myself trying to obliterate those colors and work in between hues to see how they come together. That’s how I see it.

I also think that graphic designers are problem solvers, they assess visual situations and offer a solution. That comes with having a certain sensibility and being able to pull from a little bit of everywhere to get the image that you want. For me, looking at art and reading and having a self-university of learning has been a lot of searching and digging deep and building my own library of information to pull from. To see the relationships and figure out how to continue pushing the work. Sensibility is such a heavy thing for me because I felt like I was always in search of style, but that’s not it. There’s a difference between them.

Who are some of you heroes that you look to that embody some of those sensibilities in their own field?

My dad is my hero for sure, he’s a multi-talented dude with both a business and creative mind. I would also consider The Black Panthers, Pharell, Kanye, Michael Jordan, looking back. They made it clear that anything is possible, seeing Pharell make beats but do sneakers, jewelry. Looking back, I can’t stray away from artists like Kaws, Murakami, and Condo who made me pay attention to art, they kind of opened up that door for me.

There’s such a schism between these ideas of high and low art, what the kids like versus what gets taken seriously. So I understand why you wouldn’t want to mention them, especially as someone striving to forge a serious career in this field.

Yeah, I always feel guilty, but what they did let me know was that whatever I wanted to do was possible. Of course, now that I have a broader sense of art and art history, people like Rothko and de Kooning have been influential to my work. Honestly, the past two years, I was wondering where all the brothers were at? The whole time growing up in the Bay, I never thought there were artists from my hood like Oliver Lee Jackson and Raymond Saunders. These cats are from Oakland. They were making abstractions and doing it well. Artists like Jack Whitten, Sam Gilliam, Frank Bowling and David Hammonds are my heroes now – not only are they Black but because of where I’m at in my work, I’m inspired by how we as Black folk are just great at making something out of nothing.

It’s a wonder how we do it, considering all the adversity in our past and present.

It truly is! I’m super concerned with that. We used to have to make do with the waste and create beauty out of it, still doing it till this day. Ben Bowling, Oscar Wollheim, and I were talking about this. Ben said something that will stick with me forever, “Painting is soul food.” I feel that when we do it, it’s deeper than the surface, its power truly resides within our connection to God.

Considering where we are as a people, what do you say to folks who might dismiss your work because they feel like it’s not “productive to the movement” or because abstraction is something they might not feel connected to?

To be honest, it used to bother me a lot. I found great solace in reading Raymond Saunders telling his contemporaries to not give away so much of ourselves in images. Now, it doesn’t bother me as much, I think I’m always advocating for us to look deeper. We are very comfortable with surface things, likely due to trauma. I want to bring new sensibility, taste, and information to the culture and communities that I represent.

Do you feel like you might have an advantage coming from the streetwear realm into visual art, in terms of reaching an audience, connecting with young people? What has this crossover been like?

I do. I feel that I can act as a bridge between the two. It allows me to have a broader audience. My openings have always been filled with artists, skaters, fashion heads, music artists, etc. All will be able to sit comfortably at my shows based on where I came from and what I’m doing today.

It’s definitely aspirational for young folks. There’s definitely tension between what’s popular and what’s valued as good, especially thinking about the economy of the visual art world, and the gatekeepers of taste.

I feel like…that tension can be totally obliterated. It has to be. Maybe the paintings are too complex for someone to appreciate at face value, but I can make a piece of furniture that that person can connect with. If there’s a long hallway, I’m supposed to be picking all the locks, cracking as many doors open as possible so that if anyone who is curious comes down that hallway, they can open the door fully and walk through. The more I make things in arbitration, the more people I’ll connect with. The paintings are a reflection of the things I’m going through spiritually, and I know there are brothers and sisters going through those things too whether they know it or not. I want to reflect that collective pain, suffering, anger, energy or whatever within an object that allows one to confront those emotions.

It’s a different type of embodiment, the way you understand abstraction is through feeling it. It reminds me of the role of music in our culture, especially its relationship to abstraction. What role does music play in your practice and your life?

Music moves me. It brings me out of a bad mood. I can listen to Thundercat’s Fan Mail and it’ll brighten my whole mood. Certain records allow me to tap in inwardly so that I can reflect outwardly. Music is energy and I’m in the energy business, trying to reflect energy onto flat surfaces. Sometimes I’ll put a record on repeat, my speaker will die and I’ll sit in silence. Those moments of silence are necessary too. The time we’re in right now is calling for more than color and texture, there’s something beyond that which needs to be reached. A few artists of the same generation working within abstraction are connected to that. Whether they know it or not, it is indeed spiritual.

What’s the impulse behind the rope and string elements in some of your paintings?

The string is just a byproduct of working on instructed surfaces. Instead of discarding it I wanted to play with the idea of bringing it back into a finished painting. The first thought was to mount it using paint. The first or second ‘drape painting’ did this. Soon after I started to actually drape the string, almost to reenact the gestures within the painting. Once I moved onto larger works the string felt too light, so I moved onto rope. Rope didn’t call for draping but more so tying and ponding. Draping, for me, reflects on the beauty in which people of color have been able to create beauty through leftovers or byproducts. That’s what my drape paintings are all about. Whereas the bondage paintings touch on the idea of being spiritually bound. A spiritually destroyed people bound by sin or one’s sin.

What about your artistic vocabulary, in the pursuit of becoming an artist, what were the things you sought to understand when you went into museums?

The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art were my go-to spots. The Met in particular. I guess I sought to understand an artist’s sensibility and way of making. I’m not the biggest reader so I allow my eyes to work for me. Seeing is a huge part of me building my vocabulary.

Tell me about the scale of your work.

I’ve always wanted to make big paintings. Had the mindset of bigger then better. At first a lot of my work was landscape. Now more of the work is horizontal. I think that has something to do with my studio and its scale. Also, the human body stands up, we exist as humans in a horizontal plane. Other than that, it’s an exercise to make small work into large work and to challenge the hand in that way.

What’s your artistic process like?

To be honest, every work is a study. Learning from the previous and bringing what I’ve learned into the next. I’m always looking to make the paintings stronger. I jump into large paintings then soon after smaller works, maybe works on paper, then back into a larger work. I think of abstraction as a way to be playful and inventive. It’s about being totally free, trying new things, making attempts to be inventive with what’s around me.

How do you know when a work is completed?

It’s hard because I like to live with the work a bit, a lot of the work sits here for some time. Paintings are like time stamps so with that in mind I try to respect a work for its time and what I’ve learned while making it. Deciding on whether to leave, pull, or push a work.

It’s a continuum.

Exactly, which is why each work is like a study to me or a time stamp on a timeline of past, present, and future works to come.

At this moment, how have you been navigating commercial success as a Black artist?

I have a problem with us selling so much of ourselves in a market we don’t control. Commercial success doesn’t really matter only in terms of making more money to fund bigger creative endeavors. For me, making abstraction is an act of resistance.