A quasi-holy experience with Mark Leckey

14 min read

In this interview, Mark Leckey returns to Alexandra Palace Park, where the Turner Prize-winner once had a spiritual awakening

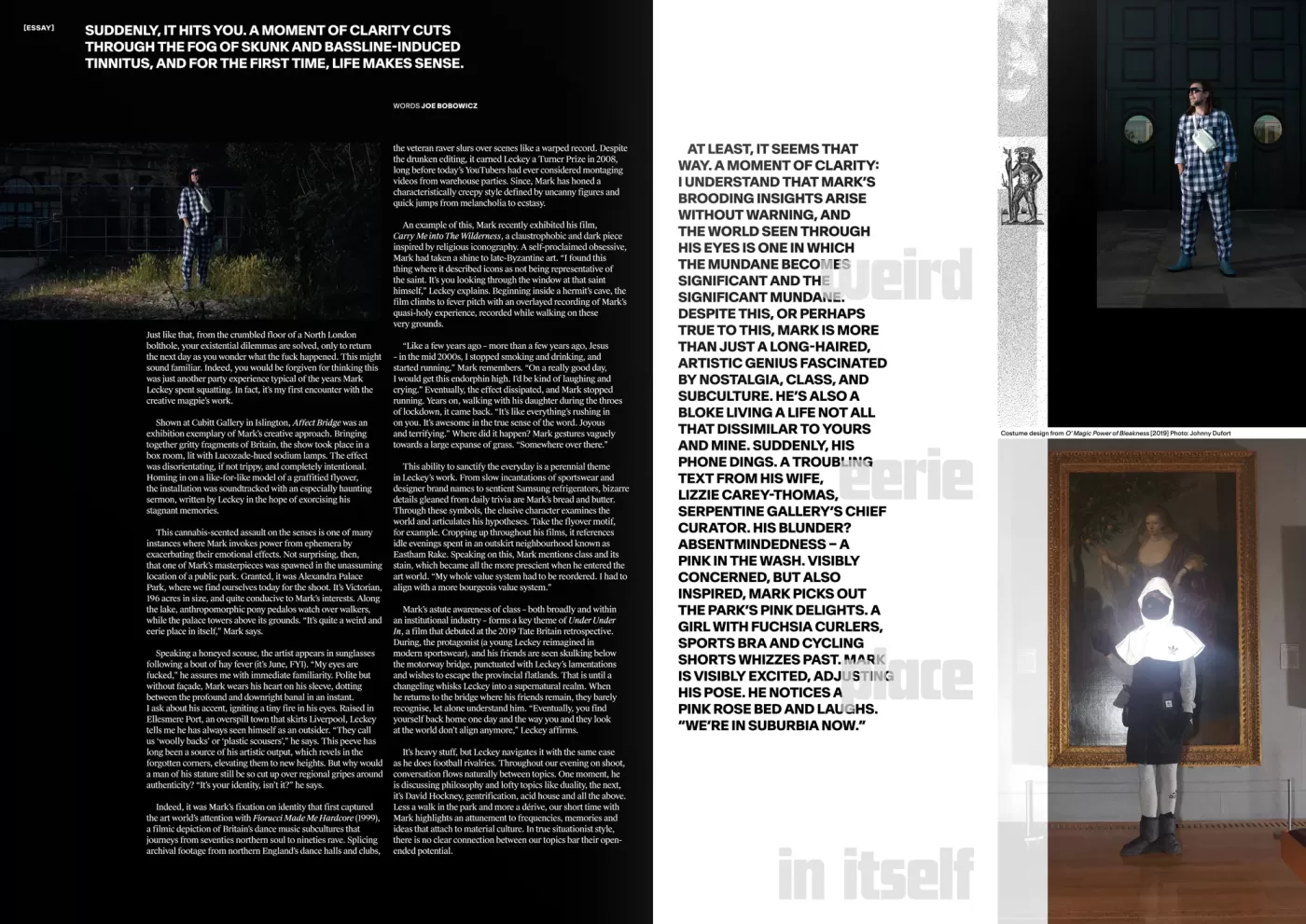

Spread from Plaster Issue no.8, dedicated to Mark Leckey

Suddenly, it hits you. A moment of clarity cuts through the fog of skunk and bassline-induced tinnitus, and for the first time, life makes sense. Just like that, from the crumbled floor of a North London bolthole, your existential dilemmas are solved, only to return the next day as you wonder what the fuck happened. This might sound familiar. Indeed, you would be forgiven for thinking this was just another party experience typical of the years Mark Leckey spent squatting. In fact, it’s my first encounter with the creative magpie’s work.

Shown at Cubitt Gallery in Islington, ‘Affect Bridge’ was an exhibition exemplary of Leckey’s creative approach. Bringing together gritty fragments of Britain, the show took place in a box room, lit with Lucozade-hued sodium lamps. The effect was disorientating, if not trippy, and completely intentional. Homing in on a like-for-like model of a graffitied flyover, the installation was soundtracked with an especially haunting sermon, written by Leckey in the hope of exorcising his stagnant memories.

This cannabis-scented assault on the senses is one of many instances where Leckey invokes power from ephemera by exacerbating their emotional effects. Not surprising, then, that one of Leckey’s masterpieces was spawned in the unassuming location of a public park. Granted, it was Alexandra Palace Park, where we find ourselves today for the shoot. It’s Victorian, 196 acres in size, and quite conducive to Leckey’s interests. Along the lake, anthropomorphic pony pedalos watch over walkers, while the palace towers above its grounds. “It’s quite a weird and eerie place in itself,” Leckey says.

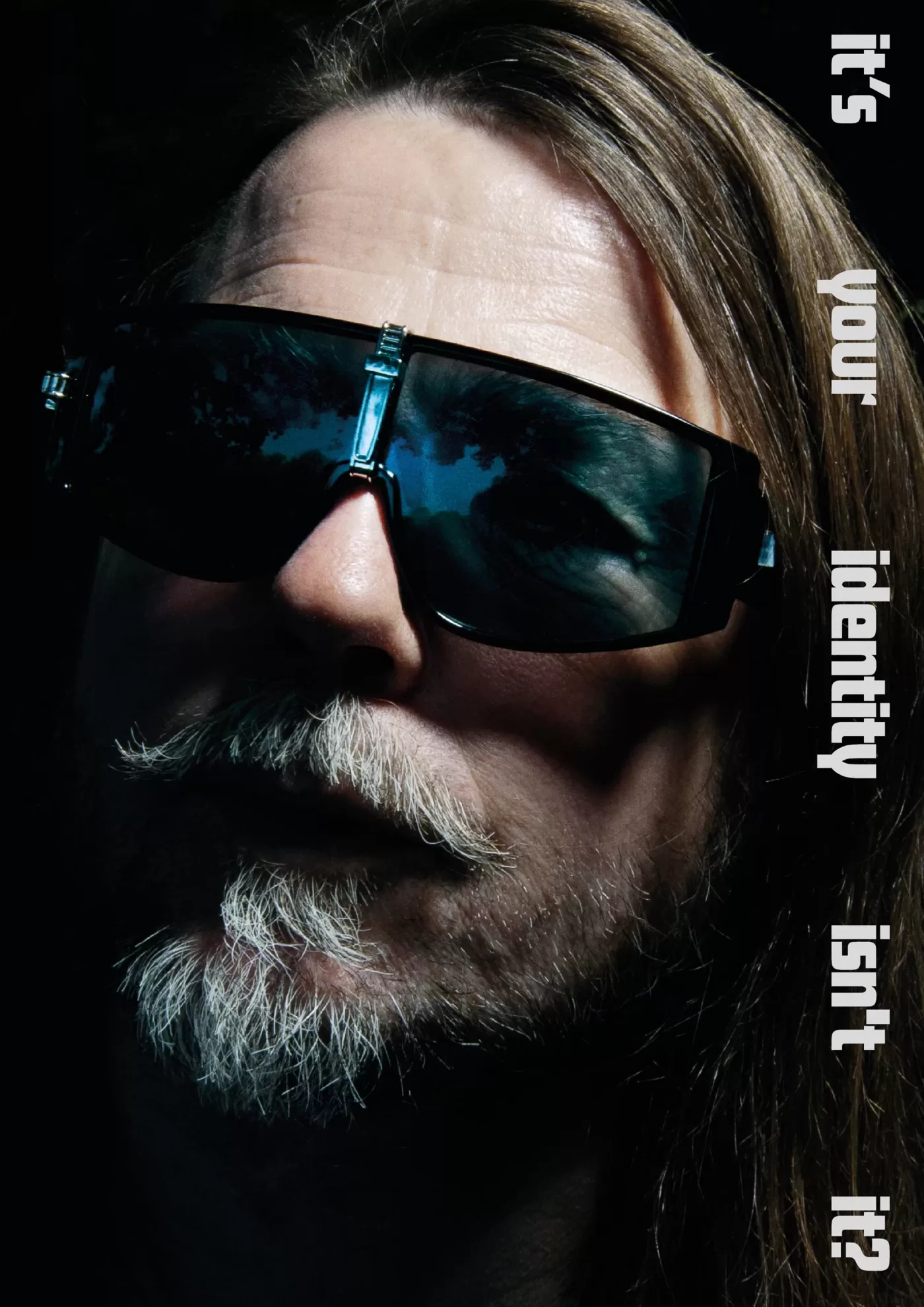

Mark Leckey photographed at Alexandra Palace Park, London

Speaking a honeyed scouse, the artist appears in sunglasses following a bout of hay fever (it’s June, FYI). “My eyes are fucked,” he assures me with immediate familiarity. Polite but without façade, Leckey wears his heart on his sleeve, dotting between the profound and downright banal in an instant. I ask about his accent, igniting a tiny fire in his eyes. Raised in Ellesmere Port, an overspill town that skirts Liverpool, Leckey tells me he has always seen himself as an outsider. “They call us ‘woolly backs’ or ‘plastic scousers’,” he says. This peeve has long been a source of his artistic output, which revels in the forgotten corners, elevating them to new heights. But why would a man of his stature still be so cut up over regional gripes around authenticity? “It’s your identity, isn’t it?” he says.

Indeed, it was Leckey’s fixation on identity that first captured the art world’s attention with Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999), a filmic depiction of Britain’s dance music subcultures that journeys from seventies northern soul to nineties rave. Splicing archival footage from northern England’s dance halls and clubs, the veteran raver slurs over scenes like a warped record. Despite the drunken editing, it earned Leckey a Turner Prize in 2008, long before today’s YouTubers had ever considered montaging videos from warehouse parties. Since then, he has honed a characteristically creepy style defined by uncanny figures and quick jumps from melancholia to ecstasy.

An example of this, Leckey recently exhibited his film, Carry Me into The Wilderness, a claustrophobic and dark piece inspired by religious iconography. A self-proclaimed obsessive, Leckey had taken a shine to late-Byzantine art. “I found this thing where it described icons as not being representative of the saint. It’s you looking through the window at that saint himself,” Leckey explains. Beginning inside a hermit’s cave, the film climbs to fever pitch with an overlayed recording of Leckey’s quasi-holy experience, recorded while walking on these very grounds.

“Like a few years ago – more than a few years ago, Jesus – in the mid-2000s, I stopped smoking and drinking, and started running,” Leckey remembers. “On a really good day, I would get this endorphin high. I’d be kind of laughing and crying.” Eventually, the effect dissipated, and Leckey stopped running. Years on, walking with his daughter during the throes of lockdown, it came back. “It’s like everything’s rushing in on you. It’s awesome in the true sense of the word. Joyous and terrifying.” Where did it happen? Leckey gestures vaguely towards a large expanse of grass. “Somewhere over there.”

This ability to sanctify the everyday is a perennial theme in Leckey’s work. From slow incantations of sportswear and designer brand names to sentient Samsung refrigerators, bizarre details gleaned from daily trivia are Leckey’s bread and butter. Through these symbols, the elusive character examines the world and articulates his hypotheses. Take the flyover motif, for example. Cropping up throughout his films, it references idle evenings spent in an outskirt neighbourhood known as Eastham Rake. Speaking on this, Leckey mentions class and its stain, which became all the more prescient when he entered the art world. “My whole value system had to be reordered. I had to align with a more bourgeois value system.”

Eventually, you find yourself back home one day and the way you and they look at the world don’t align anymore

Eventually, you find yourself back home one day and the way you and they look at the world don’t align anymore

Leckey’s astute awareness of class – both broadly and within an institutional industry – forms a key theme of Under Under In, a film that debuted at the 2019 Tate Britain retrospective. During, the protagonist (a young Leckey reimagined in modern sportswear), and his friends are seen skulking below the motorway bridge, punctuated with Leckey’s lamentations and wishes to escape the provincial flatlands. That is until a changeling whisks Leckey into a supernatural realm. When he returns to the bridge where his friends remain, they barely recognise, let alone understand him. “Eventually, you find yourself back home one day and the way you and they look at the world don’t align anymore,” Leckey affirms.

It’s heavy stuff, but Leckey navigates it with the same ease as he does football rivalries. Throughout our evening on shoot, conversation flows naturally between topics. One moment, he is discussing philosophy and lofty topics like duality, the next, it’s David Hockney, gentrification, acid house and all the above. Less a walk in the park and more a dérive, our short time with Leckey highlights an attunement to frequencies, memories and ideas that attach to material culture. In true situationist style, there is no clear connection between our topics bar their open-ended potential.

At least, it seems that way. A moment of clarity: I understand that Leckey’s brooding insights arise without warning, and the world seen through his eyes is one in which the mundane becomes significant and the significant mundane. Despite this, or perhaps true to this, Leckey is more than just a long-haired, artistic genius fascinated by nostalgia, class, and subculture. He’s also a bloke living a life, not all that dissimilar to yours and mine. Suddenly, his phone dings. A troubling text from his wife, Lizzie Carey-Thomas, Serpentine Gallery’s chief curator. His blunder? Absentmindedness – a pink in the wash. Visibly concerned, but also inspired, Leckey picks out the park’s pink delights. A girl with fuchsia curlers, sports bra and cycling shorts whizzes past. He is visibly excited, adjusting his pose. He notices a pink rose bed and laughs. “We’re in suburbia now.”

A month on from the shoot, Leckey sits down in his garden for a candid conversation over Zoom. The result is a hotchpotch interview-cum-catchup, clustered with nuggets of SoundCloud rap, West Ham lads, My Little Pony, and an earnest discussion of appropriation.

Joe Bobowicz: Last time we spoke, you mentioned your “dumping ground” hard drive and belief in the longtail theory, where niche interests coalesce online, potentially assembling in progressive moments. You’ve also started your Abundance Dump show on NTS radio. What’s the concept for this, and is it part of these ideas?

Mark Leckey: Yeah, I guess. I’ve been doing this slot on NTS for like six years and never given it a name. I started doing it casually, and then during lockdown, it was a lifeline. To be honest, I nicked that title. I saw someone put it on Twitter and thought, ‘Ah yeah, that’s good.’ In a way, it does connect to the longtail because there’s a bit where I talk about my interest in music, pop culture and trying to find the hidden and obscure, and there was something almost cultish about it at the extreme end. You would be continually looking for rarities, investing almost supernatural powers in them. When the Internet came along, it brought everything to the surface, making it available and visible. The whole dynamic changed. Now, it’s more like an abundance dump. They used to have the analogy of crate digging. Crate digging implies an archaeology; abundance dump seems more like it’s not worth much – trash, maybe. Which it isn’t. Maybe ‘abundance dump’ isn’t a good name. Maybe I’ve talked myself out of it!

JB: Are you a crate digger?

ML: I would never call myself a crate digger, but I definitely have that impulse. Going into a record shop and fingering through old LPs in a crate doesn’t appeal to me. I have the same sort of drive to find forgotten or obscure stuff. I have the mentality, but it’s more a knowledge that there is some weird and wonderful stuff out there, so I keep digging.

JB: That makes me think of your lecture/artwork, The Cinema in the Round, which features a lot of weird moments, from the CGI ship sinking in Titanic to that weird Simpsons episode, Homer 3D. Does that tie into this for you?

ML: Yeah, it’s about finding stuff. It’s funny you say that because I got scolded for the Titanic thing. With a lot of this, it’s basically appropriation. There’s sometimes a wilful ignorance with crate digging where you’ll dig out an obscure soul sample and not pay your respects or acknowledge the original musician. In this desire to find things [as if] they just magically appeared to you, you’re not considering their production. And I got caught with the Cinema in the Round. I had heard this idea of the Titanic being a sculpture that goes from horizontal to vertical, and obviously, I stored it in my crate. The person who had originally said it, Jerry Saltz, a New York critic, pulled me up about it, quite pissed off that I had nicked his line and not credited him.

JB: In the film for Cinema in the Round, you do credit him, though.

ML: Yeah, because I changed it. I felt bad. The thing is, at the beginning, in 2000, me and a friend of mine, Ed Baird, had an art band called Donatella and did mashups, singing over the top of other records. It was this idea of deliberately taking stuff – we used to talk about being poachers. That was fine because no one knew who I was. I didn’t have any gallery representation. But as I’ve become more successful, I have to be aware of not nicking stuff from… I’m happy to take stuff from above. It’s more taking stuff from below – it’s that idea of punching down.

JB: Is that partly because when you started out, you were signing on [for unemployment benefits], and now you’re in a very different situation?

ML: Exactly.

ML: Did you need to rethink it?

JB: I have. I don’t use as much found imagery as I used to. I had a record out during lockdown, and I used a meme for the cover. It was these West Ham football hooligans calling out Everton fans, but they looked ridiculous. The Everton fans mocked them, drawing on this image. I used that because it so accurately conjured up everything that I felt at that time about where I had come from, having two daughters and the world having this weird, digital, slightly magical realm. Anyway, it was irresistible. I tried to find out who made it and said publicly, ‘If you see this, just give me a shout, and I will offer you recompense.’

ML: It described how you were feeling and also your experience in the past?

JB: Yeah. It’s a photograph, originally, of four – I call them scallies, you call them road men – and they’re trying to look hard. Everyone mocked them by putting on the most ridiculous accessories – really girly things – feminising or sissifying them. It made a sympathetic image. I thought maybe that’s more like what boyhood is now. That aggressive, masculine energy I grew up with, it’s still there, but not as dominant. I liked that they were drawn with sort of unicorns – my oldest daughter is into that whole rainbow, unicorn aesthetic and those cartoon TV shows, My Little Pony and the rest of it. I have an ambivalence about it: I like it as an aesthetic, but it seems manipulative in how it colonises little kids’ imaginations. But maybe it’s like any attempt at branding when a corporation tries to exploit young kids; they find a way to make it theirs. You see that with My Little Pony. There are people who form close bonds around watching that programme, which is very long tail. In the long tail, it’s full of My Little Pony.

What are you listening to?

There’s a particular sort of trap: mumble, SoundCloudy… I love Young Thug and always looking for the more psychedelic end of that. I like it when it gets really fucked up. When they’ve been doing loads of molly and purple drank, and it gets all strange. I like early-seventies kraut prog-rock, too.

For example?

A German bank called Faust, I really like… Van de Graaff Generator, Tangerine Dream. And I follow a lot of music stuff on social media, so I pay a lot of visits to Bandcamp. If Boomkat put something out, I’ll listen to that. I like something murky that’s mixed so it’s echoey, reverby, pushed right back, with a smooth, almost R&B vocal. I keep listening to the Ghost Pop-Tape by Devon Hendryx. Klein… Stuff on the cusp of experimental and R&B is best. The song I’ve loved the most is by a British artist called LA Timpa. Because of NTS I am crate digging. This is the way you do it now: SoundCloud, YouTube, TikTok, wherever. I spend a lot of time digging around finding stuff.

Recently, you showed Dream English Kid in a show called Ancient Mews at Conditions, a gallery in Croydon’s Whitgift Centre, an old shopping mall. How did that come about?

It was these guys called Theo Ellison and Joe [Moss]. Conditions is a school in Croydon run by these two artists I’ve known for years, Matthew Noel-Tod and David Panos. They set up Conditions maybe four years ago and asked me to come in – this is pre-pandemic. I did a day’s teaching. It’s an alternative art school, basically. It’s grown a lot since I went. Then, I got this request from them, saying they wanted to show a video of mine. They gave me the show’s gist – so I said, ‘Oh, Dream English Kid’ is best. I liked this idea of ancient mews, and the ancient and the modern. I’m less likely to say no to an overly curated show in some well-known gallery, but if it’s just someone trying to do something, I can’t see a reason to say no. Most of my stuff is on YouTube. If I’m showing it there, what’s the difference?

The show you did recently at Pinacoteca Agnelli looked brilliant. Can you tell me about this?

This is the funny thing about the art world, isn’t it? There’s the show in an old Croydon shopping centre, and there’s showing a work with, basically, Italian royalty – the Fiat family. There is common ground, but they’re literally worlds apart. I got asked to do it. They had this incredible venue, the Lingotto, that was the Fiat factory. On top of the factory, famously it has this test racetrack. And it just sits there like a white elephant – they wanted to turn it into a public place. They’re modelling it slightly on the highline in New York: there’s this garden in the middle and they want public artwork throughout. They facilitated whatever I wanted and managed to hire a jumbotron screen, which is like an outside LED screen. It’s that end of the art world where I come away feeling slightly spoilt.

On our shoot, you got a text from your wife saying you’d dyed everything pink.

[Laughs] It was an enormous exaggeration. She has a white shirt that slightly, slightly changed colour. I didn’t feel at all bad when I saw it.