Shirin Neshat: “How much can we resist pain and torture? At what point do we break?”

12 min read

Iranian artist Shirin Neshat discusses her new film, The Fury, a fictionalised horror rooted in an even more horrific reality

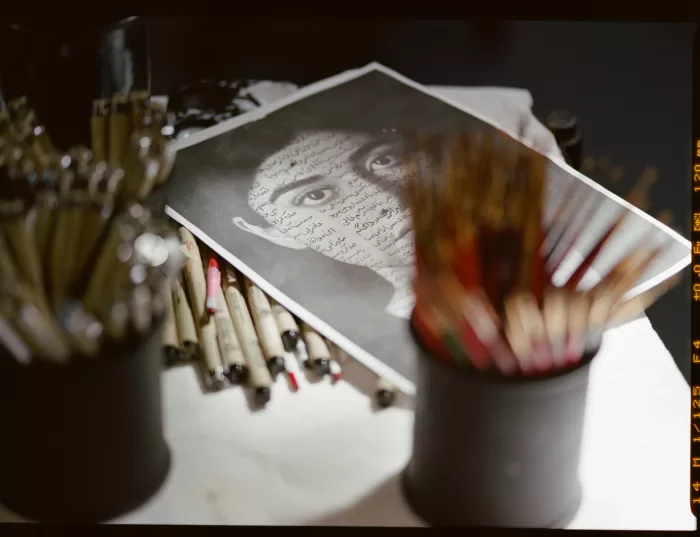

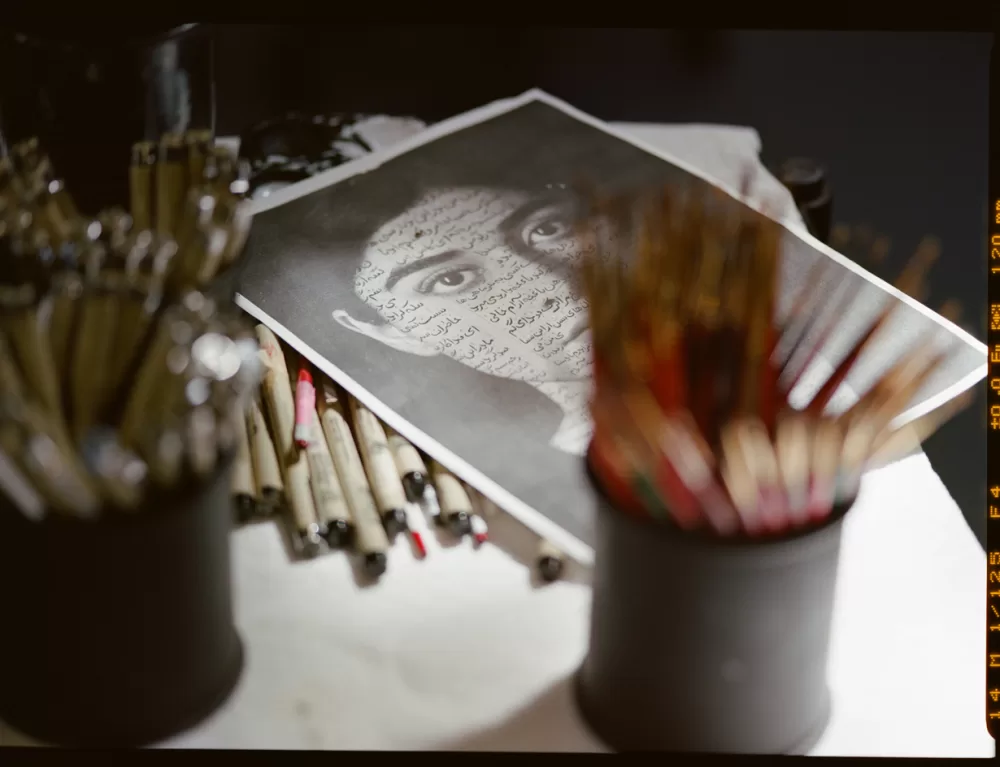

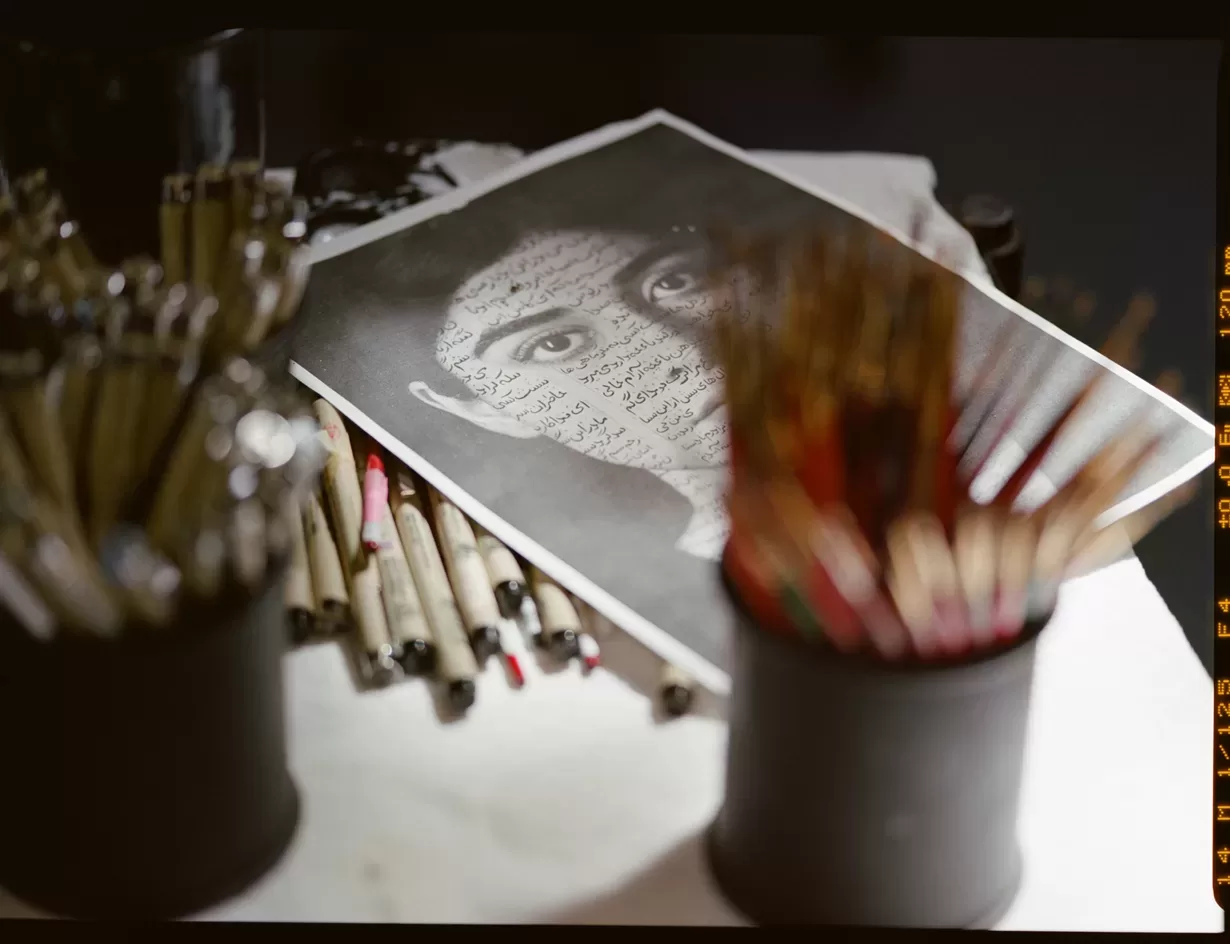

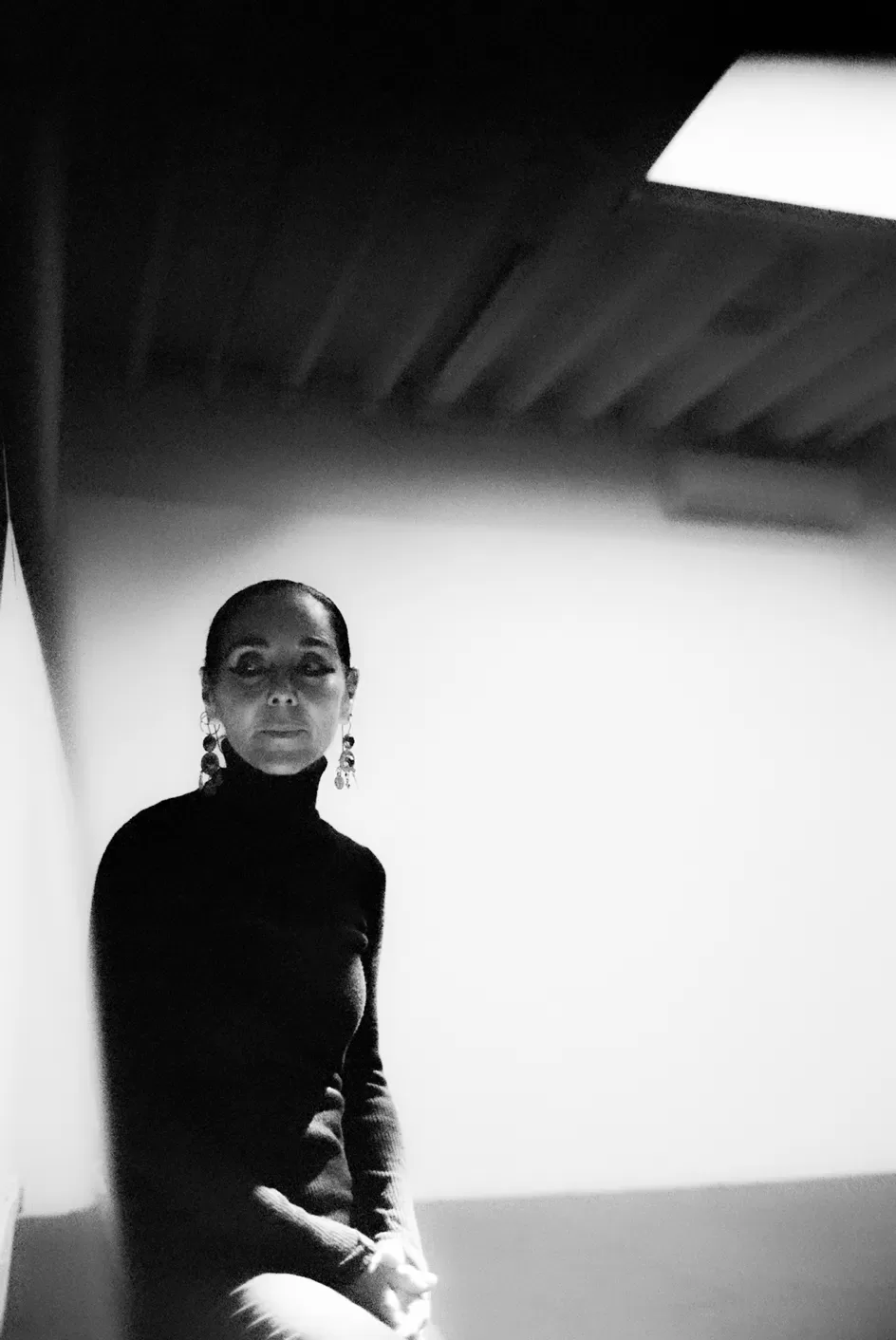

Shirin Neshat photographed in her Brooklyn studio

If you walk to the lower-ground floor of Goodman Gallery, London, between now and 8th November, you will be sandwiched in between two projection screens. On one, a military officer lights up a cigarette with menacing resolve. On the other, a young woman dances sensually in a ruffled Art Deco dress as the officer stares at her with dead-eyed lust. This is the opening sequence of Shirin Neshat’s The Fury, a fictionalised, stylised horror, rooted in an even more horrific reality.

“This work asks a lot from the audience in terms of understanding whose point of view they are looking at, and it’s constantly shifting,” Neshat tells me on Zoom from her studio in Bushwick, New York, her dulcet voice tempering the gravity of her words. “So you become a participant.”

Neshat was Born in Qazvin, Iran in 1957 to a middle-class, somewhat religious, somewhat liberal family. In 1975, she left her home country to study art in Los Angeles. Her plan to return was scuppered by the 1978-79 revolution and the subsequent diplomatic breakdown between the US and Iran. These were dark years for Neshat; burdened by the distant revolution and the horrors of the Iran–Iraq War; alienated by the increasing anti-Iranian sentiments in the US, and lacking the heart for her education.

It was not until 1990 that she went home, one year after the death of the Ayatollah Khomeini, (the leader of the Iranian Revolution and the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran). It was a very different country she had left behind, and the socio-political transformation was jarring. Her family, once cosmopolitan, were now under new rule and compulsory hijab laws. In 1996, Neshat returned to New York, where she has since lived in exile.

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

The idea for The Fury came to Neshat in 2021 on her daily dog walk through Bushwick. At the time, Neshat was “obsessively” following the trial of Hamid Nouri, a notorious prosecutor who was found guilty of playing a major role in the 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners. Neshat set out to create a film confronting the trauma political prisoners had faced, specifically women.

The Fury directly confronts sexual abuse. It alludes, though not explicitly, to the torture and assault repeatedly reported by female political prisoners by the Islamic Republic’s regime in Iran, and the trauma that lingers after their release. Neshat’s video follows the psychological and emotional journey of a young woman (played by Iranian-American actor Sheila Vand) who, although now living in liberation in the United States, remains haunted by her memories in captivity. The ethereal soundtrack is a version of the song Holm (‘Dream’), performed by the Tunisian singer Emel Mathlouthi. It was popularised in the 1968 film Soltane Ghalbha, but later became the anthem of Iran’s Woman Life Freedom movement following the murder of 16-year-old protester Nika Shakarami in Tehran last year.

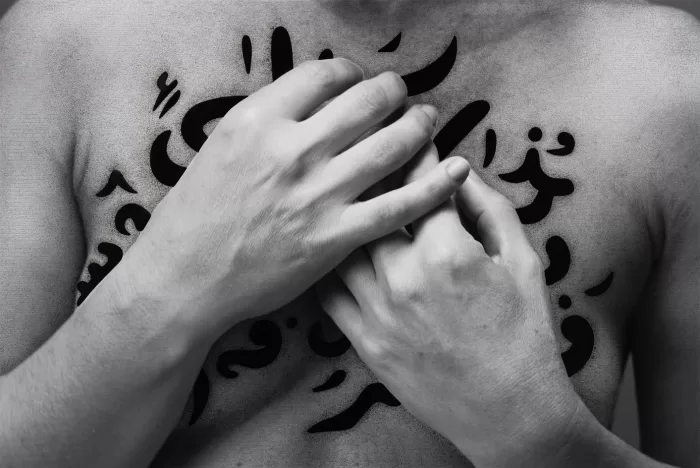

Neshat’s expansive work has long confronted the politics of the female body, as a symbol of shame and sin, and also a fraught battleground for religious and political ideology. “But the question of sexual assault and the female body as a space for violence wasn’t a subject that I explored,” she says. “My thinking process was about a woman who may be free at this point from prison, but is unable to disconnect from this very haunting past,” she says. “How much can we resist pain and torture? And at what point do we break?”

Neshat began shooting The Fury in June 2022, three months before 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in the custody of Iran’s morality police after she was arrested for violating the hijab law. “I think many people misunderstood because they thought I rushed to make this video, but I am not a ‘news artist’,” she says. “I’m not only talking about Iran, or to the Iranians, I’m talking to all women and to the entire world in terms of how we treat people who are incarcerated, particularly women who have far less power physically next to those who are guarding them.”

The film was shot in Brooklyn, two blocks from Neshat’s home. It loosely references two works of post-war cinema: Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) and Pasolini’s Saló (1975), both notorious for their eroticised portrayals of fascism. Although intentionally ambiguous in era, location and costume, The Fury also begins as seemingly post-war somewhere. “When you shoot in black and white, it tends to make anything timeless,” she says. “And there is something timeless about the relationship of power to women… I think there’s something about the ambiguity of time that allows you to relate to the story in a very different way.”

In another scene, the same woman dances again, this time in an unspecified warehouse. Neshat describes the location as “a place where you put your animals or somewhere beyond a prison; an industrial space where only bad things happen. It is a place of torture, it is a place of suffering and in an injecting pain.”

There, the woman is encircled by military men who gorge on her movements. She dances erotically, under duress, but at first appears unharmed. And then the bruises appear, and what agency and composure she had maintained, begins to rot away, transforming her from an object of desire to an object of violence.

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

In much of her recent work, Neshat has avoided portraying women as direct victims of oppression, and more broadly, avoided making overt political statements, particularly since Women of Allah (1993-1997). The photographic series, a potent commentary on contemporary Iranian society, violence and submission, depicts gun-bearing women wearing traditional chadors. “No matter how much I said, ‘these images are not supporting fundamentalism or fanaticism, they’re questioning them, not endorsing them’, people read it as if I’m celebrating fanaticism or the religious fervour that the government had promoted,” she says of the reaction to the series. “Or the government was thinking that I was criticising them. So it was impossible for people to look at the work just for its artistic merit.”

The Fury breaks the cycle; it doesn’t just evoke, it boldly confronts. “The most important thing for me was to have that emotional impact,” she says. “Mahsa Amini was a victim. We have victims and we have people who are powerless, and that’s why we who are free are able to fight their fight. It unleashes our rage.”

In the film’s final scenes, the woman has escaped captivity and returns to the streets of Brooklyn, almost naked and wailing. Passersby join her, scream with her, stumble behind her, dance in counterpoint to her agony; dance in solidarity; and tear up the streets in fury. This woman’s torture, now exposed to the light of day, provokes outcry. “It’s what happened with Mahsa Amini,” she says. “The minute she died, it provoked a process. And sometimes, unfortunately, it takes that to mobilise the people to understand that they share that injustice and that pain.”

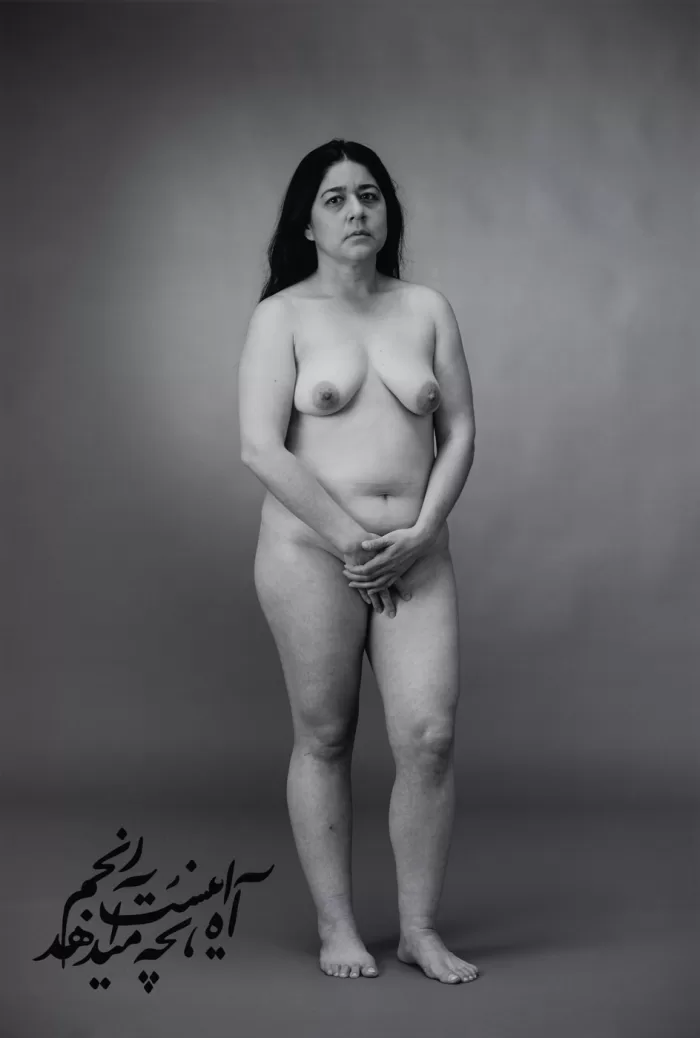

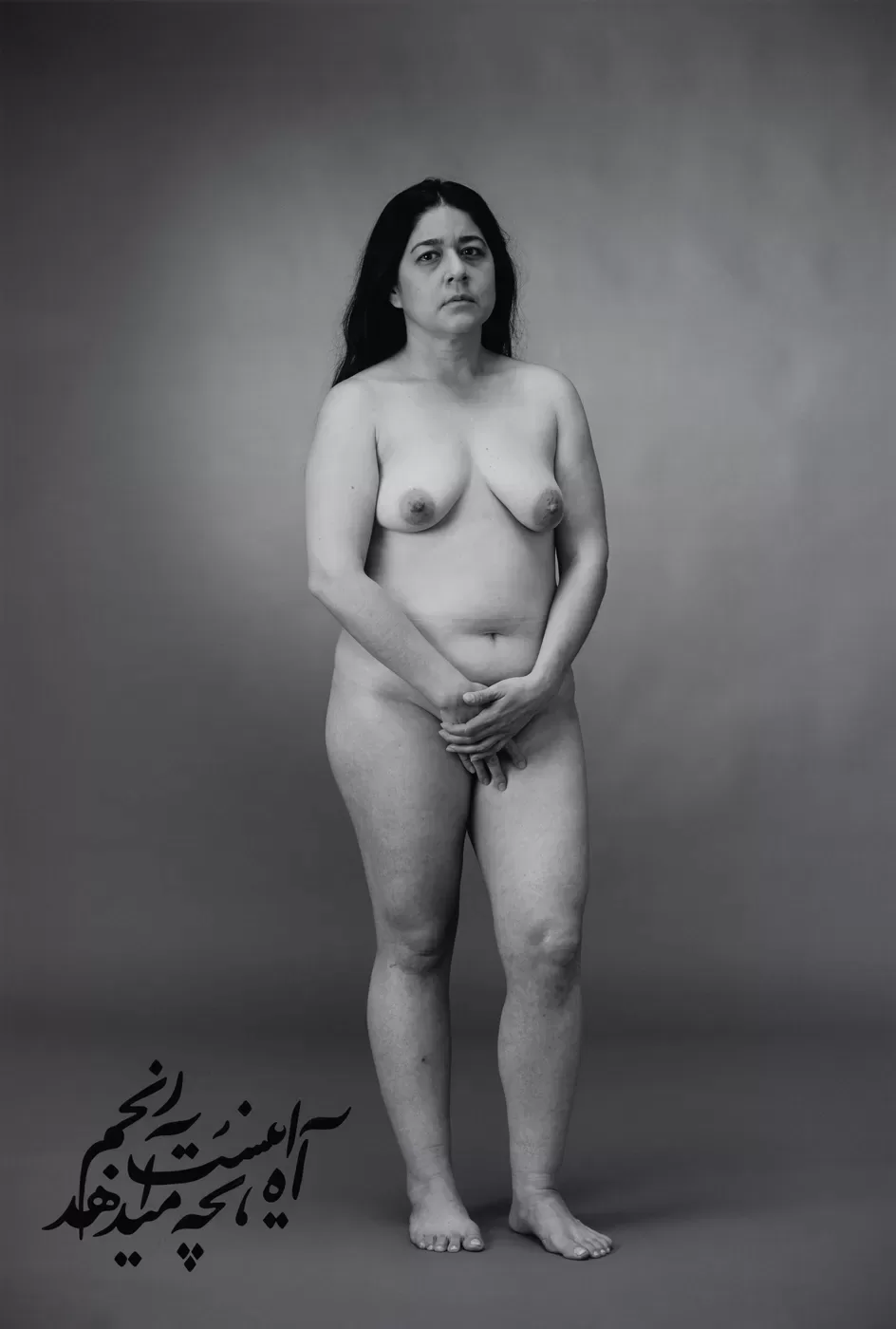

On the ground level of Goodman, Neshat presents a series of large-scale photographs. For the first time, her subjects are nude, and depict women of ethnicities, ages and body types. In some, there is a sense of empowerment and pride: “This is something that especially, as an Iranian Muslim woman, is the opposite of my experience”, says Neshat. “We were always feeling ashamed; that we were ugly, we were dirty, and we had to cover; we felt a lot of shame, and today, I carry a lot of this lack of comfort with my body.”

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

In others, shame and evidence of abuse are more palpable as women clutch at their bodies, hunch over and hide bruises. From a distance, the photographs look grainy. Edge closer and revealed, in microscopic detail, is Neshat’s signature hand-written Farsi script, based on the poetry of feminist Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad. “For me, calligraphy has never been just decorative. You can heighten the concepts and the emotions behind the images,” she says.

When The Fury debuted at New York’s Gladstone Gallery, Neshat recalled how the media were reluctant to publish images of the photographs, and the gallery put a disclaimer on the wall warning of violence and nudity. “It wasn’t even violence! She was never touched. But I could tell you that it provoked a lot of emotions in a good way, and also a disturbing way. And I think that’s something we need,” she says. “I didn’t have that much reaction in a long time about anything I did, I really touched a nerve.”

In London, Neshat is open to criticism about her show. “It could be very negative, it could be good. But it’s not going to destroy me,” she says. “As artists we mature, and we understand that you can win everyone’s heart and taste. You just have to keep believing in what you’re doing.”

Words:Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Photography:Cheryl Dunn

‘The Fury’ runs until 4th November at Goodman Gallery, London.

Until 22nd October, a 360 Virtual Reality version of the film will be screened at the 67th BFI London Film Festival as part of LFF Expanded.

The film will later be screened at GIFF – Geneva International Film Festival from 3-12th November.