Ex Libris: Jonah Freud on Michael Landy’s Break Down

0 min read

Jonah Freud reflects on sentimentality and the annihilation of worldly goods through Michael Landy

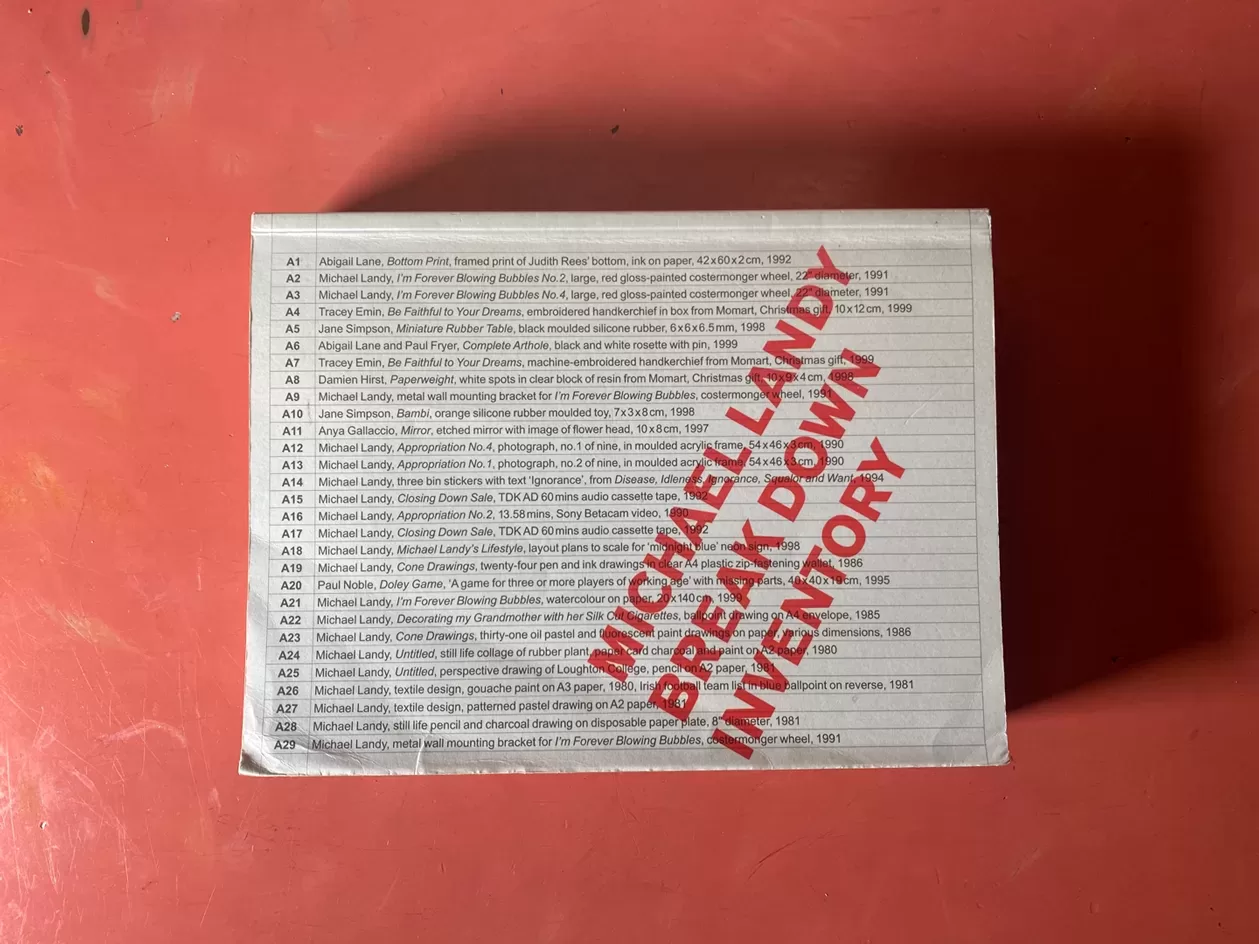

Page from Michael Landy’s Break Down Inventory, 2001, where over 5,000 individual items have been catalogued

On the morning of 10th February 2001, Michael Landy owned a total of 7,227 objects. 14 days later he owned nothing but the clothes on his back and 5.75 tonnes of powdered consumer and personal goods, neatly packed in individual plastic bags.

In the book world, I often visit the house of someone who has recently passed, on the request of a widowed partner or child, to look at their collection with the view to potentially purchase the books, or at least give a rough valuation of the shelves. It’s a strangely intimate process: I’m left for a few hours in a room with substantial bookshelves, stacked with a lifetime of literature. In the process, I quickly realised that I often look at these collections not as books but as portraits of a person, painted themselves one purchase at a time; the decades of their life abstractly represented in the wear of the spines (or lack thereof), the yellowing of the pages and the obscure themes that emerge through the shelves. The experience of going through Landy’s books is the same as this experience, just condensed, amplified and formalised.

Cover of Michael Landy’s book, Break Down, 2001 – part manual, part inventory, part research file

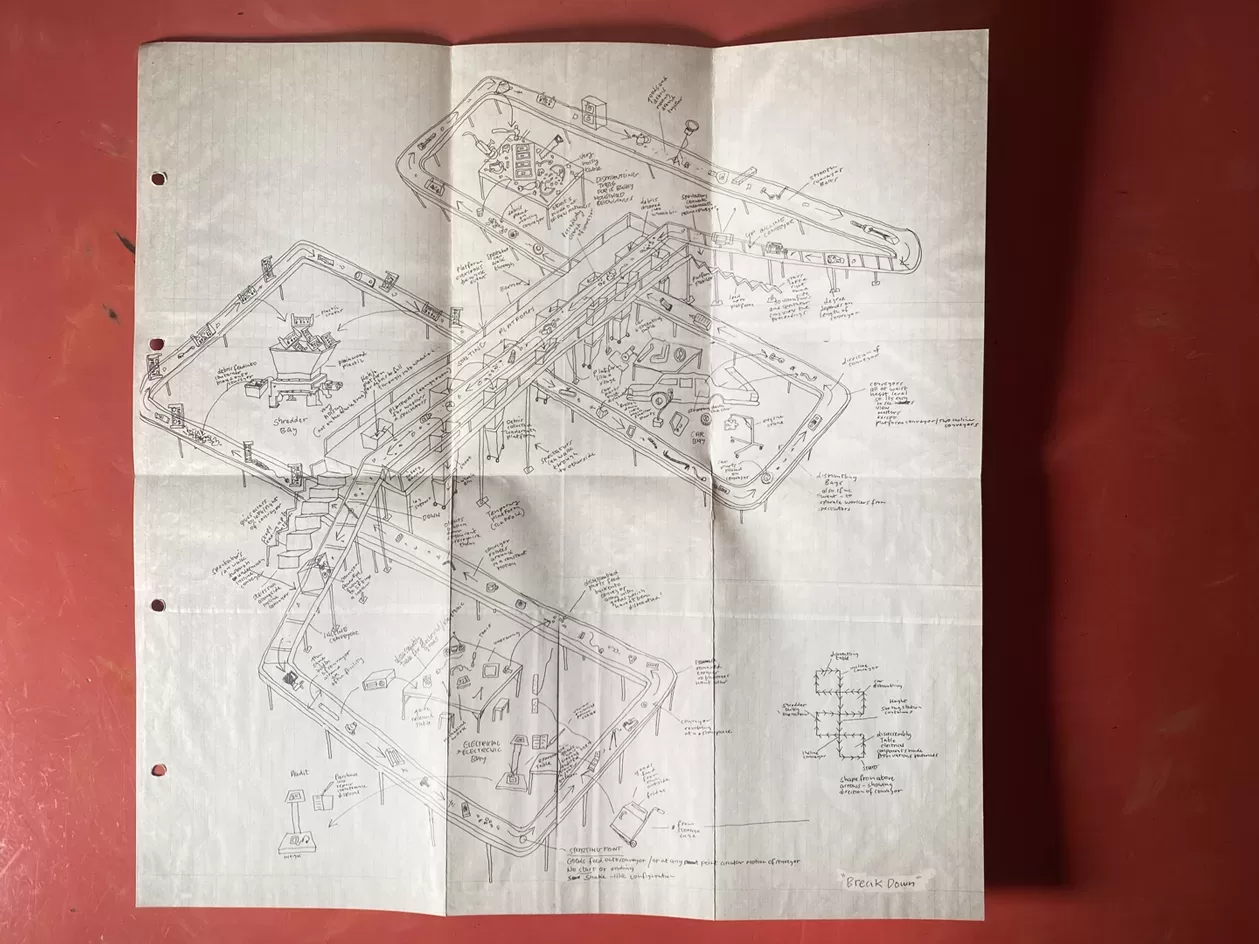

In a vacant storefront on Oxford Street, Landy and a team of technicians, mechanics, assistants and artists loaded up everything he owned – artwork, clothes, family heirlooms, love letters from Gillian Wearing, his Saab 900 Turbo – onto a specially constructed conveyor belt and began a two-week process of ‘breakdown’. Each object was disassembled, stripped into component parts, and then pulped and powdered, with each step rigorously and scientifically documented, marking down individual weights and values of each material and component in the objects. It is an artwork with no tangible end product save for two books, Break Down and Break Down Inventory, strange and unartistic works for a strange and singular performance that remains in my mind one of the landmark works of British art and one criminally under-considered.

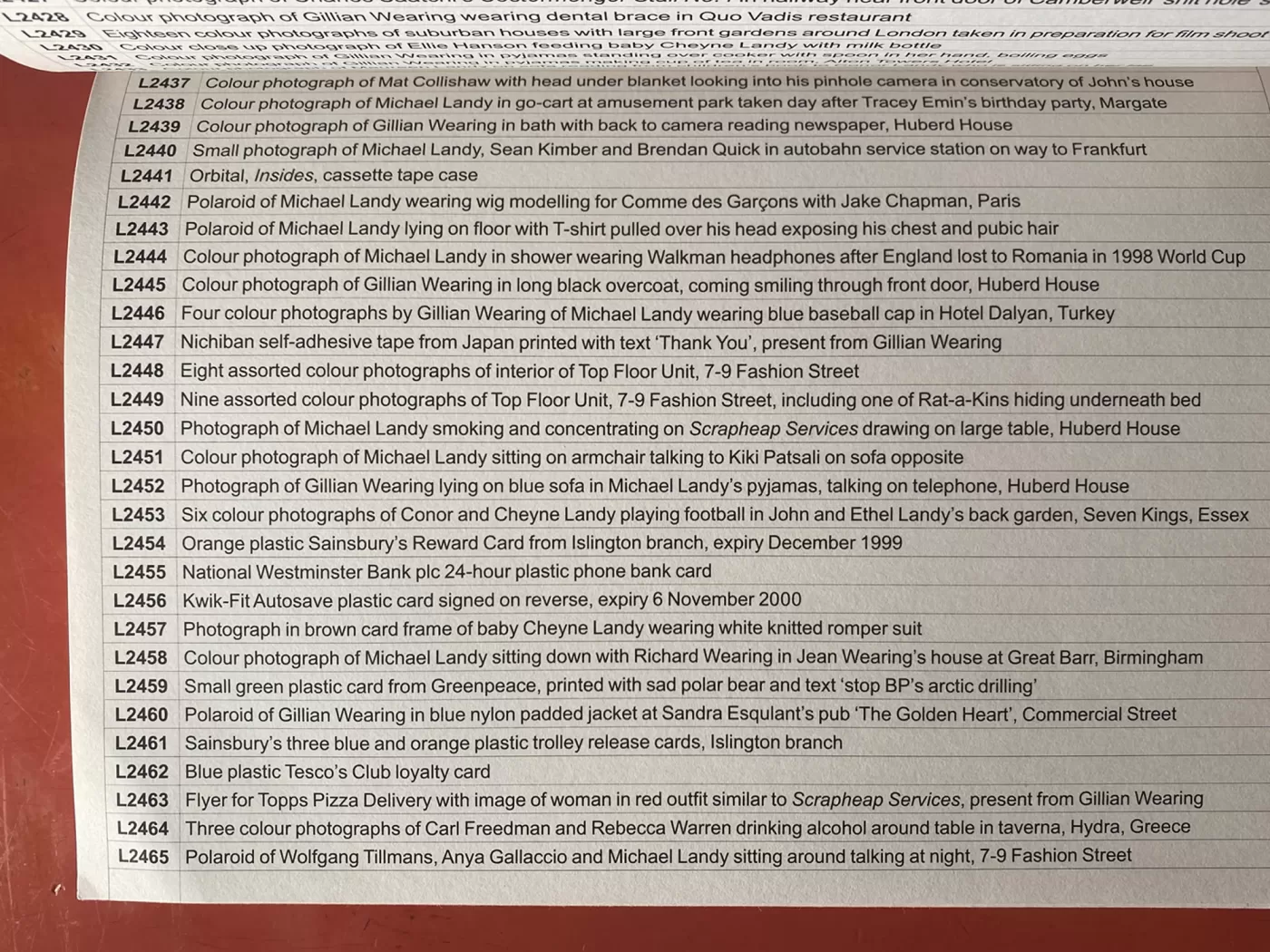

Break Down Inventory makes no reference to destruction; it is exactly what it says on the tin. Inside are 300 pages of what amounts to an Excel spreadsheet of every single object Landy owned, with very little additional information; only the object, occasional provenance, vital statistics and necessary consumer specifications.

Landy’s inventory offers an obsessively detailed portrait of a single man. You learn about his music taste, fashion sense, art practice, collections and obsessions. You see glances of the scraps of paper he held onto for 30 years, either through sentimentality or laziness, the contents of his studio, his pantry and his bedside table; mundane objects that suddenly feel poignant in the face of imminent destruction. It’s hard to flip through it without considering your own possessions, and how much of who we are is defined by them. Break Down is a consideration of a consumer culture, of disposability and planned obsolescence. Nothing is built to last forever, Landy says – he is just speeding up the process. A man plays god to strip himself of earthly goods. Yet by keeping a record, Landy doesn’t destroy anything. The version of himself created through his ownership still exists in the pages of these books. It matters not that his father’s sheepskin jacket now lies as dust, buried in a landfill alongside a degrading leaflet offering a £15 discount voucher for selected Argos products. It exists within the inventory and thus it serves the same psychological, if not physical, function. The inventory of Landy’s breakdown is an inventory of Landy’s person, detached from physicality but not association.

Break Down, the companion piece to Inventory is a different beast altogether. A translucent ring binder with clearly demarcated sections, it is an artist’s book-cum-destruction manual. There is a staunch detachment in the writing. Landy takes the emotion out of his destructive act, presenting his research, his process, ideation and execution like guidelines for a science experiment, or an employee handbook at a multinational conglomerate. There’s no sentimentality about the objects he’s destroying, save for a brief moment of slippage over his car. The Saab 900s has its own zone in the Break Down production, with destruction overseen by Saab mechanic Dave Nutt who seems to become the sole, transposed object of Landy’s sentimentality and grief. Landy talks about him lovingly and he seems obsessed with his last name. The sentimentality he works to distance from his possessions, he lets slip when it comes to Dave.

Break Down Inventory catalogues 5,000 individual belongings

Fold-out page from Break Down, resembling an instruction manual

The third section of Break Down is titled ‘Selected Possessions’ and is the most intimate section of the entire work. It features naive, childlike line drawings of a variety of objects: a fridge magnet from Alton Towers, a drawing of a drawing for his wife, dry skin lotion and two pages dedicated to every angle of his car. Landy worked to mechanise the process of Break Down, to remove any humanity from the objects he owns, perhaps to make their destruction easier to bear. But in these drawings, it is impossible not to see objects as extensions of ourselves. The tatter that fills up our lives has meaning, whether we want it to or not. Next to a delicate line drawing, in scratchy handwriting, are the words “No Bite Mosquito Killer which ive never used ive had it since 1984.”

We all have a ‘No Bite Mosquito Killer’ of some sort; its absence would probably go unnoticed, and unfelt. But pile 7,227 of these objects together and suddenly something is lost. Landy wanted to bring our attention to a mass consumer culture and in turn, criticise the world. Yet, perhaps the most poignant emotion the books create in me is a deep sadness at the loss of a plug-in pest deterrent. Break Down is staggering work, and the books communicate it beautifully, but they also add a new element as truly great artist books so often do. Landy pulls back the curtain of a sterile, cold-blooded operation, letting slip the emotion the performance tried to hide if only you look close enough.

Break Down features a montage of images of the artist’s belongings