What’s the point of a curator?

6 min read

These days, everyone’s a curator. So what do those with the actual job title do? Eliza Goodpasture explores

Being a curator is one of those classic dream jobs. Ask any wannabe cool girl or ambitious wearer of black turtlenecks what they want to be when they grow up, and they might say ‘curator’. But firstly, what is a curator? Secondly, aren’t we all curators now? We all know someone with a questionable dedication to curating a sparkling social milieu, a flawless Instagram feed and a capsule wardrobe. But the more mainstream the idea of ‘curating’ the minutia of our lives becomes, the more mystery surrounds those with the actual job title. What can they do that the rest of us can’t?

I’m fascinated by the proliferation of ‘curation,’ the idea of distilling, packaging and representing a large part of your life for the consumption of others. But for the purposes of this article, it’s also interesting to explore this strange coopting of an art world term. The verb ‘curate’ came from the word ‘curator,’ which shares its roots with the word ‘care.’ Since the 17th century, ‘curator’ has meant the keeper of a museum collection. Modern museums like the National Gallery and the Louvre were born in the early 19th century, and so were modern curators – the Victorians continue to haunt us.

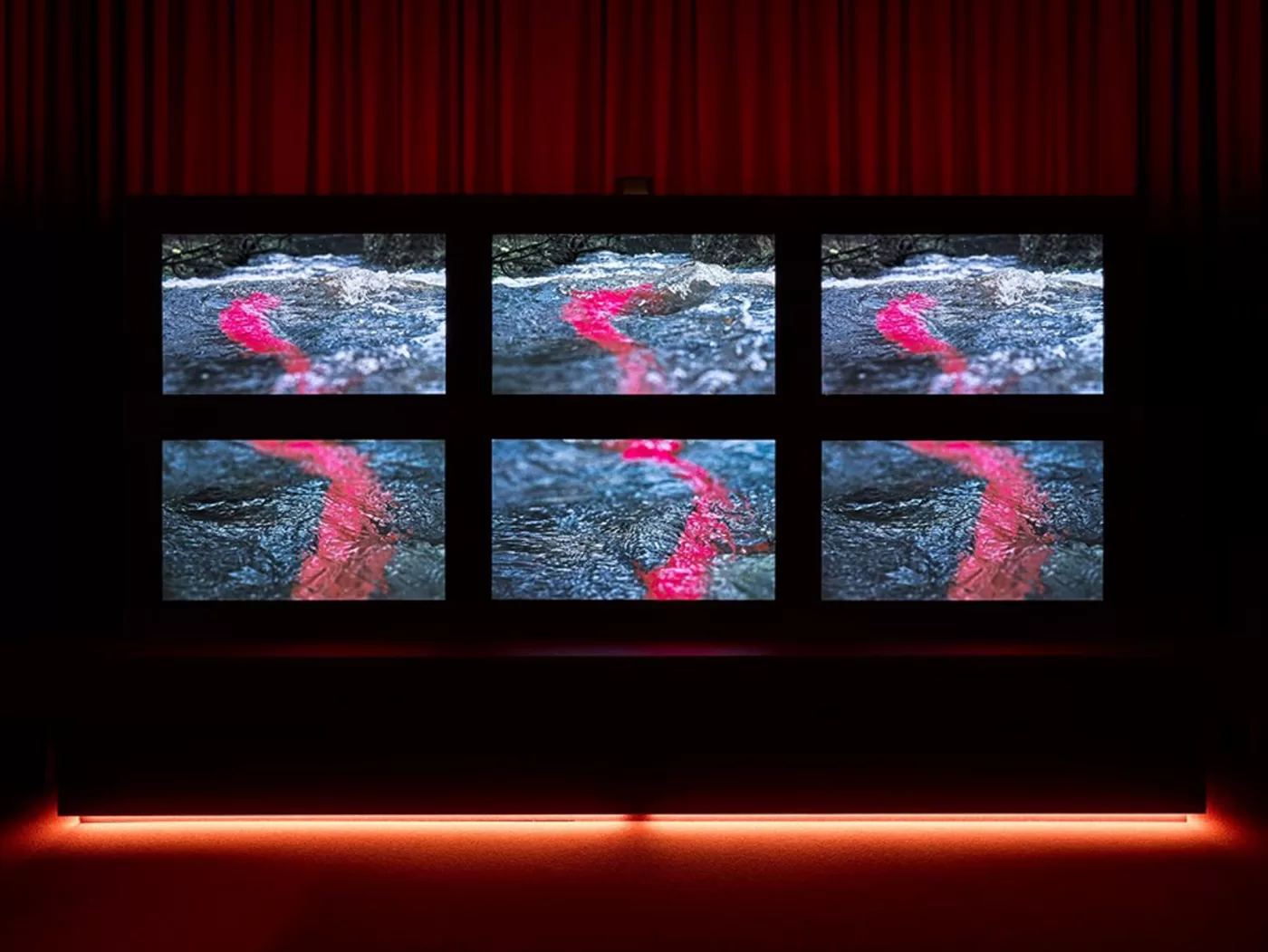

John Akomfrah, Listening All Night To The Rain, British Pavilion, 2024. Photography by Jack Hems

There are many ways to be a curator of art. Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine and author of Ways of Curating, amongst other things, has become something of a spokesperson for the profession. He describes the four tasks of a curator as preserving existing art, selecting new art, connecting the old and new to art history, and the act of physically putting everything in the gallery space. His ethos of active curating has arguably fueled the rise of the general public’s awareness of ‘curating’ as an idea. Being a curator requires a wide and deep understanding of a subject, often many. The role is to encourage viewers to not just see, but to interpret art. You may have noticed that intellectualism is not exactly in vogue at the moment (see: the constant denigration and defunding of the humanities, the international rise of populism, the algorithmic flattening of culture online, etc.). It’s easy to say, “Hanging stuff on the wall? I could do that!” and forget about the time it takes to place it just so in relation to the canon of art history, and everything else in the room. Curators are the mediators between the art and the public, the tastemakers, the stewards, the storytellers.

“It’s essentially a conversation with an artist,” is the way Tarini Malik put it. This year, she curated John Akomfrah’s British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, an ambitious seven-room video and sound installation that grapples with the political legacies of contemporary Britain. For her, a curator is a mediator, constantly balancing “being in service to an artist but also in service to your public.” Sometimes, the two can pull in opposite directions. A key question she kept returning to was: “What is it that we want to dismantle?” It frames curatorial work as an act of taking apart to reassemble into something new, rather than the preservation synonymous with institutions like the National Gallery or the British Museum.

View this post on Instagram

Working with a living artist can make curating a collaborative partnership, but what do you do when the artist is dead? Curators of historic shows have a different set of stakes and responsibilities. A huge part of their job is the ‘care’ root of curating: collections care and conservation. It is also fraught with different kinds of logistics, including navigating estates and inheritance, negotiating loans with both public and private collections to get art in front of the public, and cultivating institutional reputations – to say nothing of the quagmire of interpretation. “My job is, in a way, to explain where contemporary art comes from,” Melissa Gustin explained. “It didn’t just happen, and we need to give the public that context.” Gustin is the curator of British art at the National Museums Liverpool. She laughed when I asked her about the stuffy reputation of museum curators. “Not to get all ‘those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it’, but you know, someone has to look after it,” she replied. “We’re very conscious of trying to use the pillars of the institution to uplift new stories.”

The dismantling that contemporary curators like Malik are often focused on is only necessary because of the inertia of many institutions, stuck in the rut of choices made by curators decades ago that omitted historical context, geographies and often exclude artists who are not Western, white and/or male. But as Gustin explained, change can happen from within the institution as well. Rehangs of permanent collections to offer a more balanced view of history have received a lot of attention in the past year. As the very mixed reviews Tate Britain’s rehang got last year prove, it’s a complex task for a curator; you will never please everyone, but you can at least show them something new.

The new main entrance hall at the National Portrait Gallery, London featuring Reaching Out by Thomas J Price (2021), Nelson Mandela by Ian Homer Walters (2008) and Louise François Roubiliac attributed to Joseph Wilton (1761). Photograph © Gareth Gardner for Nissan Richards Studio

This spring, Rebecca Birrell curated the Fitzwilliam Museum’s rehang in Cambridge, which opened to rather less fanfare. Birrell decided to organise the galleries thematically, not chronologically. She hung contemporary paintings alongside much older works, prompting us to make new connections – and to notice whose stories are not told. Some people might argue that a good curator is invisible, but I wouldn’t. I love a chunky exhibition where the curator has a clear thesis. I want to be reminded that truth and taste are not fixed.

Curators are dangerously invisible. If we never see them or talk about them, they are neither credited nor accountable for what we see. Maybe we should all pay a little more attention to the way a wall text is written or the way a drawing is hung. Notice how you are being steered to understand a work, and decide whether you agree or not – that’s what keeps the conversation going.