Yoko Ono: an artist for our times

7 min read

For decades, she was known as ‘the artist who broke up the Beatles’, but ahead of a major show at Tate Modern, Milo Astaire – Plaster founder and diagnosed Beatles superfan – reflects on how the world is finally catching up with Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono, Half-A-Room, from Half – A Wind Show at Lisson Gallery London Photo by Clay Perry © Yoko Ono

They broke up because ‘Yoko sat on an amp’. It was always Yoko who took the blame… Her name has even become a verb for tearing a friendship group apart… ‘She’s doing a Yoko.’ It was Yoko Ono who brought about the end.

Of course, it wasn’t anything to do with McCartney’s disdain for the Machiavellian music manager Allen Klein who had turned the other three against him, or John Lennon’s desire for a “divorce” from the band, his obsession with having Yoko as part of the recording sessions, or George Harrison’s growing frustrations at being overlooked, on his way to a career zenith. No, it was all down to Yoko.

It’s a collective belief that has been held on to for too long, unquestioned. People don’t feel the need to delve deeper. Pick up any modern-day Beatles academic journal (yes, there are quite a few out there), and you can plainly see that she wasn’t the root cause of their separation. Life is grey, not black and white. Yoko was an easy target, she was viewed as an outsider, a viewpoint exacerbated by the revolting stream of racism directed toward her by the UK press at the time. After all, she was different: she was married twice before, she was from Japan (the war had only ended twenty years ago), and her grasp of English wasn’t perfect.

Installation view of ‘PEACE is POWER’, first realised 2017, in ‘Yoko Ono: The Learning Garden of Freedom’ at Fundação de Serralves – Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, 2020. Photo © Filipe Braga

There are some claims, most explicitly in the semi-authorised Paul McCartney biography by Barry Miles, that Yoko had reached out to McCartney a year before in 1965 to gather song manuscripts for a book she was completing. Yoko first came into public consciousness after she met Lennon at the Indica Gallery in 1966. Their meeting arose when Lennon stumbled upon Yoko’s performance, Ceiling Painting/Yes Painting in which she invited audience members to climb a white ladder. On the top step, they’d find a magnifying glass hanging from the ceiling on a metal chain; when viewers looked through the magnifying glass the word ‘yes’ appeared on the ceiling. The legend goes that John was so amused by the absurdity, that he asked the gallerist John Dunbar for an introduction to Yoko. It was the simple phrase ‘yes’ in a world submerged in negativity that was so refreshing for Lennon. Over the next year, they fell in love, with Lennon leaving his then-wife Cynthia.

Yoko is an artist who has always been misunderstood. Though so often a target of hate, she has spent a career attempting to bring joy and hope to her audience; a sentiment that will no doubt be at the forefront of her major upcoming Tate Modern, ‘Music of the Mind’. Her book Grapefruit, published two years before she met Lennon was a collection of instructions aimed at helping audiences create art through their imaginations and set their minds free. It is a book full of positive imagery and spiritual guidance. So how has someone who is seen as such a destabilising figure in pop culture mythology stayed so steadfast in her message of positivity?

Installation view of Apple 1966 from Yoko Ono_ One Woman Show, 1960-1971, MoMA, NYC, 2015. Photo © Thomas Griesel

Yoko Ono, Freedom 1970. Courtesy the artist

Another performance, Cut Piece also underlies that she is far from the counterculture; hippie messaging of 1960s utopian ideals. In 1964 during a performance in Kyoto, Japan she invited people to cut off parts of her robe until she was left in just her underwear. It was an act of early feminism, of allowing an audience to take what they want, but born from a desire to give to the world, and to implore others to give. It was this piece that Marina Abramović would take huge inspiration from some ten years later in Rhythm O.

Then there was the iconic bed-in for peace that Lennon and Yoko staged on their honeymoon in 1969, where they stayed in bed for a week at the Hilton Amsterdam in an effort to promote peace through non-violent protest. So long assumed to be Lennon’s genius, it was in fact Yoko who was the driving force. She recognised the platform she had been given, and through her collaboration with John, sought to make the world a better place. Of course, some works landed better than others. Self-Portrait, a 42-minute film depicting Lennon’s semi-erect penis, premiered at the ICA in 1969. But the world wasn’t ready, and the film was never shown beyond its first screening.

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece 1964 Performed by Yoko Ono in “New Works by Yoko Ono”, Carnegie Recital Hall, NYC, March 21 1965. Photo by Minoru

Yoko’s life has always be defined by her relationship with Lennon. It is what first brought her into the public eye, with recognition unfathomable to almost everyone on the planet. But it is her art, and her unique worldview that has secured her legacy. For a person who has been the victim of vitriol by Beatles fans the world over for so long, her unwavering optimism is remarkable. It was Yoko’s words in Grapefruit that influenced the bulk of the lyrics to Imagine, a song synonymous with peace and love.

Yoko Ono is one of the great artists of our time, whose life and work have been tirelessly dedicated to uniting a fragmented world. With the planet more divided than ever, Yoko’s art feels more important than ever. And I hope that we can finally lay to rest the fact she didn’t break up the Beatles.

Yoko Ono, Film No. 4 (Bottoms), 1966. Courtesy the artist

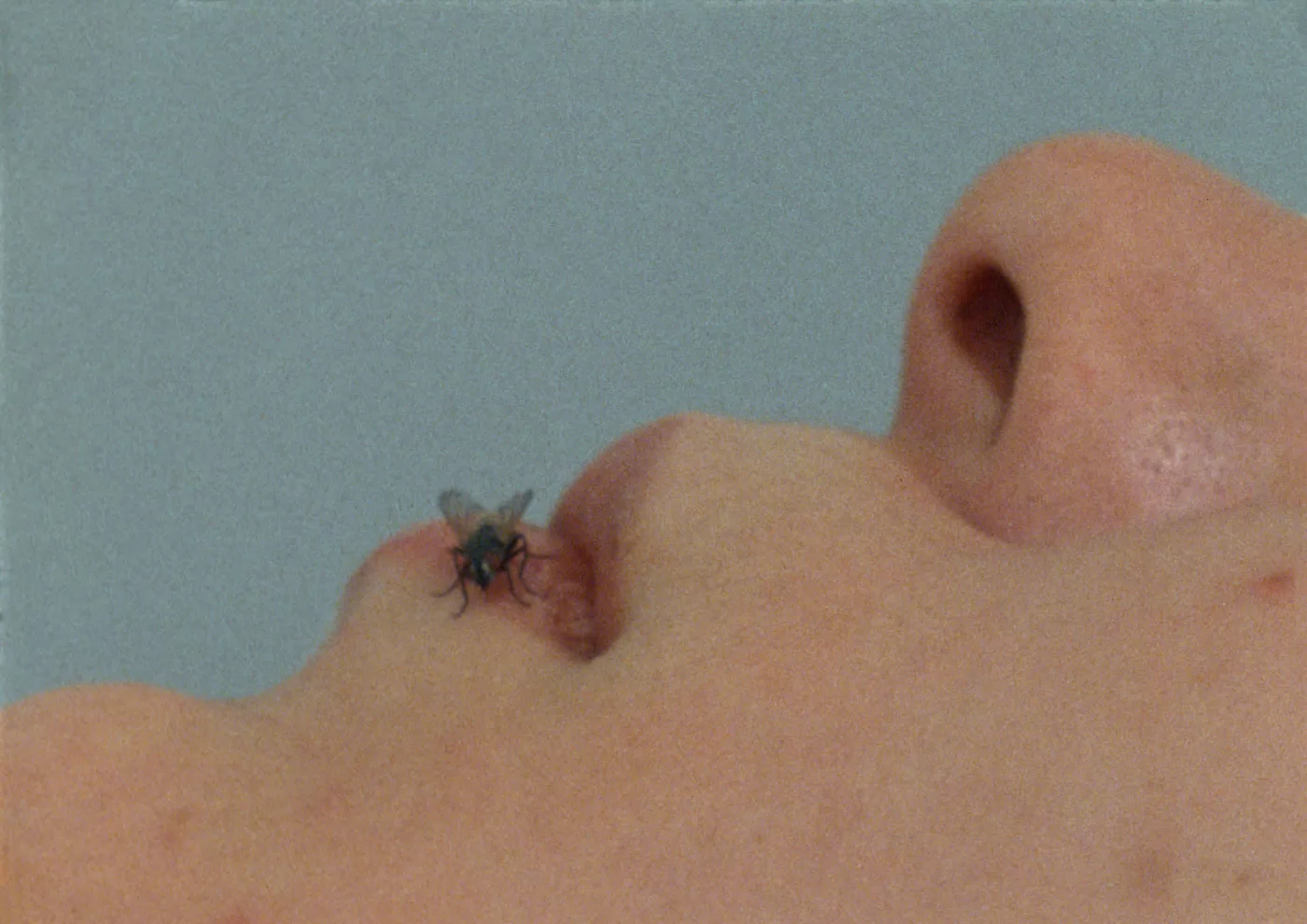

Yoko Ono, Fly, 1970. Courtesy the artist

Yoko Ono: ‘Music of the Mind’ runs until 1 September 2024 at Tate Modern. tate.org.uk