Are “frenzied women” born or made? Eloise Hendy on Nan Goldin

9 min read

When it was first shown, 75 people fainted. Now Nan Goldin’s guttural ode to rebellious girls and chosen family arrives in London

Nan Goldin, My mother pregnant © Nan Goldin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

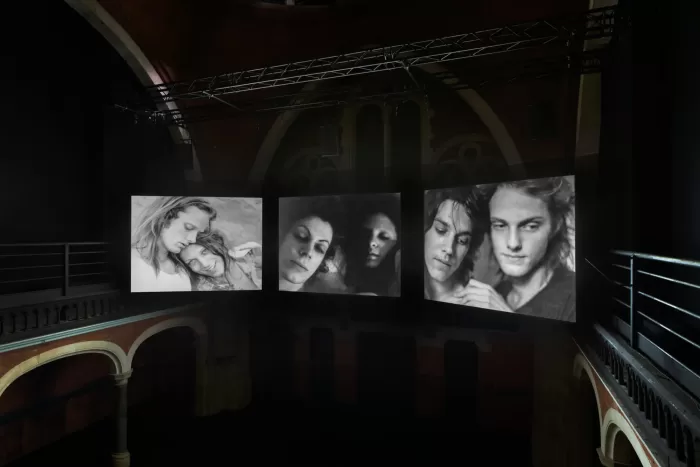

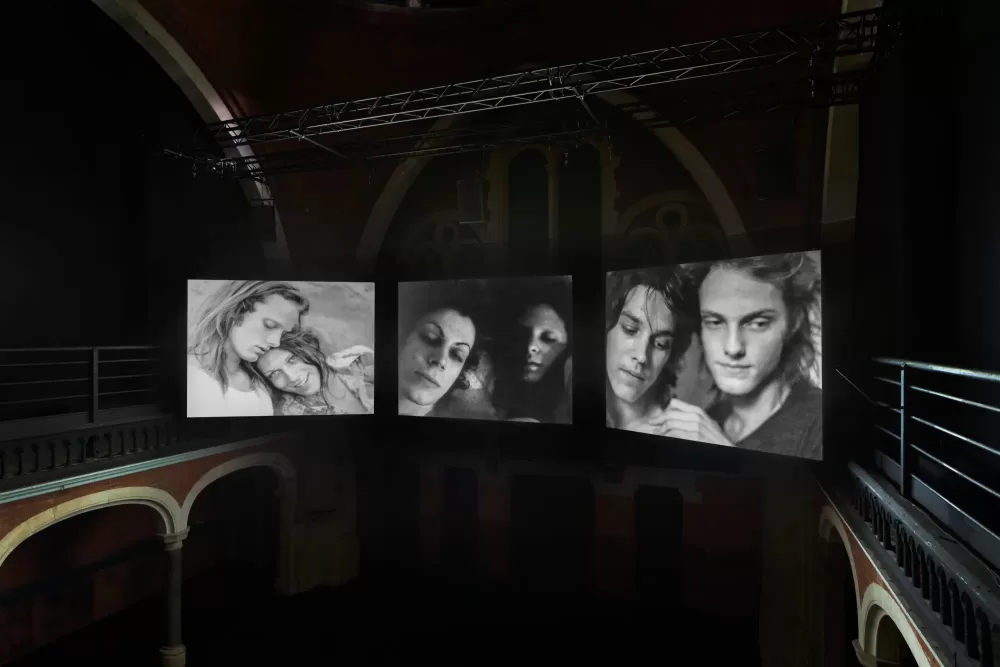

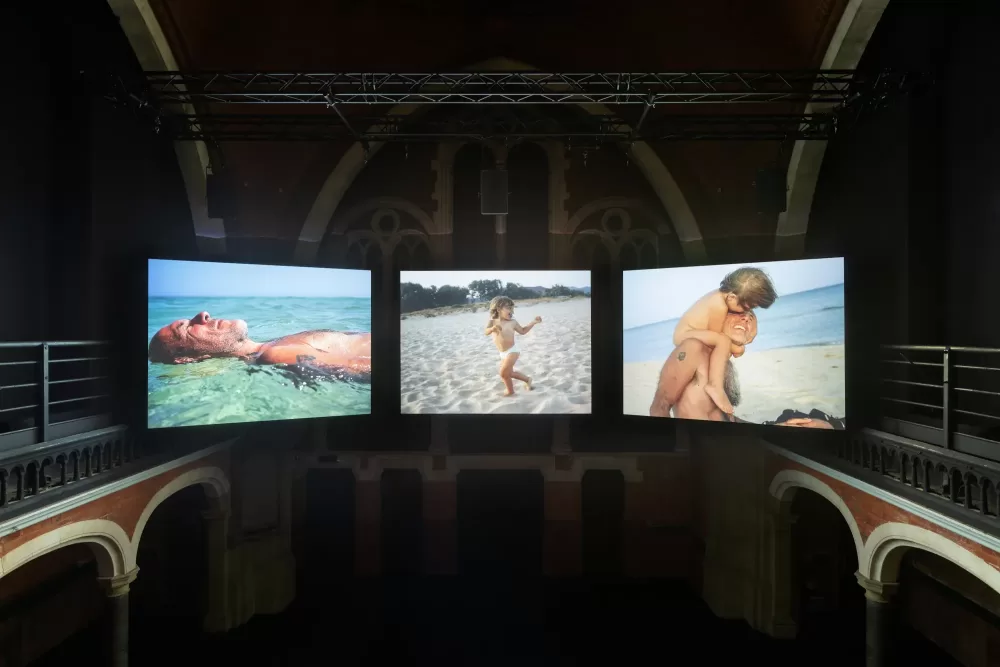

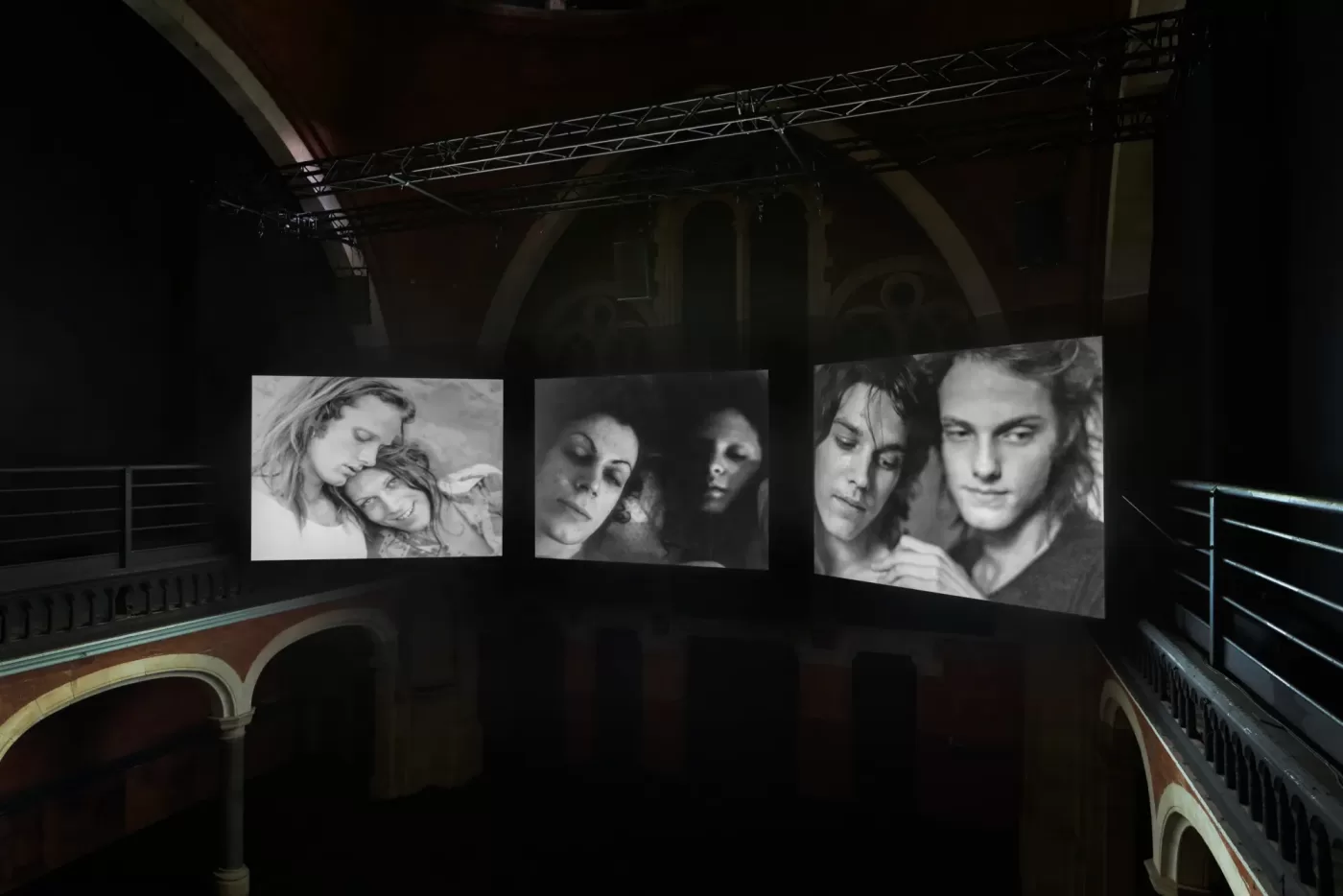

When Nan Goldin’s film Sisters, Saints, Sibyls was first shown in Paris, 75 people fainted. One sequence of images, in particular, prompted the audience’s distress: a series of stills of Goldin burning her forearm with a lit cigarette. Other wounds run up her arm from earlier episodes of self-harming. They are deep and weeping, with blackened edges, as if her flesh is being eaten away from the inside out – as if, rather than burning herself, she is being devoured.

These distressing scenes were captured while Goldin was undergoing addiction treatment at The Priory – the infamous private mental health hospital that resembles a “white Gothic mansion” and whose name carries the whiff of religious seclusion. It is a darkly fitting setting, for Sisters, Saints, Sibyls is a religious Gothic of sorts; a modern myth about seclusion and incarceration; teenage rebellion and generational trauma; suicide and suburbia.

Still from Nan Goldin, Sisters, Saints, Sibyls, 2004–22. © Nan Goldin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

The saint’s story comes first. “Barbara, who has reached the age of puberty, lives with her father,” a voice-over narrates as Mediaeval paintings appear over the film’s three screens. “She grows to be a very beautiful girl and is courted far and wide. Her father is obsessed and decides to build a tower with two windows to lock her in until she is married”. While confined, Barbara converts to Christianity and is eventually sentenced to death for it. “Though tortured, humiliated, flogged and mutilated, Barbara refuses to betray her faith,” the narration reads over images of Barbara being bound and stabbed. Barbara’s father voluntarily beheads her, and is instantly struck by lightning.

This mythological narrative of entrapment, torment and rebellion bears an uncanny closeness to that of Goldin’s older sister, Barbara Holly Goldin, whose story comes next. “My sister taught me to hate suburbia from a very young age,” Goldin once said: “the suffocation, the double standards. ‘Don’t let the neighbours know’, was the gospel. Well, the neighbours certainly knew what was going on in our house, because they heard it.” Here, photos of the Goldin family home are punctured by screams of Slut! and Whore!, as if emotional violence is still haunting the bricks. Goldin also includes a choice line from one of her sister’s psychiatric records suggesting it was Mrs Goldin who should have been in the hospital, not Miss Goldin. But, instead, Barbara was moved from institution to institution: orphanage, hospital, psychiatric detention centre. In 1965, just a few weeks before Barbara turned 19, she lay down on a railway track as a train approached. “Tell the children it was an accident,” Mrs Goldin told the police. In a text accompanying a 2009 screening of the film, Nan Goldin described this as the “moment of clarity that defined [her] life”. As the film footage tracks Goldin returning to the spot where Barbara died, it is clear that it is not just the trauma of her sister’s suicide, but also the suburban culture of secrecy and suppression that gets under Nan Goldin’s skin. It is her mother’s “tyranny of revisionism” that devours her.

Still from Nan Goldin, Sisters, Saints, Sibyls, 2004–22. © Nan Goldin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Still from Nan Goldin, Sisters, Saints, Sibyls, 2004–22. © Nan Goldin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

And the sibyls? They were Ancient Greek prophetesses, described by Greek mythology scholar Walter Burkert as “frenzied women from whose lips the god speaks”. Here, one line conjures another twisted narrative of confinement and escape: Goldin reveals that Barbara told Nan her doctors said she would end up like her sister. “I thought I had to die at 18,” Goldin confesses. It was this fear of the fatalistic effect of her upbringing that led Goldin to leave home at 14.

Yet, the allusion to sibyls hints at a broader point about “madness” and “sickness”. For are “frenzied women” born, or made? “The only reaction against an unbearable society is equally unbearable nonsense,” Kathy Acker wrote; Goldin’s Instagram bio currently reads “Much Madness is divinest Sense”. Across the three screens women split and double: Mrs Goldin and the two Miss Goldins; the two tormented and resolute Barbaras; Nancy Goldin the woman and ‘Nan’ the artist; saints, sisters and “frenzied women” speaking “divinest sense” all knotted together in a triptych. By the time Goldin displays her charred flesh in the clinic, the knot has been pulled tight. Each of her self-inflicted cigarette wounds seems to gesture outwards to the burning of female martyrs, sacred stigmata, and the horribly mundane self-scarring of clinically depressed girls. Is it any wonder that 75 witnesses lost consciousness, as if by setting fire to herself Goldin had also struck them with lightning through the screen?

Nan Goldin, My bedroom at The Lodge, Belmont, MA, 1988. © Nan Goldin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

“If you can make somebody faint from your work, it doesn’t get better, right?” Goldin told The Guardian in a recent interview. Certainly, collective fainting seems like the most apt reaction to this work specifically. That incident occurred in 2004, while the three-channel video was being presented in the chapel of Paris’ Hopital de la Salpetriere, which was founded in the 17th century as an asylum for women suffering from mental illness. Occurring in this space, the mass fainting event is given an added frisson – appearing not only as a spontaneous, embodied response to witnessing Goldin’s self-mutilation, but weighted with the entire, loaded history of psychogenic illness, hysteria and social contagion. At the same time, Goldin’s fainting audience has another metaphorical power. Losing consciousness at the moment of witnessing Goldin’s slow, deliberate self-mutilation, the 75 fainters also speak to society’s desire to look away, block out, and suppress knowledge of self-abuse and mental distress; to keep it at a remove. This, after all, is one of the essential principles of asylums like Salpetriere and institutions like The Priory. Care relies on incarceration. Treatment resembles punishment. As Goldin’s audience passes out, they also become actors in the artist’s knotted narrative – representing both the “hysterics” locked in the asylum and the society looking away. Who is really mad here?

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

Now, two decades on, Sisters, Saints, Sibyls is being shown in London, in a deconsecrated Welsh Chapel on Charing Cross Road. Yet, this time, Goldin cut the self-harm scene down. “There were two more minutes of me burning myself, but I edited it out,” Goldin told The Gentlewoman last year. “It became relentless.” Gazing upon Goldin’s wounds as music soars up to the chapel’s domed roof, some of the “discipline and punish” atmosphere of Salpetriere (Foucault died there aged 57) seems to lift.

There is, of course, a long history of artists being read as visionaries. “Woman artists” making work out of the stuff of themselves are especially caught in a split between “mystic” and “monster”, but the entire “tortured artist” cliche relies on an idealisation of isolation, seclusion, and inner torment. By presenting a dark, mythic genealogy of female pain and punishment, Sisters, Saints, Sibyls threatens to endorse this vision. Yet, ultimately, the film is about escaping legacies of harm. It is a work about unbelief, and rewriting the future instead of the past. If Goldin finds transcendence, it is in her chosen family. The film’s closing sections are a paean to community, connection and love; a secular salvation. Without applying any of the gloss of romanticisation, Goldin offers hope.

Nan Goldin’s Sisters, Saints, Sibyls is on view at Gagosian Open until 23rd June 2024. gagosian.com