The hauntings of Pablo Picasso

8 min read

From Hannah Gadsby’s exorcism at the Brooklyn Museum to a narcissistic show at the Lugwig, this year has been all about the ceaseless haunting of Picasso, 50 years after his death. Sam Moore asks: why are we all still so obsessed?

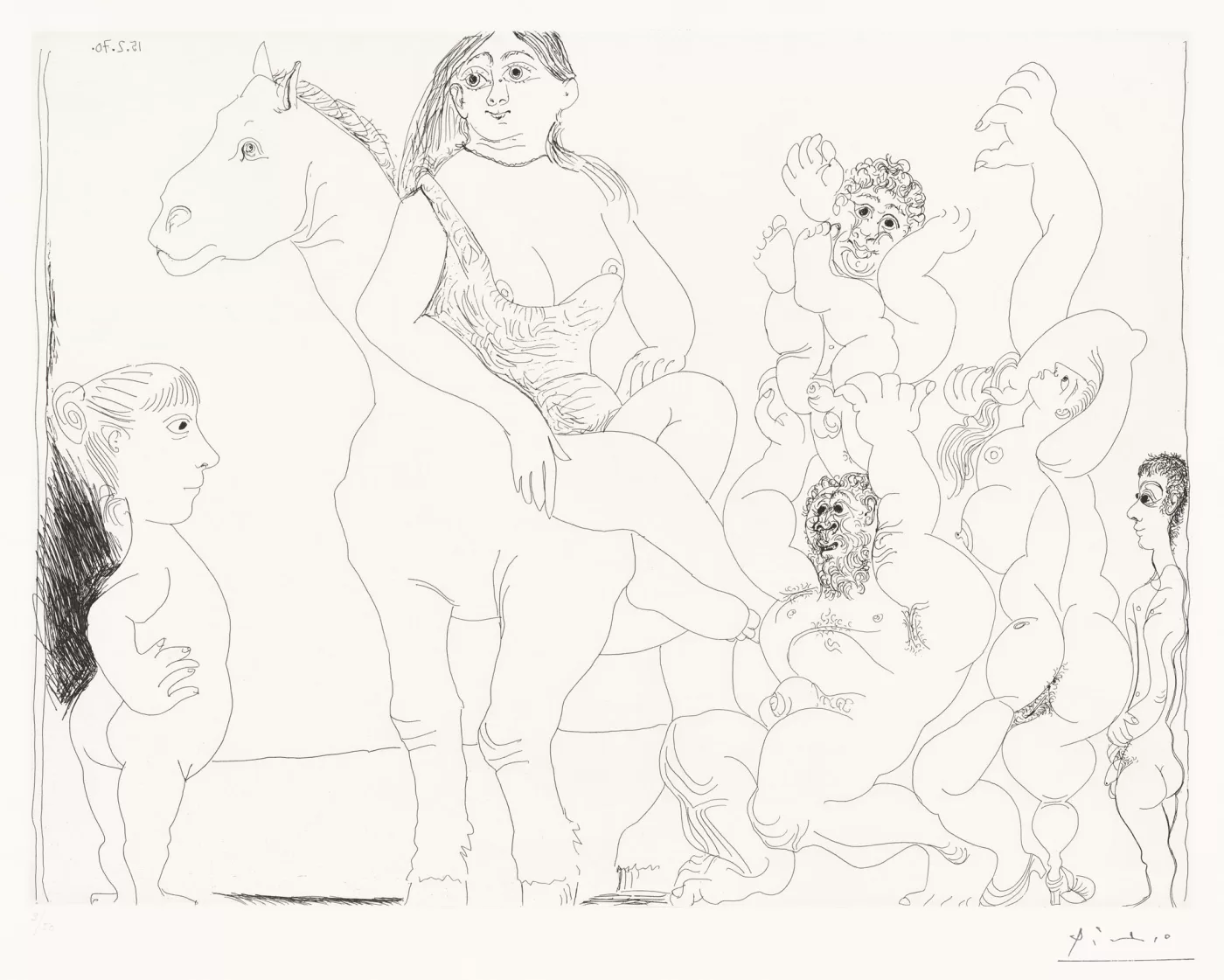

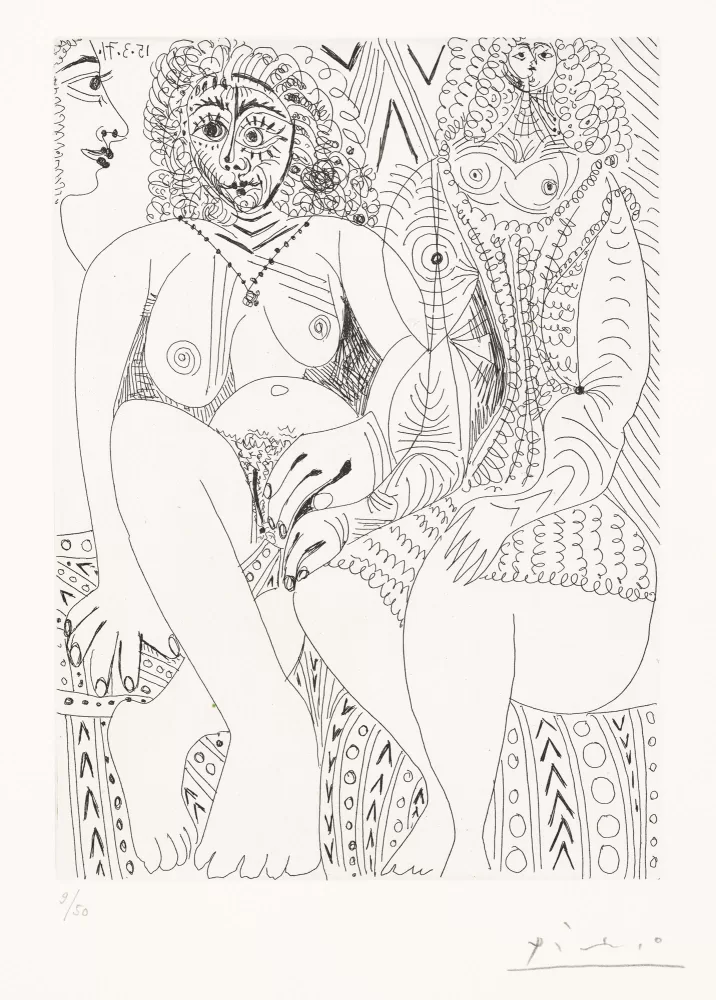

Pablo Picasso, Suite 156 (sheet 21), Museum Ludwig, Cologne © Succession Picasso/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023 Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

A spectre is haunting art history – the spectre of Pablo Picasso. The artist has been gone for five decades now, a milestone being marked by exhibitions grappling with his legacy all over the world. And yet curators, museums, comedians and more, still aren’t exactly sure if The Culture writ large needs or wants a man like Picasso anymore.

Hannah Gadsby ends up agreeing with the cubist – in spite of their clear disdain for both the man and his work – when, near tears at the end of their stand-up special Nanette (2018), they say that “we could paint a better world if we could see it from all perspectives.” They say this in spite of finding actual perspective(s) in Picasso’s art to be deeply limiting – bemoaning, for example, that none of those perspectives are a woman’s – and describe him as someone who “put a kaleidoscope filter on [his] cock.” And to paraphrase Gadsby themselves, you don’t hear too much stand-up comedy about art history, so, you’re welcome.

'It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According To Hannah Gadsby' at the Brooklyn Museum, 2023. Photo: Danny Perez

'It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According To Hannah Gadsby' at the Brooklyn Museum, 2023. Photo: Danny Perez

Gadsby’s combative relationship with the divisive cubist matters because they were asked to co-curate an exhibition on Picasso’s legacy for The Brooklyn Museum earlier this year: ‘It’s Pablo-Matic’, with the sub-head, Picasso according to Hannah Gadsby. There’s not too much to say about ‘Pablo-Matic’ that hasn’t already been said, but – whatever its merits might be, and no matter how frustrating some of the surface-level gestures towards satire and criticism seem to be – the show remains interesting as a way of grappling with that spectre of Picasso, with Gadsby and their collaborators seemingly trying to exorcise him from the soul of art history, to make space for other artists where Picasso allowed none (which raises more curatorial questions). ‘Pablo-Matic’ shows Picasso as a figure who’s haunting history, but what it doesn’t do is grapple with the idea that Picasso himself is haunted, and that’s why his perspective(s) could never be universal, and could never truly account for everyone – because Picasso was always trying to exorcise some of his own artistic ghosts and demons.

'It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According To Hannah Gadsby' at the Brooklyn Museum, 2023. Photo: Danny Perez

'It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According To Hannah Gadsby' at the Brooklyn Museum, 2023. Photo: Danny Perez

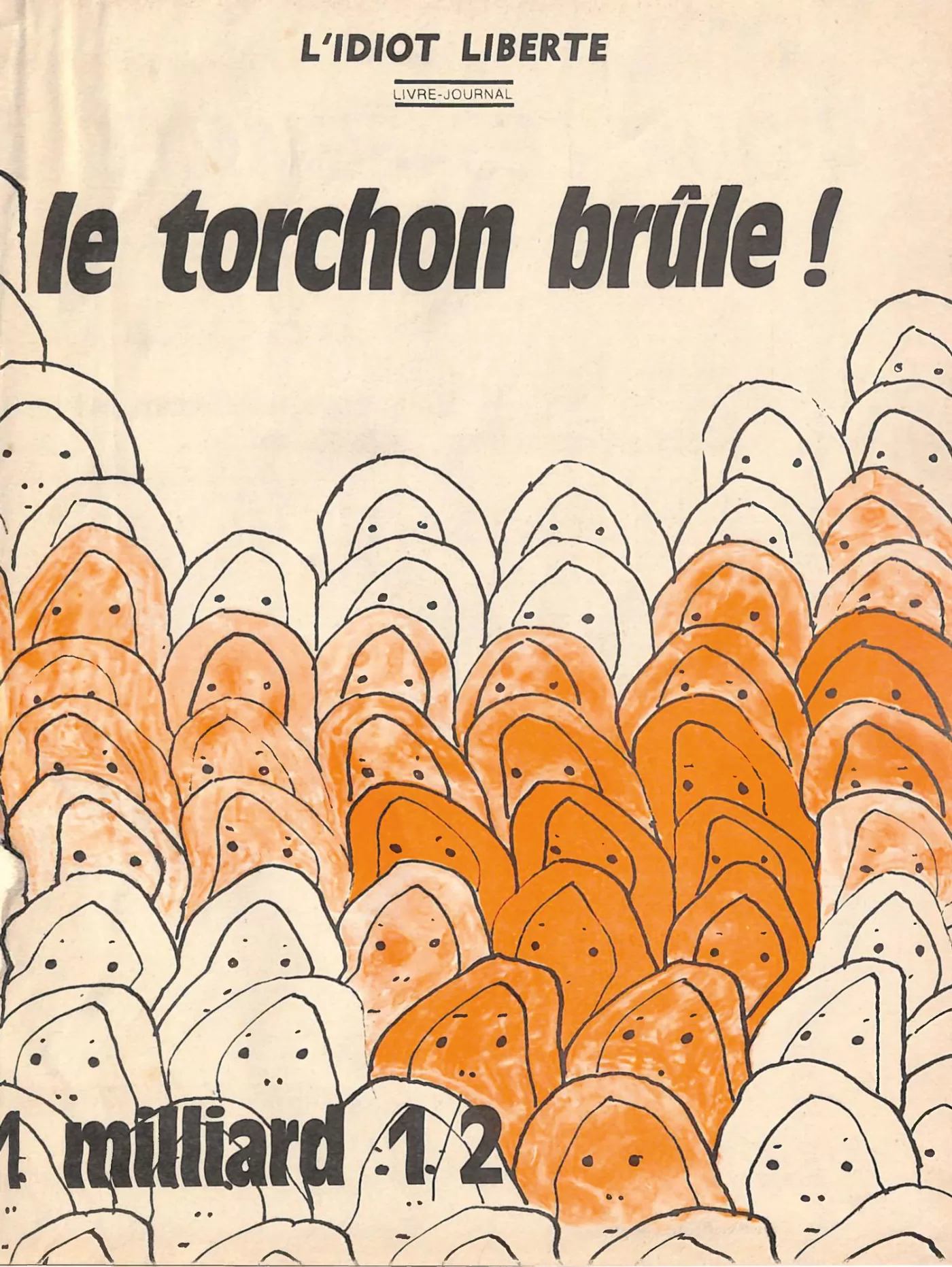

As part of the global celebration/reckoning that’s come with the 50th year of Picasso’s passing, the Ludwig Museum is showing ‘Suite 156’ from its permanent collection; a series of late works by the artist: etchings full of desire, violence and ghosts. This is placed in contrast with the feminist work that was being made during the same period as the etchings – 1968-72 – showcasing the kind of work that now, decades later, offers a contemporary counterpoint to Picasso’s in the form of the magazine Le Torchon Brûle, founded by MLF, a feminist liberation group of artists and activists. The bodies in Picasso’s work are placed into a combative conversation with the work of female artists.

But the thing that struck me most when walking through the quiet, dimly-lit rooms of the Ludwig Museum wasn’t necessarily the psychosexual contortions female bodies are subjected to under Picasso’s gaze. Instead, there’s a certain, named figure that lingers in the background of the etchings – someone far more defined than the archetypal images of model, debaucher and prostitute that recur throughout. Picasso places, voyeuristically, the image of Degas looking on at Picasso’s work.

Le Torchon Brûle Cover of the first issue, December 1970. Illustration: Gille Wittig © Marie Dedieu

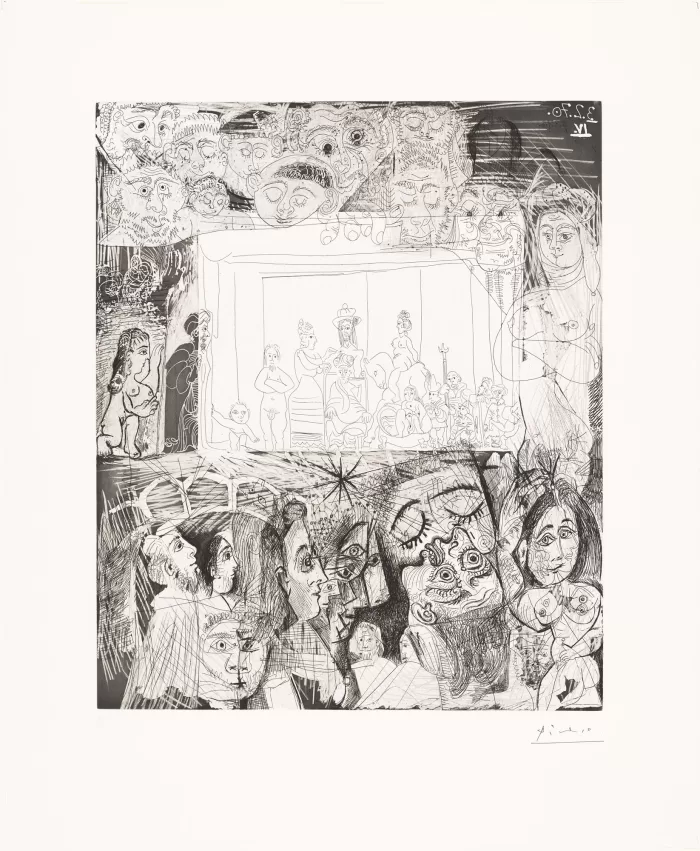

Throughout ‘Suite 156’, Picasso turns old masters into onlookers and responds in his own idiosyncratic way to their work. One of the etchings is Picasso’s response to the Rembrandt print Christ Presented to the People (1655). Picasso’s Variation on Rembrandt’s Ecce Homo (1970) makes the figures of Pilate and Christ much less distinct. At first glance, this doesn’t feel like a Passion piece at all; instead, it’s Picasso’s manipulation of the chorus of onlookers that becomes the focal point. Where the presentation of Christ to the people is a series of almost dashed-off line drawings, the people are a fascinating, almost monstrous amalgamation. Faces fuse, eyes smash together; some weep and some smile. It’s as if Picasso himself, in saying behold the man, is talking about himself, trying to make peace with the demons of art history in a way that makes room for himself, just like, decades later, institutions are trying to exorcise the lingering spirit of Picasso himself.

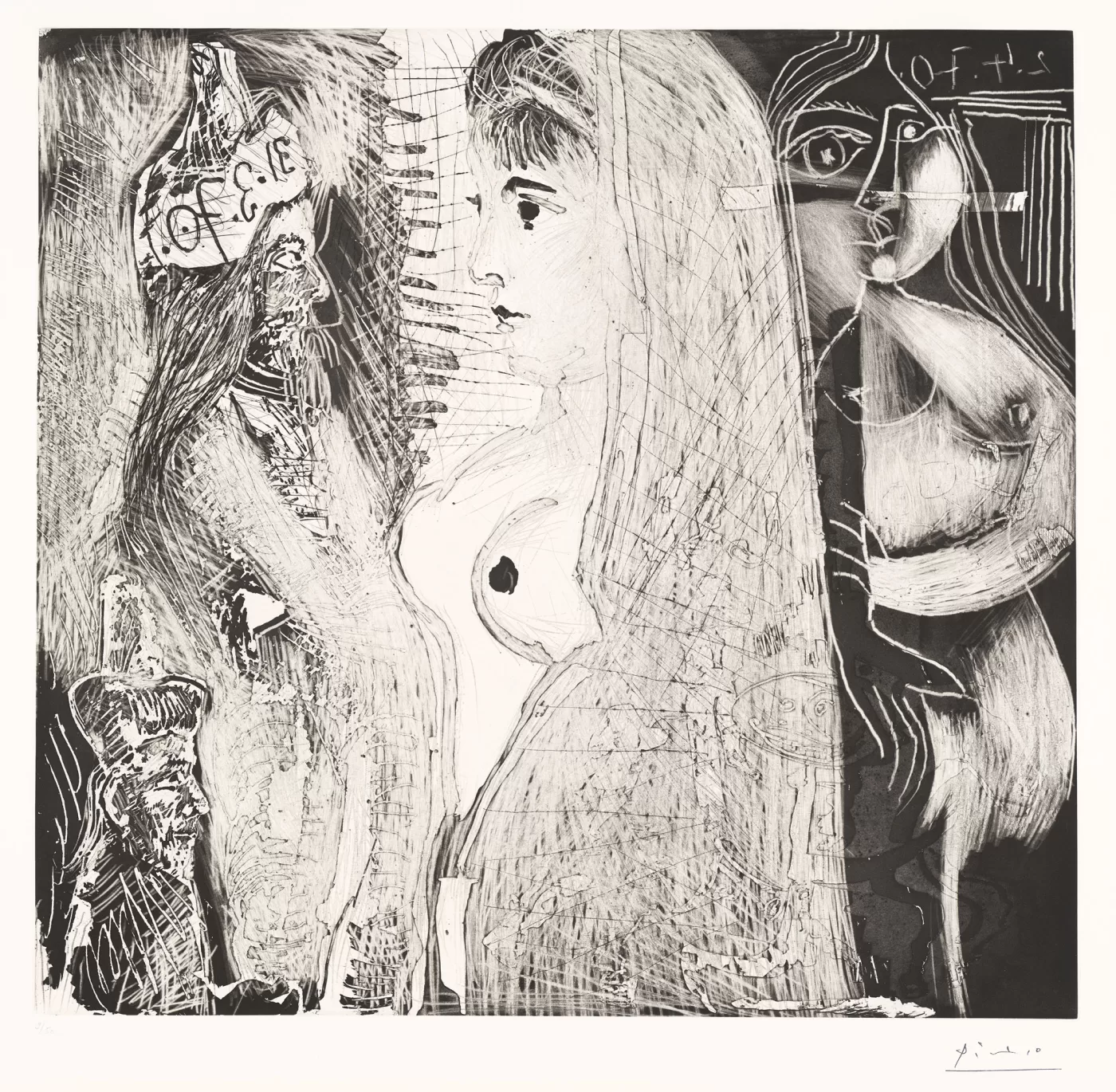

Pablo Picasso, Variation on Rembrandt’s Ecce Homo, 1970, Museum Ludwig, Cologne © Succession Picasso/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023 Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

Pablo Picasso, Suite 156 (sheet 83), Museum Ludwig, Cologne © Succession Picasso/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023 Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

When I think about the act of haunting, the idea of ghosts, I think most often about repetition; the idea that these are figures who are doomed to repeat the same actions and gestures over and over again until the end of the time. And, just as Picasso grappled with the ghosts of Degas and Rembrandt, we see curators like Gadsby grappling with the ghost of Picasso. The more things change, the more they stay the same. It leaves me wondering if, 50 years from now, as museums and curators and writers grapple with Picasso’s centenary, we’ll continue to be haunted, continue to engage in these acts of repetition. One of Picasso’s etchings – one that seems to speak most directly to the way the artist saw women – is Painter-jester painting on his model, who is making up her eyes (1971). As the title suggests, it shows a painter applying a brush to a model, as if it’s his strokes that are bringing her into being. No matter what he said, Picasso could never have shown all perspectives, and no matter what Gadsby says, I don’t think that he ever wanted to. These etchings in the Ludwig Museum, some of Picasso’s final pieces of work, show a man who was obsessed with himself; obsessed with his work; obsessed with history and what his own place in it might be. Decades later, we are still obsessed with Picasso, still haunted by him. I look forward to, in my own haunted gesture, writing these words again decades from now.