Perron-Roettinger thinks outside the box

12 min read

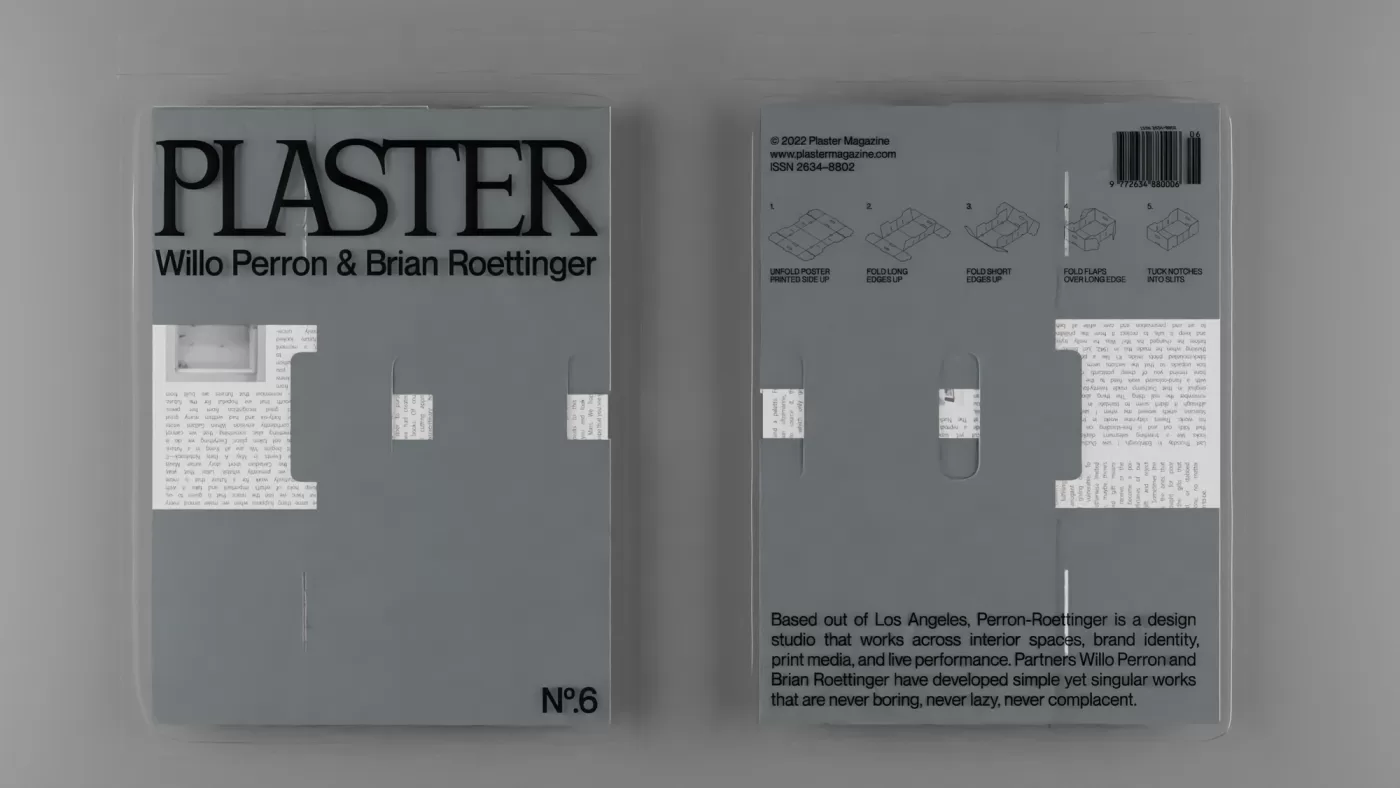

Plaster Issue. 6 was a collaboration with leading design studio Perron-Roettinger, who reimagined the utility, innovation and capacious symbolism of the box

When Christine Therese turned eight, her father bought her a wooden box of paints and a palette. From an early age she made marks, marks on the canvas, chalk circles on the tarmac. Her favourite colour was ultramarine, the costliest colour in the world. Even Michelangelo couldn’t afford it. When the great master wasn’t able to source it, the painting went unfinished. Christine Therese began using these paints with the earnestness of prepubescence, which only grew into her teenage years when she received perfect marks in her drawing classes. As soon as the time came for those her age to commit to decisions about their further education, the art teacher at her gymnasium came to her house to speak with her father to attempt to convince him to send his daughter to art school. Her father, Christine Therese recalled, wouldn’t be taken in: “She will go to art school if she feels like it.” But for her, attending art school was out of the question. A few art schools were nearby, the closest in Roskilde, and she had older friends who had attended them. She was, she says, disappointed in the work they made there, feeling that the schools taught them the “craft, but not the art.” Christine Therese last used the paints on a strange November afternoon, one of those grey days where the hours seem to drag and stall, when the weather was warm for winter and cold for autumn, and she put all the tubes in the box and shut the lid tight.

The Velvet Underground’s ‘The Gift’ tells the story of the lovesick and naïve Waldo Jeffers who is in a long-distance relationship with his college girlfriend Marsha Bronson. When they go back home for the summer – Waldo to Locust, Pennsylvania; Marsha to Wisconsin – he is consumed by jealousy. Waldo’s convinced that she will be unfaithful. He can’t afford to fly and visit her, so instead he decides to mail himself in a large cardboard box. The plan is simple: when he arrives at Marsha’s apartment, in the large cardboard box, he will jump out, surprise her, and confess his undying love. He gets shipped on Friday, delivered on Monday. When that day comes, Marsha and her friend Sheila are talking in the kitchen when the package arrives. Marsha had been telling Sheila about her one-night stand with a guy called Bill the evening before. Waldo had done such a good job taping the box shut the two women struggled to open it, until Sheila decides to take out a sheet metal cutter from Marsha’s basement and inadvertently stabs Waldo straight through the head, causing ‘little rhythmic arcs of red to pulsate gently in the morning sun.’ I’ve been thinking about the idea of gifts lately, and the convention of wrapping something in something else to ensure it is kept a surprise until the moment of revelation. I’m sure Waldo didn’t want to send himself in the mails just to save money. He yearned to see Marsha’s face light up when the box she didn’t expect, the box she couldn’t remember ordering, had him inside. Is there anything more fulfilling than believing oneself to be a gift to others? It’s a rather arrogant notion, sure, but there’s something humble in it, too: the idea of giving oneself over without any expectation of reimbursement. To arrive vulnerable. To jump out of the box knowing that the room might not have otherwise invited you into it. But maybe we always expect something in return, maybe there’s never a pure gift. The other day, I learnt that the word ‘gift’ means poison in German. We can never be sure that the gifts we receive, or the giving of ourselves to another, will remain a gift and not become a poison. Sometimes the beneficiaries of our gifts will spurn that gift and reject it like a cup of hemlock. Sometimes the gifts we love the best are the ones that kill us. So spare a thought for poor Waldo Jeffers and all the gifts that get declined, or ignored, or stabbed through cardboard and bone, no matter how wonderful we believe them to be.

Last Thursday in Edinburgh, I saw Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-Valise, or the box in a suitcase, up close. It looks like a travelling salesman’s display case. There’s this delicately cut yet super tough leather that folds out and is free-standing on four panels, each of which include a reproduction of one of his works. There’s sixty-nine works in total, mostly of paintings. I look at ‘The Nude Descending the Staircase’, which wowed me when I saw it as a teenager in Philadelphia, although it didn’t seem to translate in miniature. Few things do when you remember the real thing. The thing about La Boîte-en-Valise is that it’s an original in that Duchamp made twenty-four deluxe versions of the case, each with a hand-coloured work fixed to the inside of the lid, but the reproductions remind you of cheap postcards outside a country train station. The box unpacks so that the sections seem to slide out, with other folders and black-mounted prints inside. It’s like a portable museum. What was Duchamp thinking when he made this in 1942, just before he moved to New York, just before he changed his life? Was he really trying to pack everything away and keep it safe, to protect it from the philistines? Was this his monument to art and preservation and care, while all behind him lie the desecrated bodies and the burnt books strewn in the central squares? The truth is I’ve never seen Duchamp as a pure ironist. Great chess-players seldom are.

HOW TO SEND A PARCEL WITH FEDEX

- Identify your shipment. Refer to the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) for the correct identification, classification (including UN or ID number), Proper Shipping Name, hazard class and, if applicable, subsidiary hazard and Packing Group.

- Package your shipments correctly. Some dangerous goods have specific packaging, labeling and marking requirements, and may require a completed Shipper’s Declaration for Dangerous Goods form. For information on the proper shipment preparation for IATA and ICAO shipments of nonradioactive items, go to images.fedex.com/us/services/pdf/DG_Job_Aid.pdf

- Protect yourself. Shippers who do not prepare their packages according to IATA and ICAO regulations can be fined by federal and civil authorities and may even face criminal prosecution and imprisonment. The government requires people to be trained and certified to handle and prepare dangerous shipments. FedEx conducts training seminars throughout the year. To view schedules and register for a seminar, go to fedex/ registration.meetingevolution.net

- Ask us for help. The FedEx Dangerous Goods/Hazardous Materials Hotline is prepared to answer your questions on the proper preparation of dangerous goods for shipment in the FedEx Express® network. Call 1.800.GoFedEx 1.800.463.3339 and press 81 or say “dangerous goods” to speak to a dangerous goods shipping specialist. In non-US locations, contact FedEx Customer Service and ask to speak with a dangerous goods specialist.

Akira Yoshizawa (1911-2005) is credited as the inventor of modern origami. The son of a poor dairy farmer, he moved to take a factory job in Tokyo when he was just thirteen. By his early twenties, he was promoted to the position of technical draughtsman and taught his younger colleagues the mathematical principles of geometry. He soon decided to leave the factory and spent some twenty years in near poverty selling tsukandani door to door to pursue making origami full-time. According to his own estimation made in 1989, when he was nearly eighty, Yoshizawa had created more than 50,000 models, of which only a few hundred designs were presented as diagrams in his eighteen books. Of course, origami has been practiced in East Asia for hundreds of years, but Yoshizawa erred from the traditional cutting approach and developed a wet folding technique which rendered softer and more naturalistic lines. It’s extraordinary how his origami sculptures, mostly of animals, can communicate complex emotion: the way the curved wrist of the gorilla rests on the ground, at once stabilising himself and expressing resignation; the arched back and dainty hind legs of the fox, poised to take flight; the irrepressible hunger of the baby sparrows, in miniature folds replicating their mother, desperate for food. Folding paper might seem like an outdated way to make art. But all the best art relies on a simplicity of form, of the weight of the composition being properly balanced for an object to become capable of telling us something about our own lives. Yoshizawa was an ordinary man who loved origami. It was his joy and his redemption from the drudgery of what the world promised him at thirteen. Yoshizawa was also extraordinary, not because he was eventually awarded, in 1983, the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito, one of the highest honours that can be bestowed on a Japanese citizen. No, it was because he fucking loved origami.

Maintained over centuries, the sanctuary of the university was non-negotiable in Paris until the 1968 riots. Those revolts started when the Rector of the Sorbonne, Monsieur Jean Roche, invited the police onto campus. It proved an unconscionable error of scholarly judgement. The students couldn’t imagine cops roaming about and maybe arresting them, so they spontaneously linked arms and streamed up and down the Latin Quarter and made barricades. They fought the police, who won of course. No one died, although hundreds were hospitalised. But when Premier Pompidou returned from Afghanistan, he promised to meet the student’s demands. Around the same time, in the summer of 1968, Joseph Beuys made a work of art that he called an ‘intuition box’, or a small box made of spruce wood, which included 12,000 objects. He signed each one. Boxes, like riots, can be spurred by intuition, by something that does not require conscious reasoning. When Beuys made his boxes, I cannot help but imagine him thinking about all the possibility that each one contained, that he was making a space for something radically unforeseeable to take the place of his objects. The same thing happens when we keep those old cardboard boxes in the spare room, the really broken and battered ones from when we moved house, folded and kept out of sight for the next time they’ll be taped up and be filled with something else. The same thing happens when we make almost every decision in our lives: we use the space that is given to us, we try to keep hold of what’s important and take it with us, we look to intuitively work for a future that is more free than the one we presently inhabit. Later that year, in September 1968, the Canadian short story writer Mavis Gallant published ‘The Events in May: A Paris Notebook—II’ in The New Yorker. It begins: ‘We are all living in a future, in something that has not taken place.’ Everything we do is a preparation for something else, something that we cannot properly foresee or confidently envision. When Gallant wrote these words, she was forty-six and had written many great stories and achieved great recognition from her peers. It’s not only the youth that are hopeful for the future, and it’s important to remember that futures are built from intuition as much from foresight. Beuys knew that well, and when you consider the ‘intuition boxes’ in relation to their moment, a moment when the future looked so precariously uncertain yet buoyed by hope, they contain multitudes.

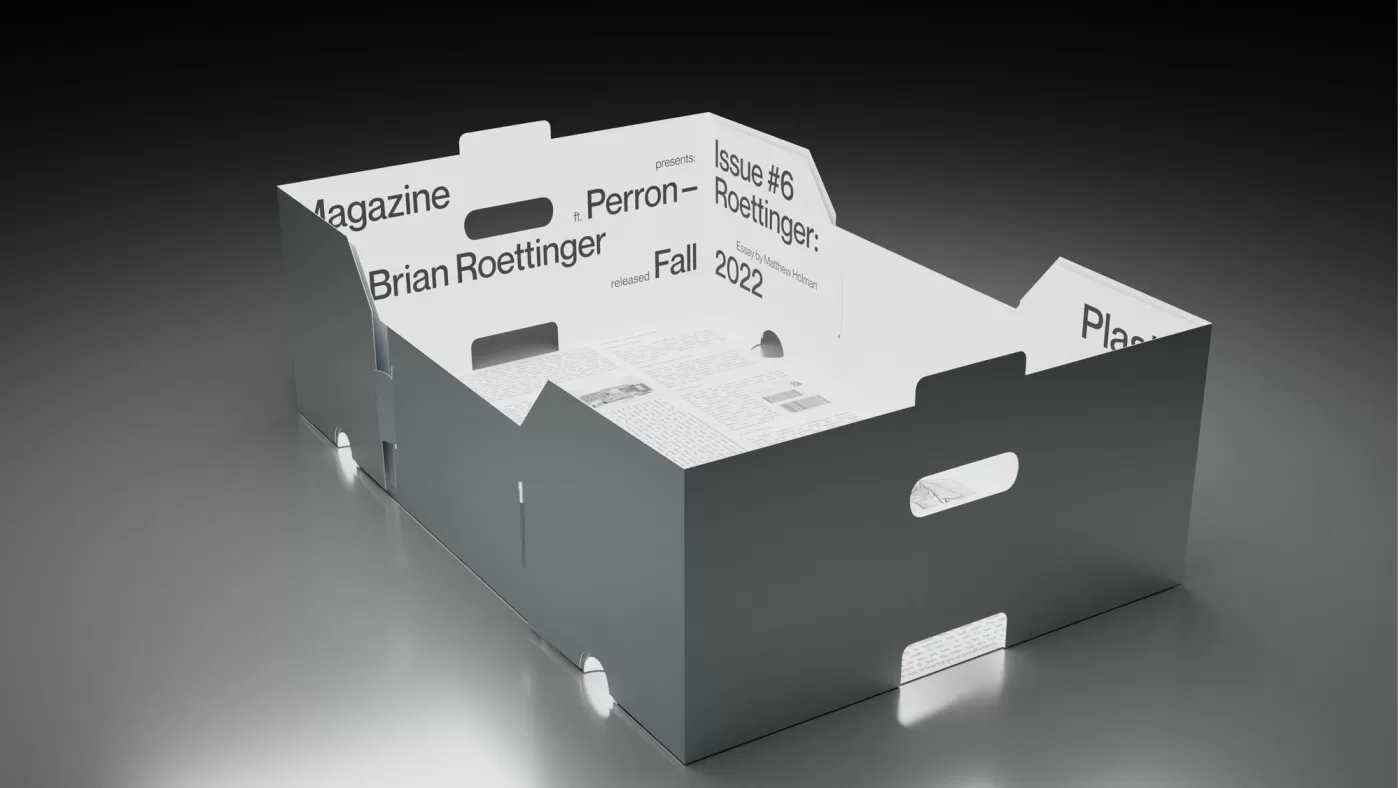

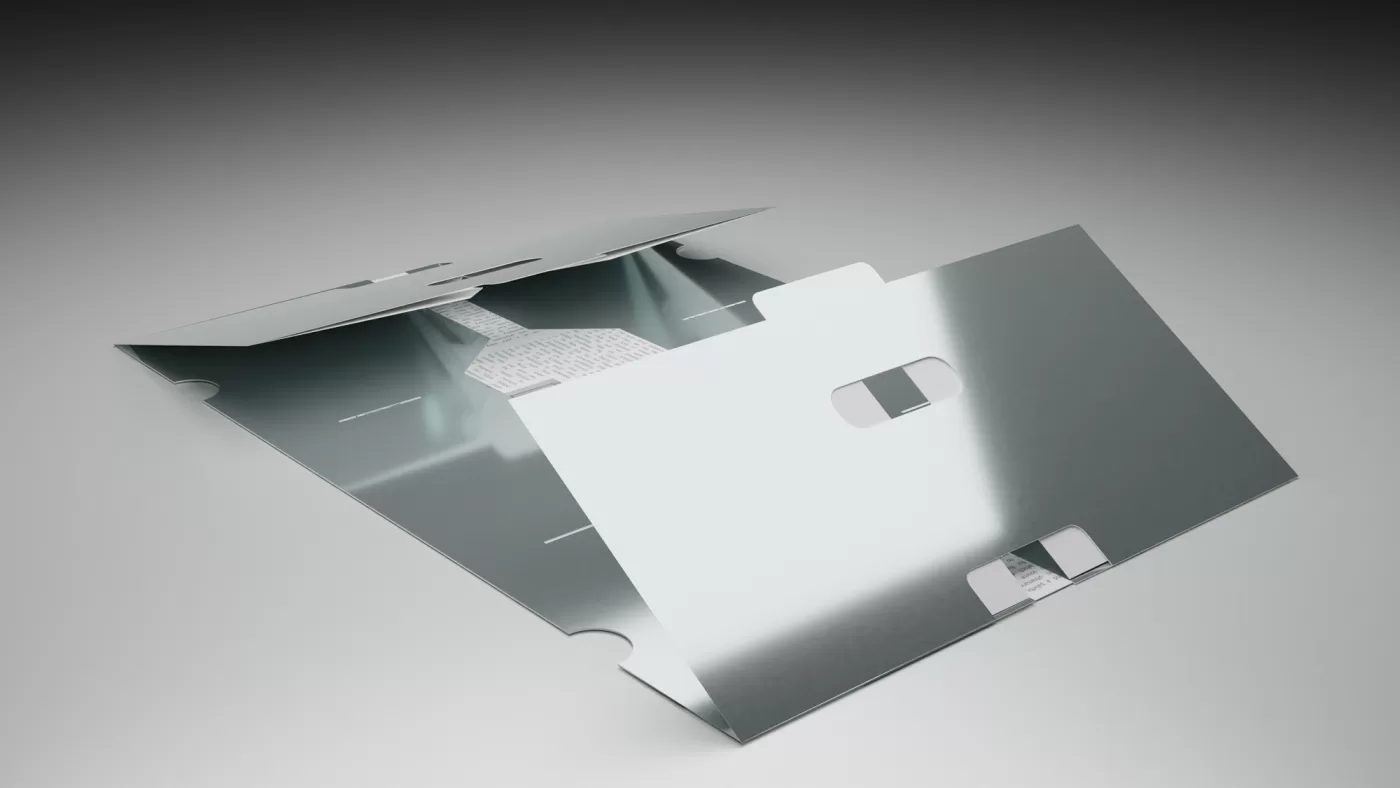

The box is still the best storage system. You can put anything in a box, but the box itself is also a subject. When we see a storage system, and I’m talking about any kind of storage system, a fruit box or an inter-governmental ballistic weapons storage facility, we are reminded of all the things that have been kept safe and transported and protected since the beginning. But something happened in the nineteenth century: we moved from a society of artisans to a society of industrialists, from the town to the city, and we had all these new objects to take care of and transport from centre to periphery and back again. The industrial contours and forms of this new world became its own visual language. The chrome box made by Perron-Roettinger for this issue speaks to this – in fact it’s the site of this text – and it’s visual subject is neither a colour nor a shade, but a reflector – like a mirror. Chrome coatings turn their back on you and look you in the eye at the same time. If we’re lucky we might see ourselves reflected, but they are also other-worldly and shimmer like red fairy dust on the surface of Mars. We hope that you find a use for this box, or else leave it flat and untouched and full of the possibilities of folding, but if after you’ve carefully assembled it using the die cuts and sores, we hope that you see yourself reflected.