The art world is a poisonous place

0 min read

When artists aren’t putting each other down they’re picking up pints, cigs and bags. The latest exhibition at London’s OHSH gallery asks why the art world is obssessed with self-destruction

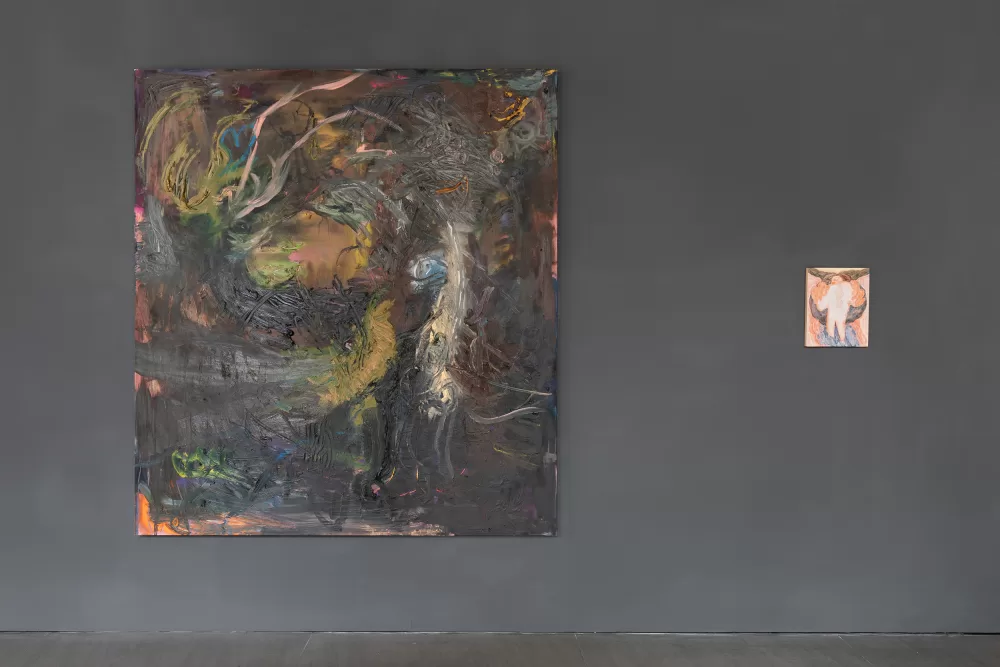

Benjamin Orlow, Ritual City, 2022. Photography by Benjamin Deakin. Courtesy OHSH Projects.

Artists and addicts often tell the same life story: youthful hedonism, growing dependency – desperation – and then, finally, either maturity and moderation or explosive self-destruction. The fact that there’s barely a Rizla paper between the world of art and that of narcotics is one explanation for this shared story. But that doesn’t explain why artists are infatuated, intoxicated, by self-destruction. Curators Sophia Olver and Henry Hussey of OHSH, London, are staging an intervention. Their exhibition ‘POISON’ gathers together the varied work of 16 contemporary artists to explore art and inebriation, and to ask if they’re inextricably linked.

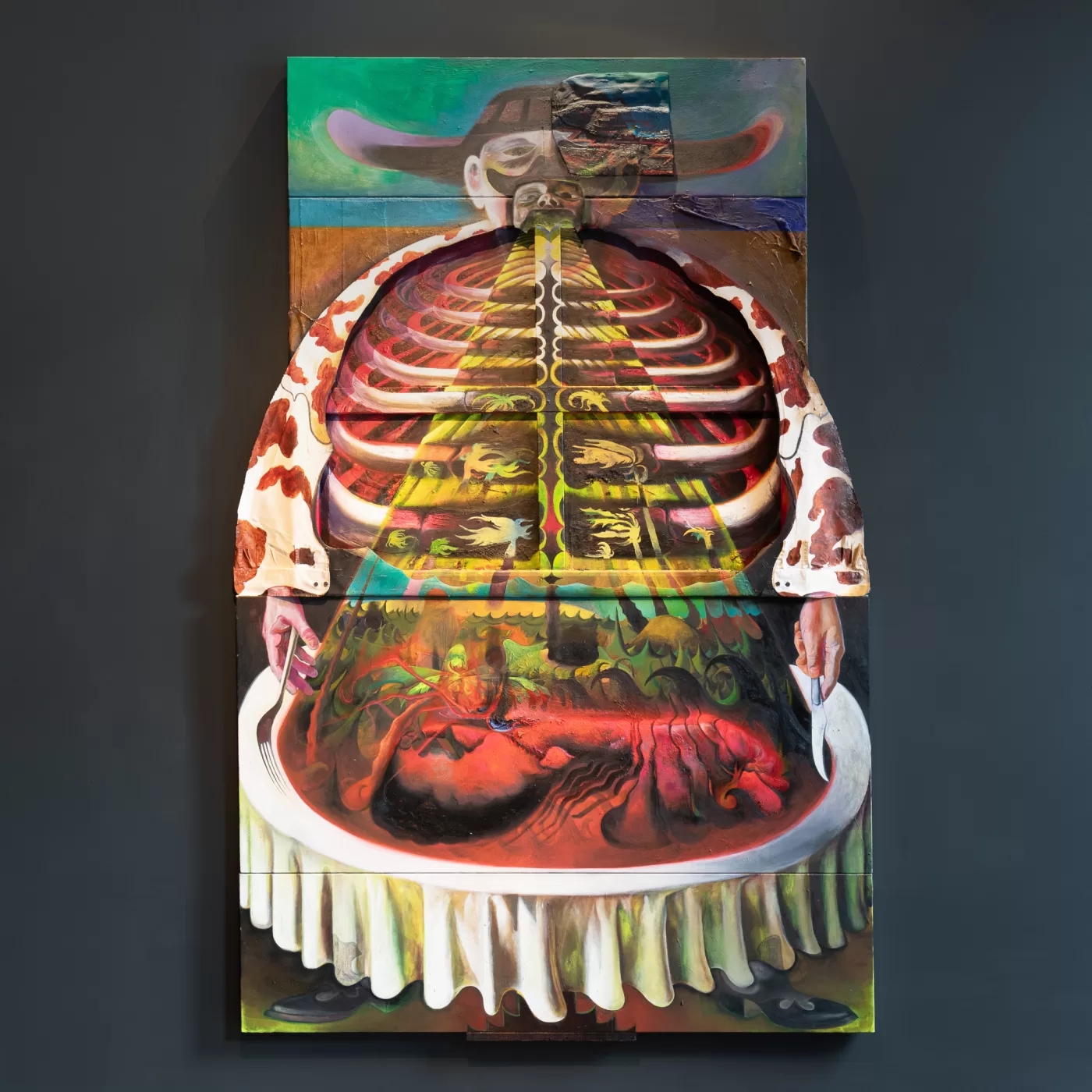

Intoxication is about releasing your inhibitions, at the best of times this brings joy: Lee Johnson shows a painting of a carefree guitar busker, standing on his head, pouring a bottle of wine from his feet to his mouth. The street is empty; he’s singing and strumming and drinking for no one but himself. But it can quickly turn to greed: Charlie Chesterman’s Dual Action presents a hallucinatory scene of gluttony; a man sitting with a knife and fork in hand, his innards spilling onto his dinner plate. Hung at the end of the room, it’s a reverential and revolting altarpiece to self-consumption.

Charlie Chesterman, Dual Action, 2023. Photography by Benjamin Deakin. Courtesy OHSH Projects.

Sometimes, it’s just the side effect of bringing people together: George Richardson focuses on the community and memory of English pubs by taking their furniture and fittings into gallery spaces. Here, he shows steam-warped snooker cues that seem to stand in for a huddle of auld lads bent double at the bar. Katie Surridge’s Jue draws on the ritual vessels used in ancient Chinese ancestor worship. She updates hers for the modern era, replacing the traditional offering of warm rice wine with a can of Stella Artois.

At its worst, it brings disgrace and mockery: a couple of small etchings by Campbell McConnell depict ‘sin-eaters’; desperate people who would sell their souls for a drink by taking on the sins of the dead in exchange for a mug of beer and a crust of bread. Benjamin Orlow’s oversized crumbling ceramic heads call back to the scrunched faces of Hogarth’s Gin Lane drunks and the ugly, expressive 17th-century ‘tronie’ portraits.

4 photos

View gallery

1 of 4

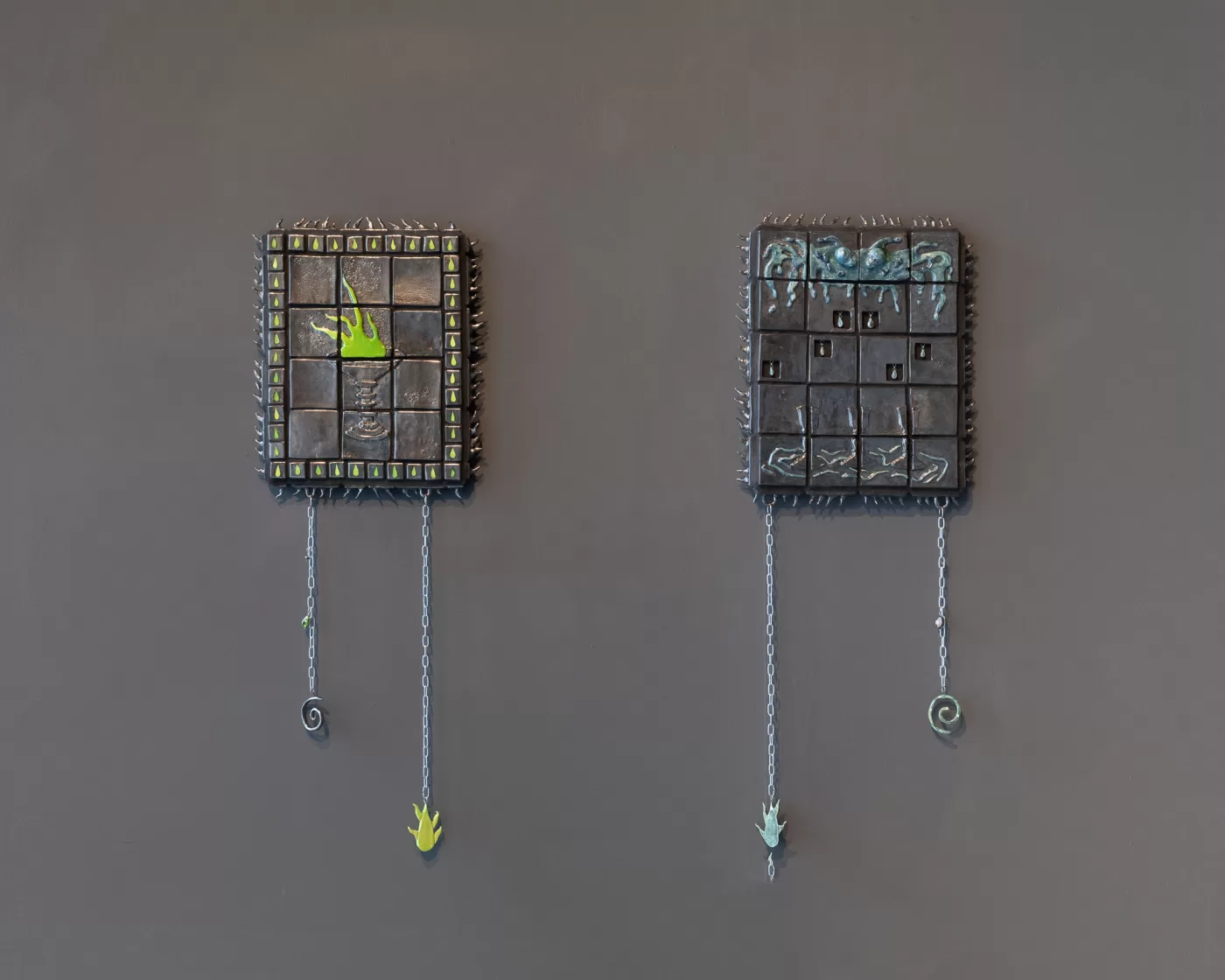

There’s two works, installations by David Cooper, that I kept returning to. They’re around human height. They’re built of metal armatures and rubber tube intestines and pieces of cast bronze and even clumps of human hair. They circulate liquid and they ooze and leak. They have to be topped up daily and (we all know people like this) they demand time and attention.

As I spent time with these works, I began to see why artists are drawn again and again to the subject of self-destruction. One reason is that art distances us from the consequences of our actions. We can sit back and comfort ourselves that our own bad habits (that extra drink, that extra cigarette) will never hurt us. That’s the selfish reason, at least. Another way of looking at it is that we care, deeply, about self-destructive people. Whether we acknowledge it or not, we all like to think that we could fix them.

David Cooper, 'Unconscious Drawing No.1', 2023. Photography by Benjamin Deakin. Courtesy OHSH Projects.

David Cooper, 'Unconscious Drawing No.2', 2023. Photography by Benjamin Deakin. Courtesy OHSH Projects.

Words:Jacob Wilson

‘POISON’ runs until 9th December at OHSH, 106 New Oxford Street, London, WC1A 1HB. www.ohshprojects.com